MY CHILDHOOD was rich in amphibians and reptiles. One of my earliest memories is of catching a tree frog and feeling it pee in my hand. I spent one summer rescuing frogs and toads from a defunct swimming pool. There seemed to be an endless supply willing to fall or jump into the rainwater-filled pool, but unable to hop out again without my help. It was also common to see garden snakes sunning themselves in the road or slithering harmlessly through the grass. Salamanders were liable to be found under most any rock a child would care to look for them, and legions of box turtles roamed the Maryland countryside, leaving me their sun-bleached shells when they were done with them.

I created a makeshift terrarium for him in a cardboard box, placed the box on the stove and turned on the warming lights to see if he would bask.

My family moved around a lot when I was a child. When I was ten, we stayed for a few months in Newtown Square, PA, while waiting for our house in Maryland to be ready after coming back unexpectedly early from Germany. There was a decrepit rainwater- and leaf-filled swimming pool in the backyard, and a pond not far away from that — so, the perfect set-up for frogs to hop over and become trapped. I would stand on the edge of the pool deck and catch some of them with a net, and climb down into the muck to grab the more difficult cases. One of my favorite pictures of myself is from that summer: I’m wearing a filthy bathing suit and a goofy grin and holding a giant bullfrog I’d caught. Other sorts of critters would fall into the pool too, not just frogs. Some animals died before I found them; I have a rather vivid memory of a drowned vole. Looking back, it seems like the adults should have used a pool cover to prevent these tragedies from happening.

In my adult life, there have been fewer encounters of the froggy kind, and up until recently, I hadn't seen a salamander, snake, or turtle in the wild in many years. Part of it may be that, as a grown-up, I’m not as close to the land. I don’t regularly have my hands in dirt or water. Amphibian and reptile populations are also dwindling more than other types of animals, as an effect of pollution, habitat destruction, depletion of the ozone layer, and climate change. The storied canary in the coal mine may in fact slither or hop rather than fly.

"He turned out to be an Eastern Painted Turtle, so I named him Vermeer." [o]

But in May, a colorful little turtle crossed in front of my car in the middle of a vast parking lot at an outlet mall, apparently doing his best to become roadkill. I took him home to figure out what species he was and where he belonged. He turned out to be an Eastern Painted Turtle, so I named him Vermeer. I created a makeshift terrarium for Vermeer in a cardboard box, placed the box on the stove and turned on the warming lights to see if he would bask. He obliged. But he wouldn’t eat anything I offered: orange sections, strawberry, lettuce, and, at the Internet’s behest, a live ant. The ant climbed onto Vermeer’s head as he submerged under the water in his mixing bowl swimming pool. I regretted being responsible for anticide in the name of turtle welfare.

Vermeer started coming over to the side of the box when he heard my voice. He had more personality than I would have expected. I thought of keeping him as a pet, but I already had an elderly dog and shared custody of a parrot, both of whom would have objected strenuously to my attention being divided three ways.

So, after much online research, hand-wringing, requests for advice, and surveying of the area with Google Earth, I released Vermeer the following day at a pond a few hundred yards from where I found him. I had misgivings because the pond is surrounded by roads, and Vermeer might go exploring again ("he" may have been a female looking for a place on land to lay eggs). Yet, it did look like a habitable spot: There were ducks with their ducklings and a marshy area with lots of bugs. I placed Vermeer at the water's edge and he swam leisurely towards the center of the pond, surfacing every few yards until I couldn't make him out anymore.

The common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina). [o]

A couple of weeks later, while driving home from work, I found a hefty dinosaur of a turtle in the right lane of Route 40. The wildlife rescue leagues advise people to set a turtle on the other side of the road "where it was headed", but this one was marching straight down the highway. There were only stores and parking lots on either side. I pulled over, put my hazard lights on, picked up the turtle with both hands, and put him in the passenger seat.

He opened his impressive jaws at me when I first picked him up, but other than that he was one laid-back reptile. He sat in the same spot all the way home, and then sat some more in the box I put him in while my family ate dinner. Vermeer had been very active, so I worried this turtle was ill. I didn't want to stress him further him by keeping him overnight, so with more swift decisiveness (but still quite a bit of hand-wringing), I drove to the local watershed and re-homed him in a marshy pond a ten minute human hike from any road. It was near sunset, and the frogs around the pond were singing.

When I placed Kerouac (I named him that because I found him on the road) the Eastern Snapping Turtle near the water, he sat there staring at a fixed point in the distance with his prehistoric eyes. I pushed on the back of his shell to get him moving, but he resisted, so I picked him up and placed him right at the water's edge with his chin in the water. Swimming all around were the tadpoles and polliwogs whose progress I'd been tracking each time I hiked there with my dog. He wasn't interested.

Still, I worried. This can't be where he’s from, I thought, given how far away we are from where I found him.

Again I wondered if he was ill. Shouldn't he want to escape from me, his captor and potential predator? Perhaps I should take him to a wildlife rehabber. I pulled my phone out to call for advice, but had no cell service this far out in the woods. As I was putting my phone away, Kerouac moved into the water. He used his thick, muscular legs to dive deep and swim out of sight.

I smiled to see him physically strong after all, but still, I worried. This can't be where he’s from, I thought, given how far away we are from where I found him. How dangerous is it for him to be released in unfamiliar territory? At least he's not going to be run over by a car. But what if there aren't any other snapping turtles here and he doesn't get to mate? What if he tries to go home, wherever that is? What if . . . well, there is no what if. He will be eating some frogs if he survives (so by being a turtle rescuer, I am a frog killer by proxy).

That evening, I tried to discuss these issues with my mother the retired biologist. She reminded me that the vast majority of tadpoles are going to die anyway, and seemed unmoved by the plight of a particular animal. But I am not scientific enough to view animals as interchangeable members of their species. This is my turtle. These are my polliwogs. They crossed my path and I feel responsible for them. I can’t leave an animal where it is if it appears to be in danger, even though I know that I may not be able to change the overall amount of suffering by trying to help.

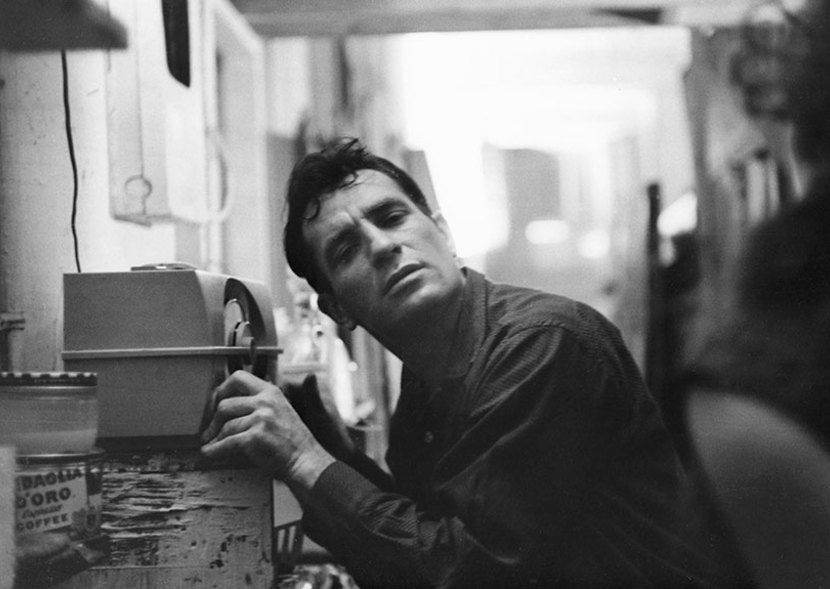

"I named him that because I found him on the road." Jack Kerouac leans closer to a radio to hear himself on a broadcast, 1959. (John Cohen/Getty Images)

Although I’m usually inclined to view the universe as chaotic, I wondered whether there was some sort of synchronicity at work here. A couple of my hippie-er acquaintances surmised that mother nature must be trying to send me a message by placing two turtles in my path in quick succession after I’d led a turtle-less existence for so many years. What the heck. It’s possible. Perhaps turtles are my spirit animals, as someone suggested. Maybe I am being told to slow down and enjoy life more. Or maybe I’m being shown that I can’t actually affect the balance of pain and joy in the world, and that I shouldn’t try. Or maybe I’m witnessing a miraculous resurgence of turtles in my geographical area. Or maybe I’m falling victim to the human tendency to see patterns where none exist.

Anyway, Universe, I’m not sure what to do with your turtles. If you want to give me more turtles, that's fine. I'll likely perform the same rescuing/hand-wringing/releasing/worrying act as before. If I’m in the midst of your Turtle Test, I don’t yet know how to pass it. If there's a message, I'm not sure I've received it.

Third time's the charm? ō

CYNTHIA LEWIS is a writer whose work has appeared in journals such as flashquake, Writer's Choice, and Little Brown Poetry. She won the Janice E. Cole Writing Prize as a student at Hood College and was a nonfiction finalist in the Arts & Letters Journal contest. She lives in Frederick, Maryland.

Add new comment