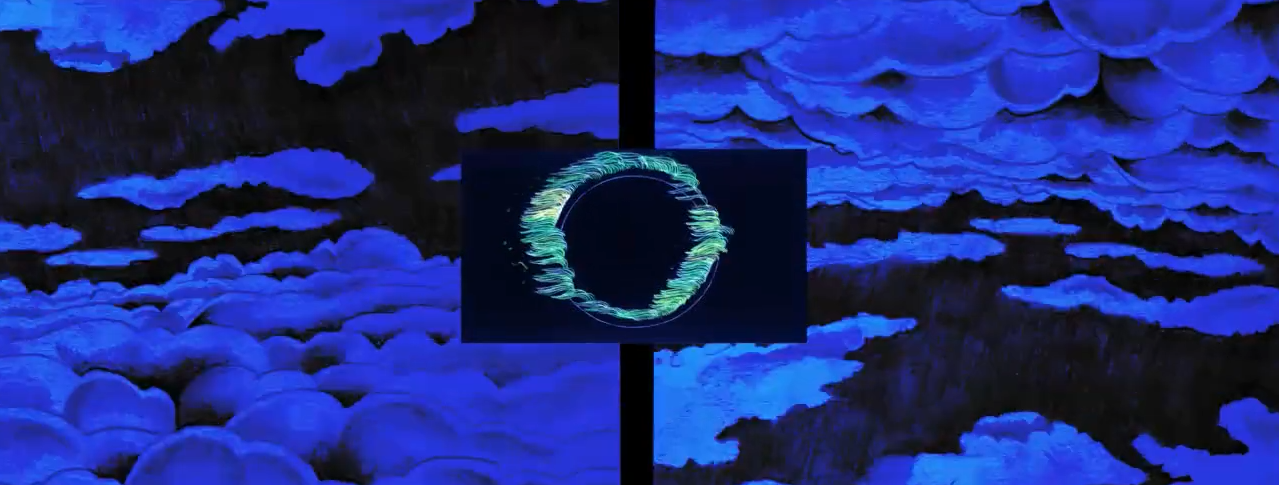

Works by WhiteFeather Hunter (left), OpenWorm (centre) in group exhibition Cultivars (Possible Worlds); real life bar (right)

Expanding Empathy

Cultivars (Possible Worlds) at Inter/Access

Cultivars (Possible Worlds) is a group exhibition at Inter/Access gallery in Toronto featuring work by four artists, Elisabeth Picard (Montréal), Stefan Herda (Toronto), Whitefeather Hunter (Montréal), and the open source, web-based, science collective Openworm. The exhibition ran from May 10-27, 2017, and took place alongside related Subtle Technologies programming, including an Open Studio and the hands-on workshop, “Solution Culture: Hydroponics for Creative Practice,” led by artist and environmental steward Paul Chartrand.

Curated by festival Artistic Director Zach Pearl, Cultivars (Possible Worlds) makes space for expanding conceptions of life. The works in the exhibition respond to questions that are at once ethical and aesthetic, political and ecological, such as: what is a life cycle? What constitutes a life, or a living being? These are questions that philosophers have long asked, with contemporary theorists like Judith Butler directing her feminist queer theory toward the admirable aim of “making more lives livable.” Today, as “the Anthropocene” becomes both an academic buzz-word and a renewed site of inquiry, philosophers and artists alike are left with the task of taking up questions related to life and livability with the perspectives and concerns of non-human agency and life: from animals to plants, bacteria, fungi, and other forms of organic — and even inorganic — matter.

This is a necessarily speculative project, one that we can press ourselves up against but that nevertheless remains bound within our own human body-brains, our own human use of language and representation. With the aims of ethics, empathy, experimentation, and a kind of empiricism in mind, the exhibition takes take up the challenge through contemporary art practices that work at the fore of digital and new media art, responsive environments, and bio art — or art in which living tissues, bacteria, organisms, and other biological processes form a part of the work. Often working between the laboratory and the studio, bio art artists face unique challenges and ethical dilemmas when they create work.

Given the urgency of ecological decline, does it make sense to have an art for art’s sake?

Montreal-based artist WhiteFeather Hunter’s practice is exemplary of some of the evocative moves being made in bio art — and feminist bio art — today. Bridging art and science in her work, WhiteFeather often engages with the processes and materials of fermentation when creating work, using bacteria and the symbiotic cultures of bacteria and yeast, or SCOBY, that forms the basis of the fermentation of sweet tea into the effervescent drinking tonic kombucha. Her recent work — developed in relation to her work with Concordia University’s Milieux Institute for Arts, Culture, and Technology where she works for the Speculative Life Lab, and as Coordinator for the Textiles and Materiality Research Cluster — fleshes out the lines dividing lab-based practices and feminism, science and witchcraft, and bio art and craft. Developing “biotextiles” out of living cell clusters, for example, and then bringing these biotextiles together with 3D printing technologies, Hunter’s exploration of materiality and tactility is deeply interesting for artists and researchers working across disciplines.

A feminist ethics and aesthetics of contemporary bio art practices emerge in WhiteFeather Hunter’s installation in Cultivars. Curator Pearl has brought together two separate but interrelated installations by WhiteFeather Hunter. In her single-channel video Pissed (blóm + blóð) (2016), created during a residency in northern Iceland, Hunter documents her process of using Indigenous Nordic techniques of urine fermentation of lichen to dye textiles. The ritual of using urine fermentation of lichen as a natural textile dye method is simultaneously scientific inquiry and self-sovereignty in the context of feminist bio art. Displayed next to the video projection is a shelf holding jars of the fermented-lichen dyes, and a wall-hanging textile which bears the traces of the different dyes. The resulting fibre work becomes a site at which the artist revisits her Nordic indigenous ancestry and “biogeographical data” through both bio art practices and “crafting” processes like weaving (Hunter).

Moving southward in the gallery, the viewer comes to Hunter’s second installation, entitled Aseptic Requiem (2014/16), a work that developed out of another residency that Hunter did, this time with the SymbioticA Centre for Excellence in Biological Arts in Western Australia. In Aseptic Requiem, the viewer kneels down on a textile work hand-woven by the artist, genuflecting before an “altar-like plinth” (Pearl) as the monitor gives a set of instructions on-screen alongside “digital microscopic video of 3T3 connective tissue cells” (Pearl). As mentioned, bio art practices present a unique set of ethical problems, including whether an artist should be using living materials to create artwork at all. With this work, the viewer quite literally meditates on human responsibility in bio art and science practices: specifically, the question of how to “compassionately dispose of in-vitro semi-living bio-organisms” (Hunter) that, when used in scientific experiments, are often “casually terminated” with little thought or feeling after use (Pearl). In place of such casual termination is a spiritualized ritual, in which laboratory directions are made both personal and sacred. WhiteFeather Hunter’s work makes space for meditative reverence within science practice, which curator Pearl, in his exhibition essay, eloquently describes as part of the show’s acknowledgment of our human responsibility “as world makers.” Hunter’s role as bio art practitioner positions her well in reflecting on these questions.

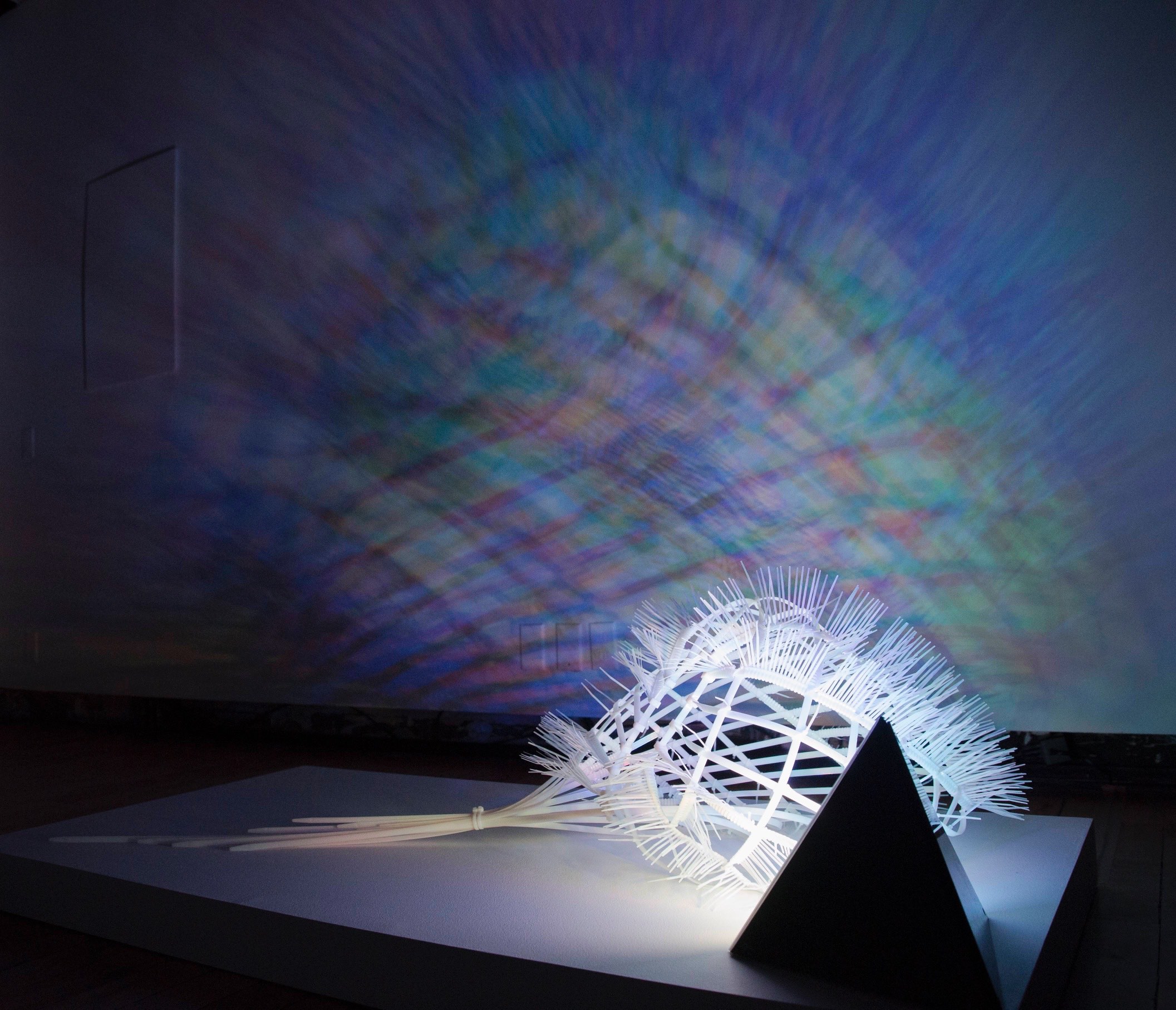

Elizabeth Picard's installation for Cultivars (Possible Worlds).

Cultivars (Possible Worlds) seems particularly interested in the possibilities that arise in the liminal space between “nature” and “culture”: whether it is Elisabeth Picard’s use of plastic zip-ties to create a responsive environment that mirrors the biomimicry of glow worms, or OpenWorm Foundation’s open source archive that maps the neural network of the roundworm in order to better understand the neural network of the human brain. The roundworm, often used in science as a lab-bound organism, takes on a new kind of digital life online. With OpenWorm, we are reminded of how the utilitarian imperatives of science and technological advancement present possible problems and possibilities when it comes to the place of contemporary art in society more broadly. Given the urgency of ecological decline, for example, does it make sense to have an art for art’s sake, or is it better advised, as Subtle Technologies seems to suggest, to have art directed toward particular aims — scientific, ethical, environmental? Pearl takes an active, enthusiastic role in educating his audiences about the scientific premises behind the various artworks: over the course of the opening reception, I learn about bioluminescence, and how both lichens and glow worms — repeating motifs in the exhibition — are bio-monitors whose deterioration signifies the presence of pollution and other interspecies hazards.

The exhibition brings together the use of naturally-occurring materials, like lichen (WhiteFeather Hunter’s Pissed) alongside unnatural, even latently toxic materials, such as cleaning agents (Stefan Herda’s Depression Flowers (2017)) and plexi and plastics (Elisabeth Picard’s glow worms) to create “unnatural” forms that are uncanny in their vague resemblance to living, sentient ones. As I look at Elisabeth Picard’s Pulsus, I see a giant dandelion of the sea: another viewer sees a cave. We’re like children looking up at the clouds, each seeing something different in these forms. Picard describes it as a fictional organism she has created through the use of plastic zip-ties and basketry techniques.

The discourse framing this show is very much indebted to object-oriented ontology and the contemporary theory strains of speculative materialism and speculative realism; I should disclose my own ambivalence around “OOO” — the acronym graduate students are likely to recognize as “object-oriented ontology” abbreviated — as I write this response. Even as I’m wary of the possibility, or even desirability, of knowing whether inorganic matter feels (in our human sense of feeling and emotionality), I understand its value as a kind of exercise in empathy. It is this latter application of OOO in which Pearl seems most interested.

While the exhibition strives toward more capacious conceptions of what it means to be alive and feeling, the show remains fairly ocular-centric and clean in its presentation. The works are predominantly visual, and in many ways the exhibition provides a space for us to bear witness to these different forms life through the act of viewing. Perhaps this is in part a critique of the empiricism of the scientific method, and the ways in which the ocular continues to be foregrounded as a way of knowing: Stefan Herda’s time lapse of mineral cultures in petri dishes in Crystal Garden (2017), for example, resembles an aestheticized view through a microscope. Indeed, the educational programs and workshops within the festival provide a counterbalance to this preference toward the visual with a more embodied experience of practices. This tendency toward the embodied is gestured to in Crystal Garden, as the minerals we look at with this kind of retinal distance are minerals essential to the functioning of our human bodies — herein is the kind of empathic-identification at the heart of the exhibition. There are some visually stunning resonances across the works in this exhibition that are conducive to speculative inquiry into the lines dividing nature and culture, reality and imagination, and human and non-human, and it is here that the exhibition really shines. In Cultivars (Possible Worlds), we reflect on the sanctity and beauty of life in its broadest terms—as inorganic, as barely sentient, as manufactured, as imagined — through our human eyes.

Emotional Ecologies

Universe in a Glass, co-presented by Subtle Technologies, the Toronto Animated Image Society (TAIS) and the Gardiner Museum.

I walk up to the top floor of the Gardiner museum and find a very polished looking room, the Terrace room, where the Universe in a Glass screening is taking place. I didn’t bring cash with me so I’m not able to try the kombucha cocktail; I’m slightly disappointed by this, even though as an experienced kombucha brewer I’m wary of the decision to mix kombucha with alcohol. I feel a bit out of place, under-dressed, not expecting the screening to be as polished as it is. I’m used to attending video art screenings in the basements of artist-run spaces: I’m taken aback by how beautiful the screening room is, and what a fine view we have looking out onto Queens Park, a central downtown green space adjoining the Ontario parliament buildings. At intermission, Subtle Technologies' Artistic Director Zach Pearl’s partner plays on the grand piano and I sit on my own thinking about space, drinking water, sustainability, and the future.

Just as the group exhibition of contemporary art Cultivars (Possible Worlds) takes up the multiplicities of life in unexpected or unacknowledged sites, the screening of animation films, Universe in a Glass, emphasizes the plurality of life within a single drop of ocean water. Time-based animations by nine emerging and mid-career artists become instigators for the audience's contemplation of the complex ecology of water — an ecology that is, as co-curators Ben Edelberg and Zach Pearl note, both technical and emotional.

Even as ecology and science are politicized today, art and animation provide different ways of being moved.

The intersection between art and science undergirds Subtle Technologies’s choice of screening partners: Jenn Snider, the Director of the Toronto Animated Image Society, emphasizes the science and math-based component of animation practice alongside the sculptural and drawing-based components when she introduces TAIS, while the current exhibition up at the Gardiner, “Janet Macpherson: A Canadian Bestiary,” takes up fragile ecologies from the perspective of sculpture.

The imperative of looking as a mode of understanding and empathizing with other life forms and ways of being that we find in the Inter/Access exhibition returns in Universe in a Glass, now homing in on water as a specific site of inquiry and reflection. Works in the screening range from abstractly formalist to educationally accessible, all converging around water and ecology. The first four videos (by David Buob, Kelly Zantingh, Kamiel Rongen, and Pedro Ferreira, respectively) consist of shapeshifting bodies and accumulating forms — the various states of water in its malleable materiality morph into different shapes and bodies: plant, animal, speculative. This fluidity of bodies, shapes, and forms continues through to the end of the screening — an entrancing motif that underscores the theme of interconnectivity central to notions of ecology broadly speaking. The screening concludes with Tara Dougans’s White Shadows (2015), developed during the Canadian artist’s residency in Berlin: it is a lovely, painterly video made in collaboration with musician Lydia Ainsworth. The vibrational pulse we find moving through the other animations comes to a climax here, with the synthesis of image and sound culminating in a playful and harmonious formalism characteristic of much of the animation in the program.

Tara Dougans. White Shadows, 2015. Still from the animated film shown at Universe in a Glass. Graphite, pencil crayon, acrylic, gouache on paper.

In Tess Martin’s Part of the Cycle (2013), the motif of water as a vibrational pulse comes together with a very interesting journey through the process of how water reaches people’s homes in the specific context of the Seattle area. I find Martin’s video to be particularly effective both as evocative environmental communication — necessary as this is in the age of climate change, and the increasingly polarized political climate in which “climate change” itself becomes ideological — and aesthetically as a work of animation. Indeed, the question swooshing through my mind as I watch these videos turns out to be a question that Pearl also had in mind, with him raising it to the artists during the Q&A session following the screening: what is the responsibility of the artist in uncertain times? In that moment, the Universe in a Glass screening became a microcosm for art-making more broadly: that some artists’s practices appeal to the emotions, others to the intellect, others to the spirit, some touching upon all three. During the Q&A with the artists who were in attendance, Dougans expresses her view of “the mind as an ecosystem,” in which “thoughts are the flora and fauna of the mind, prone to evolution.” As the artists respond to questions during the Q&A, it is clear that they share a common view: that even as ecology and science are politicized today, art and animation provide different points of connection for audiences, different ways of being moved.

Universe in a Glass takes place in the context of other exhibitions and conferences in Toronto that explore ideas related to water and pollution, and in this way demonstrates its relevance to conversations happening in the zeitgeist right now: from colloquia like “Muddied Waters: Decomposing the Anthropocene,” of which this writer was a co-organizer,” to Kelly Jazvac’s solo exhibition Proof of Performances opening at Gallery TPW this month (June 2017), in which the artist works with a team of women scientists to take up problems of plastics pollution and “forward contamination,” or the phenomenon of human acts of pollution on earth having polluting effects on other planets.

Image from the Subtle Technologies website: "...community building and knowledge sharing at the intersection of art, science and technology." [o]

Coda: Still Staying Curious

I leave the festival working through the various forms of colonization that persist in the present: the French and British colonization of Indigenous lands; the human colonization of the planet and non-human life in the Anthropocene; the colonizing projects of science and empiricism, toward noble ends. I’m relieved that Subtle Technologies responsibly foregrounds voices, perspectives, representations, and above all else the lives of Indigenous peoples, especially in light of the neo-colonial project that is Canada’s sesquicentennial.

I reflect on the sanctity of life in its broadest terms, and on the need to stay curious, to keep feeling, to be generous and to know when to take up space and when to give that space to others. I’m reminded of the responsibility of being a human in the world, and the necessity of cultivating ethical knowledge and practices as I walk through this life.

I find warmth in the small moments of reconciliation, and hope in the efforts toward sustainable and ethical communities and ecosystems.

NOTES

“Intimately linked with notions of witchcraft, in its emphasis on radical bodily materiality, informal knowledge production and even potion-making, (such as through stirring noxious fluids in a heated cauldron in order to extract the magicolour transformation inherent in rare herbs), natural dye methods such as those done via urine ‘fermentation’ fall within small-scale and thus ethical production and use of resources, also linked to feminist perspectives on labour.” (Artist statement, WhiteFeather Hunter.)

“According to a study published by the Census of Marine Life in 2010, it is estimated that there are over 1 million living cells per millilitre of seawater.” (Curatorial statement for Universe in a Glass, “Water, Water Everywhere” by Ben Edelberg and Zach Pearl.)

READ Part 1 of this series, "At Subtle Technologies 20'.

LAUREN FOURNIER is a writer, curator, artist and researcher. She is currently a doctoral candidate at York University in Toronto, where she is completing a cross-disciplinary study of “auto-theory” as a contemporary mode of feminist practice across media. She is the editor of a new anthology of critical writings, Fermenting Feminism (Laboratory for Aesthetics and Ecology, 2017). She lives in Toronto. ~ laurenfournier.net

Add new comment