Maracanã Stadium in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. World Cup 2014.

Ben Bryce recalls being in Buenos Aires during the World Cup in 2010 as the games were being played in South Africa. When Argentine games were broadcast Bryce said “you could have played your own soccer game on the widest streets of Buenos Aires. They were deserted.”

Tomorrow, the football-mad country of past great Diego Maradona and current incandescent superstar Lionel Messi will kick off against Germany in the World Cup final. Again, the streets of all Argentine cities will no doubt be vacated during the match.

Germany as an opponent is especially significant in complex ways for Argentines.

Representing ‘new’ world South America against an ‘old’ world European squad from Germany makes the Argentine team South America’s adopted favourites, perhaps even among disappointed Portuguese speaking Brazilians. Although Argentina and Brazil are great football rivals, Bryce claims, “I’m not sure Brazilians hate Argentina enough to support Germany.”

Less expectedly, Bryce, who teaches Latin American Studies at the University of Northern British Columbia, also believes having Germany as an opponent is especially significant in complex ways for Argentines.

German Argentines celebrating Oktoberfest in Villa General Belgrado. Photo credit.

In a 50-60 year period until the 1930s, approximately 100,000 Germans emigrated to Argentina, and after World War II, an additional 10,000 Germans arrived. Notoriously that group included at least a few prominent Nazis such as Adolf Eichmann (until he was kidnapped by the Israelis to face trial for war crimes) and for a time SS officer and Auschwitz physician Josef Mengele. And, one time Nazi party member Oskar Schindler, who saved Jews from perdition, also fled to Argentina.

The film is also to the Germans of my generation who dragged themselves out of the morass of guilt and self-hate.

So there’s no question that some of the post-1945 arrivals had links with the Nazi party, the German military, and even the killing machine of the Holocaust. However, as Bryce points out, the vast majority of German immigrants arrived before war broke out in 1939. Indeed, some 40,000 German Jews adopted Argentina as their home between the 1880s and the 1930s.

The frightening and sensational spectre of Nazis haunting Argentina in numbers is downplayed by experts like Bryce who correctly point out that most German immigrants had nothing whatsoever to do with National Socialism.

Nazi propoganda reached out to German settlers in Argentina.

However, that sad history still surfaces in popular culture. Just last year Argentine film maker Lucía Puenza released El medico alemán, a fictionalized account of Josef Mengele in 1960s Patagonia. In 2012 Argentine-German film maker Jeanine Meerapfel brought out El amigo alemán, about the friendship between an Argentine Jewish girl and an Argentine boy whose father has a Nazi past. Blogger Jutta Brendemühl quoted Meerapfel on her motivation: “This film is my declaration of love to Argentina, the country that welcomed my family into safety, but also to the Germans of my generation who dragged themselves out of the morass of guilt and self-hate.”

More weirdly, the popular 2011 English language film X Men: First Class features a Mengele-like character played by Kevin Bacon who flees to Argentina.

German immigration has influenced Argentine society and culture to a degree that might surprise those unfamiliar with the country. While the numbers are smaller than the much larger waves of Italian and Spanish immigration, Argentina has still been shaped by the German connection.

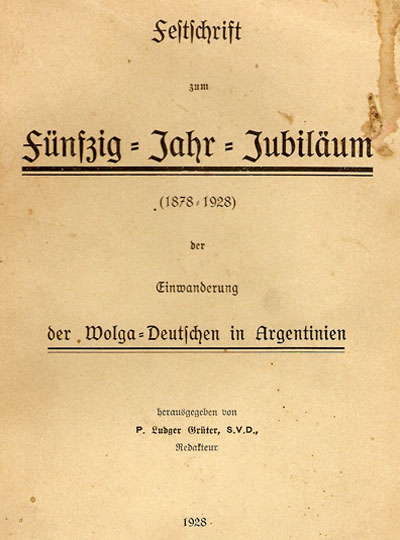

Book celebrating the 50th year of Volga German settlement in Argentina. Photo credit.

Some demographers claim that between 1.5 and 2 million Argentines today can claim some degree of German ancestry. Germany is a leading European trading partner and investor in Argentina. The German government actively supports German culture through the Goethe Institute in Buenos Aires, and still financially supports German language instruction and retention in Argentine schools.

There’s even a cheesy folkloric aspect of Argentine German culture as well. Some German farming villages — similar to Mennonite colonies on the Canadian prairies — have been transformed into touristy theme park getaways that urban Argentines and tourists clamour to visit.

The two great football rivals that will face each other tomorrow will share more than the pitch in Maracanã Stadium. The Argentine and German nations are closely associated through immigration, cultural and economic ties and the complex, sometimes bitter, tides of history.

JAMES CULLINGHAM, a contributing editor of The Journal of Wild Culture, is a professor of Journalism at Seneca College in Toronto and a documentary filmmaker. His most recent film is In Search of Blind Joe Death: The Saga of John Fahey, about the American guitarist and composer.

BENJAMIN BRYCE completed his dissertation “Making Ethnic Space: Education, Religion, and the German Language In Argentina and Canada, 1880-1930” in 2013.

Add new comment