Herons having a Thames salmon supper. Photograph by Lisa Ann Wilson.

Six decades ago, London children used to leap from bridges into the Thames. They weren't being stalked by despair or by predators — they were just enjoying the summer thrills of a splash and a swim.

Nowadays, swimming in central London needs official permission from a Port of London Authority harbour master. Almost no one bothers them for it. People may pay fortunes for new luxury apartments by the river, but few want to actually dip in it. That might change. Architectural practice Studio Octopi has a plan called the Thames Baths Project, which, as the practice's Chris Romer-Lee says, is 'about re-introducing swimming into the Thames'. And he really means the Thames — not the chemically treated water of a normal swimming pool, but the river's actual, unfiltered water.

The Thames Tideway Tunnel is a sort of mega-metro line but for human waste rather than humans.

Before that can happen, the Thames needs to be cleaned up — again! In 1858, the river's Big Stink was so bad that Parliament hung lime-soaked sheets across its Westminster windows so as not to be overwhelmed, and then backed the brilliant engineer Joseph Bazalgette's massive plan for London's sewer system and treatment stations. Cholera was eliminated and the river breathed again . . . for a century anyway.

By the 1950s, industrialisation and growth had totally de-oxygenated the Thames. A massive sewer upgrade program brought river life back, including salmon and a thriving cormorant population. This century, London's growing again, and the sewers can't cope. Just two millimetres of rainfall can make them back up, unless the overflow is discharged. Currently, about 39 million tonnes discharges every year. That's why utility company Thames Water wants to build the Thames Tideway Tunnel, a new super-sewer mainly under the river. It's a sort of mega-metro line but for human waste rather than humans. When complete in 2023, the Thames should be faeces-free, and fit to swim in.

Thames Baths at Blackfriars Bridge — © Studio Octopi & Picture Plane.

A tunnel vent just by Blackfriars Bridge will create a plaza on the north side, and it is from here that the Thames Baths would be accessed. Studio Octopi have designed a complex structure on two levels, where different pools are accessed across boardwalks. All the pools are tidal and defined by gabion cages (rocks contained in metal baskets) that allow river water through, and provide a base for vegetation that creates different ecologies, planned by Jonathan Cook Landscape Architects.

The upper level, adjacent to the Embankment, is supported on piles and contains a kiddies' paddling pool and family pool, surrounded by salt marsh plantings and sedums. At low tide the river could be a few metres below the platform, so stored rainwater may be pumped into the upper pools, overflowing as a waterfall into a plunge pool on the lower level. An articulated ramp descends to this lower level, whose base is a concrete deck with cavities for buoyancy so that it rises and falls with the tide. More gabion boxes around it dampen the structure's bobbing up and down. The main pool is a regular three-lane rectangle, level with the river and bordering it with just a strip of reeds along its 25m length, while at its upstream end, river edge urban flora, particularly valerians, are to be planted. The plunge pool is a trapezoid. Romer-Lee describes the sequence of pools and the flows through them as 'kind of bringing the Amazon to the Thames!'

Plan of proposed Thames Baths, © Studio Octopi.

Of course, London already offers open-air swimming. There are the chlorinated pools of lidos like Tooting Bec, Parliament Hill and Brockwell Park, while the Serpentine and Hampstead Heath Ponds offers a wilder (though still artificial) environment that even attracts some swimmers in the depths of winter. But there's something different about the idea of swimming in an urban river. It connects to the very roots of the metropolis itself.

Most major cities owe their existence to rivers. They sprang up where the junction of land and water routes brought trade. The Dutch understood how water created city as late as the seventeenth century when they built Amsterdam's Canal Belt. But cities increasingly turned their backs to the waterfront. They built warehouses, walls, industry and roads that sealed the water off from city life. London went against the trend when it located the Festival of Britain by the river in 1951, but that was like a giant pop-up.

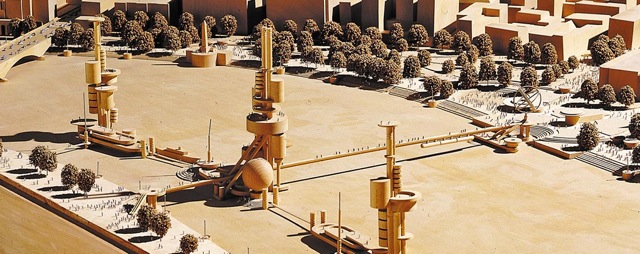

It wasn't until 1986 that the architect Richard Rogers recognised that the central role of the Thames needed to be permanently re-instated, in a vision called London As It Could Be. The Thames Baths is an idea directly following up that plan, under an ideas initiative involving the Architecture Foundation and the Royal Academy. And there's another inspiration as well — the seaside pools at Leça in Portugal, designed by Alvaro Siza, and opened in 1966, which brilliantly blur the ocean and the pool into a single experience.

Model of 'London As It Could Be', Richard Rogers' 1986 proposal, © RSHP.

Rogers had hoped that the state would refocus London along its river. To a certain extent it has, for example in the grand state project of the Millennium Dome (now the O2 Arena) which he designed, or the transformation of Bankside Power Station into the Tate Modern, immediately downstream from Blackfriars. But nowadays it's the developer who dominates the river's transformation. They too build big. The 'Boomerang' of One Blackfriars, a sculptural glass tower designed by Ian Simpson, for example, rises 163m and is under construction now, directly opposite the Thames Baths. Expect a subtle yet distinct conversation across the river between them, a counterplay of organic texture and the human scale to the latest Big Glass.

Swimming pools in the river are a trending twenty-first century urban phenomenon.

Internationally, swimming pools in the river are a trending twenty-first century urban phenomenon. Already, Copenhagen has its Harbour Pool, Paris the Piscine Josephine Baker and Berlin its Badeschiff, while New York has plans for a +POOL in the East River at Brooklyn. Even London has an alternative 'Thames Lido' proposal for the South Bank, designed by Lifschutz Davison Sandilands. But all of these are floating pools filled with filtered water. What's unique about Studio Octopi's Thames Baths is real river water. The only thing filtering the Thames at both its levels is those gabion boxes. They'll trap river debris and require maintenance — but as Romer-Lee says, that's not no different from dealing with 'the plasters, hair and verucca socks clogging up indoor pools!'

There's a long way to go before Thames Baths can become a reality. But fingers crossed; in the heart of the global metropolis, humanity is set to physically reconnect with the medium that made us an urban species in the first place: river water.

HERBERT WRIGHT is a London-based writer specialising in urbanism, architecture and art. He is Contributing Editor to UK architecture/design magazine Blueprint and contributor to others. Previously, he has written for magazines covering contemporary and twentieth century art, real estate, technology, and music. Recent work includes contributing to architectural encyclopedias for Phaidon, editing the London ICA website, and articles in journals in France, Mexico and Croatia. Herbert is the author of three non-fiction books about skyscrapers and urbanism.

Add new comment