It is being written with growing frequency that contemporary art (at least in certain circularities) is increasingly being produced with little or no reference to any semblance of a public. This is the ultimate Insider Art – the art that never leaves the white walls of the art school, art fair, collector’s vault, the art that never needs to. What, in this light, are we to make of the marked rise in prominence of that which is called Outsider Art?

Although its precise definition is much discussed – almost inevitability as soon as the term is raised – the broad conceptual shape of Outsider Art still stems from Jean Dubuffet’s 1950s definition of art brut as raw or uncooked and in direct opposition to what he termed “cultural art”. Art brut, and so Outsider Art by extension, is, for Dubuffet, “created from solitude and from pure and authentic creative impulses – where the worries of competition, acclaim and social promotion do not interfere”.

The apparent impurity that comes from any relationship with a public is immediately put to the test by Souzou, the Wellcome Collection’s brilliant new exhibition of Outsider Art from Japan. The exhibition opens with a series of works by Takanori Herai – loose pages double sided with markings and displayed both in vertical glass panels and bound together in book form. These graphic monochrome pencil-on-paper works initially appear completely abstract, but as the wall text explains (and as a short film at the conclusion of the exhibition explores in more detail) they are actually produced as a daily diary – detailing date, temperature and the artist’s name (incidentally reminiscent of AE Housman's monumentally dull diary entries – as seen in the British Library’s Writing Britain exhibition of 2012).

What is most intriguing is that this information is then carefully concealed by a process of systematic pencil shading. Concealed – but from whom? Family, friends, institutional carer, the visiting public, the art critic? We’re not told, but what is clear from Herai’s work is that a concept of an audience is structurally integral to the very concept of art – be it Insider or Outsider (just as a potential reader is always structurally integral to the writing of a diary – even if that reader is simply a future self).

Art always suggests, frames or enacts a possible breaching of the borders that it exists within.

What we have then is an immediate confrontation of the kind of issues that are inevitably raised by any public exhibition of Outsider Art. And what Wellcome does so well throughout is to avoid the usual pitfalls. So curator Shamita Sharmacharja has ensured that there is virtually no discussion of the biographies or illnesses of the artists whose work is on show, and no information at all about mental health or the institutions that treat them. It’s a very bold move for a place that is largely concerned with the public promotion of biomedical science. Or perhaps, it’s this status as a ‘non-art’ institution which allows Wellcome to be so refreshingly spare with the biography. Could, say, Tate Modern have done the same?

Either way, what this decision means is that the focus is on the art as cultural product – as art, whatever that might mean. And whilst about 70% of what’s on show is as garish and guileless as I’d kind of expected, that is no different to most exhibitions of professional contemporary art at the Tate, Hayward, ICA, Royal Academy’s Summer Show etc. Fortunately, what does interest me here is genuinely fascinating. From Noriko Tanaka’s rhythmically hypnotic embroidery to Shota Katsube’s amazing army of tiny warrior figurines – individually constructed from kitchen twist-ties; Kenichi Yamazaki’s painstakingly precise pen and compass graph-paper blueprints; Takuya Gamo’s fish and plant drawings, made up of strange little shapes – like viewing the world at a cellular level; and Hideaki Yoshikawa’s abstracted facial features – more like clay menhirs, simply cleft and adorned with rows of tiny, circular holes, like civilisation carved into a cliff-top.

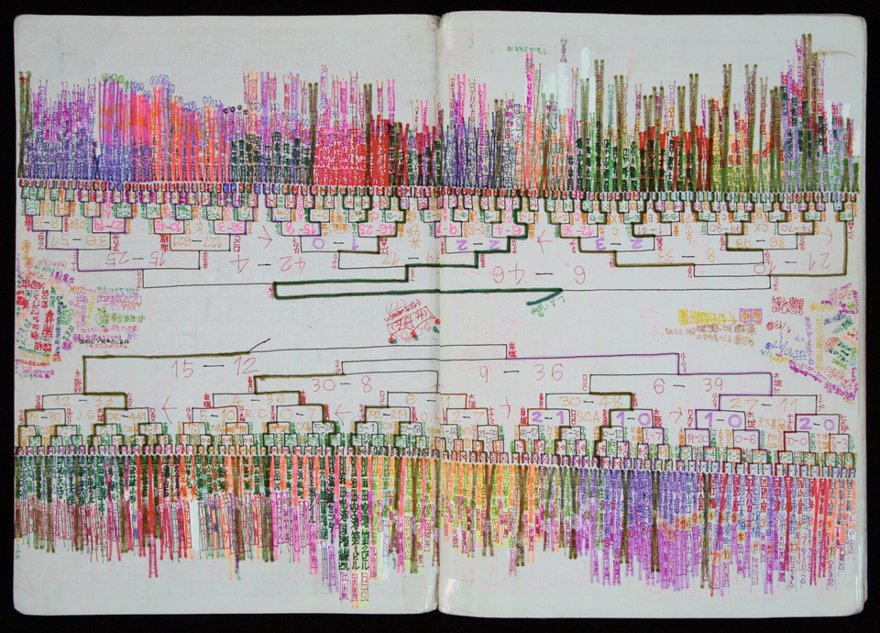

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the exhibition is the systematising impulse that runs throughout. The power of mapping comes through in Ryoko Koda’s strategic plans based on her own name, and especially in Norimitsu Kokubo’s monumentally imaginative cityscapes – one, still ongoing, will be ten metres long once completed. Elsewhere, this desire to create and impose meaning is especially evident in Shingo Ikeda’s baffling multi-coloured notebooks, Komei Bekki’s daily working ritual (the only note of biography allowed to creep in), and the evocatively literal titles of Takanari Nitta’s careful arrangements of amorphous shapes: 'Terrestrial Globe, Myself, Rabbit, Swallow, Horse, Glass, Beer, Cloud, Trousers, Sheep' is a favourite.

In the final room, a series of small-scale works by Koichiro Miya enact a conflation of methods of measurement as tools of both understanding and control. Music, time and the quantification of both intelligence and daily nutritional intake are layered upon each other in a regime of control and order, whilst a piano with 243 keys suggests a kind of over-reaching or over-running. In a sense, these little works might be a seen as a microcosm of the institutional delineation between Inside and Outside: without the delimiting strictures of order, there could be no meaning at all – but art (drawing; music; here a drawing of music) always suggests, frames or enacts a possible breaching of the borders that it exists within.

Souzou - Outsider Art from Japan is at the Wellcome Collection, London until 30th June 2013.

For a more in-depth exploration, read Rosie Jackson's Outsider Art: Where Did All the Outsdiers Go?

Image credit: Shingo Ikeda, Untitled

Add new comment