Down the steps of Stave Hill.

MOUNT LONDON: ASCENTS IN THE VERTICAL CITY

Tom Chivers & Martin Kratz (editors).

Penned in the Margins, London.

216 pages, hardback. £10.

How does a city come to be? What was it made from? Why is it where it is?

Mount London, a new book by independent publisher Penned in the Margins, uses the clever premise of examining the much considered urban geography of London from 25 elevated vantage points. As a collection of essays by writers, poets and urban cartographers with an interest in landscape, space and place, the book is a catalyst for assessing a city that can mean so many different things to different people. Each writer stands atop one of these 25 ‘peaks’ — from the lesser hills of Stamford Hill (36m) to Crystal Palace (112m), to 'ghost hills' in the back streets and a descent into the deepest part of the Tube — to explore ‘not only the physical topography, but also the psychological experience of urban hill walking.’

Battersea Power Station, 1930s.

One of the 23 essayists had travelled as a child by coach from her native Derbyshire. Running up Parliament Hill, she received her first glimpse of the much fabled capital city. To another, it was a mid 1990's prevalence of inequality; the rose-tint of Notting Hill formed a vivid contrast against a young Nigerian boys efforts to integrate into a new home hindered by crude racial stereotypes. Another shares an account of commuters momentarily drawn to the window of a train as is passes the majestic proportions of Battersea Power Station. The passengers were in a trance like state as the carriage rocked from side to side, but this impressive building brought them back to consciousness.

If this book’s desire is to guide those that read it to open their eyes wider and listen more intently to understand where they are, then it is a success. Any new resident within a London borough is strongly recommended to read it.

Amidst the huge assortment of books about this city as a place, Mount London is uniquely akin to a quiet stroll through Hampstead Heath — a much crafted opportunity to appreciate the small joys of a vast city.

LIST OF AUTHORS: Matt D. Brown, Sarah Butler, Tom Chivers, Liz Cookman, David Cooper, Tim Cresswell, Alan Cunningham, Joe Dunthorne, Inua Ellams, Katy Evans-Bush, SJ Fowler, Bradley L. Garrett, Edmund Hardy, Justin Hopper, Martin Kratz, Amber Massie-Blomfield, Karen McCarthy Woolf, Helen Mort, Mary Paterson, Gareth E. Rees, Gemma Seltzer, Chrissy Williams, Tamar Yoseloff.

EXCERPT FROM MOUNT LONDON

Stave Hill, Rotherhithe — by Tom Chivers

A peninsula is a dead end. Take the single-decker C10 from Bermondsey and see how quickly the city thins out the further in you get: the solid, busy matter of streets and offices and people dissipates along the snaking path of Rotherhithe Street. It is impossible to believe there is anything further east until the bus shifts back onto the Lower Road to Deptford. Visually, Rotherhithe is caught between the Shard to the west and, across the bend in the river to the east, the looming pyramids of Canary Wharf. This alignment with the city's two highest points serves only to strengthen our sense of the peninsula as flatland, an urban tabula rasa.

With no hills of its own, the only option for Rotherhithe was to build one. From the tip of the peninsula — its most northern point — we turn off the main road and head south into the heart of the peninsula, passing first Mellish Sports Ground and then Bacon's College — alma mater of boxer David Haye and Big Brother contestant Jade Goody. Lagado Mews becomes Timber Pond Road. The atmospherics of the Rotherhithe interior are so uniformly suburban we could be in the outskirts of any small town in the south of England. Only the sporadic sight of the Gherkin or One Canada Square peeping over a retaining wall or emerging at distance through plane trees reminds us where we are. Reaching the suggestively-named Dock Hill Avenue, we see the Hill for the first time, at the apex of a dead-straight, tree-lined footpath, its perfect symmetry framed by a sky now wiped clean of cloud.

The only major feature we cannot see is the Thames herself, obscured by all the buildings hustling in on her banks. Great slug of river. Strong brown god.

Stave Hill is a thirty feet-high grass mound in the shape of a truncated cone (or frustrum). Its form is suggestive of the Command Module of a space rocket that, having re-entered the earth's atmosphere, has crash-landed unnoticed in SE16. To climb this Hill is to participate in a ritual ascension. The approach seems designed to echo the geometric avenues of Avebury; a sloping path marked at regular intervals by large rectangular structures swamped in ivy — ruined megaliths that loom above the joggers and dog walkers. The Hill itself is a kind of miniature of the prehistoric chalk mound at Silbury, Wiltshire. The grass is luminous, as if it has been dowsed in glow-in-the-dark green paint. I almost expect Bilbo Baggins — or the Teletubbies — to emerge from a trapdoor in its flank.

View from Stave Hill at night. [o]

Stave Hill's skin may be turfy, but its innards are all rubble and waste. Just like the mounds of Arnold Circus (2.3 miles Northwest) and Northala Fields (14.5 miles Northwest by west), the Hill is a glorified slag heap; constructed in 1985 using the spoil from the dismantling of Stave and Russia Docks. As we ascend the concrete stairway that reaches up the face of the mound in the manner of a Mayan pyramid, I am thinking of a set of black and white photographs of the Surrey Docks taken by my friend Bill Pearson in the early 1980s. A Cumbrian émigré, Bill ended up in south-east London and became a compulsive walker and chronicler of an industrial landscape on the cusp of ruin and renewal. In one photograph, local children are swimming in an abandoned dock basin, metres from a curdled mass of floating junk. In another, a grotesque still life, what looks like the disarticulated bow of a cargo barge lies tits-up on an empty dockside, with two stilled rig cranes for company.

Stave Hill is a memorial to this disappeared world. It is also, quite literally, made of it. Perhaps, then, it is more like a cairn: a gathering of local materials into a waymarker or ritual node. Nothing new.

Beneath the skin of this place lies a forgotten history of labour — of stevedores and deal porters testing their strength and skill against steel and timber.

Nothing alien. Nothing that cannot be collected from the immediate environment and redeployed. Stave Hill is as good a symbol of London than any: an entire city built on the accumulated rubble of its past.

The summit of the Hill is flat, concrete and wind-blown. The views over the city are staggering. I survey the skyscrapers of the Square Mile several miles away to the north-west, the Shard stabbing knife-like into the sky. The turrets of Tower Bridge and the London Eye are like children's toys, absurdly miniature. The towers of Canary Wharf rise up in front of us so close you feel you could reach right in. I look back across South Bermondsey and Peckham past the ridge of hills where I grew up, to where the television transmitter stands on the ruins of the Crystal Palace. I spot the square tower of St Anne's Church rising above the riverfront buildings of Limehouse. And due west, past Strata SE1 at the Elephant and Castle, I make out St George's Wharf Tower, Vauxhall in the hazy distance. Oddly, the only major feature we cannot see is the Thames herself, obscured by all the buildings hustling in on her banks. Great slug of river. Strong brown god.

Map on top of Stave Hill. Photo credit, above. Photo credit, below.

The shouts of Sunday League footballers carry on the wind from the sports ground. Birdsong from the Stave Hill Ecological Park, a necklace of urban woodland encircling the base of the mound. A plane soars into the heavens from City Airport.

We are joined on the summit by a thirty-something man wearing jogging bottoms and a grey Hooters tank top. (The back carries the company slogan: 'Delightfully tacky, yet unrefined'.) He has a shaven head, carries a small towel, and sports the frame of a man who spends more time in the gym than is healthy. Two minutes later — as we are busy studying a scale model of the Surrey Docks that is, appropriately, half-filled with rainwater — another man joins him. He is panting and wearing more Lycra than is healthy. With his arty spectacles and designer stubble, he could be a media analyst or a trader. They set about using the railings at the top of the Hill to perform squats. Before too long they are sprinting up and down the steps, each time the second man letting out a more pained gasp than the last as he reaches the top.

In recent years Stave Hill has become a magnet for fitness enthusiasts; a kind of outdoor gymnasium for personal trainers and companies like Breathe Fitness, Wild Forest Gym and Bootcamp SE16. The latter maintains a lively Twitter feed, recording the exploits of its participants in tendon-crunching detail — from 'strength circuits' and 'endurance drills to improve cardio levels' to 'single leg tyre squats for ultimate glute and core strength' and 'crab crawls up Stave Hill'.

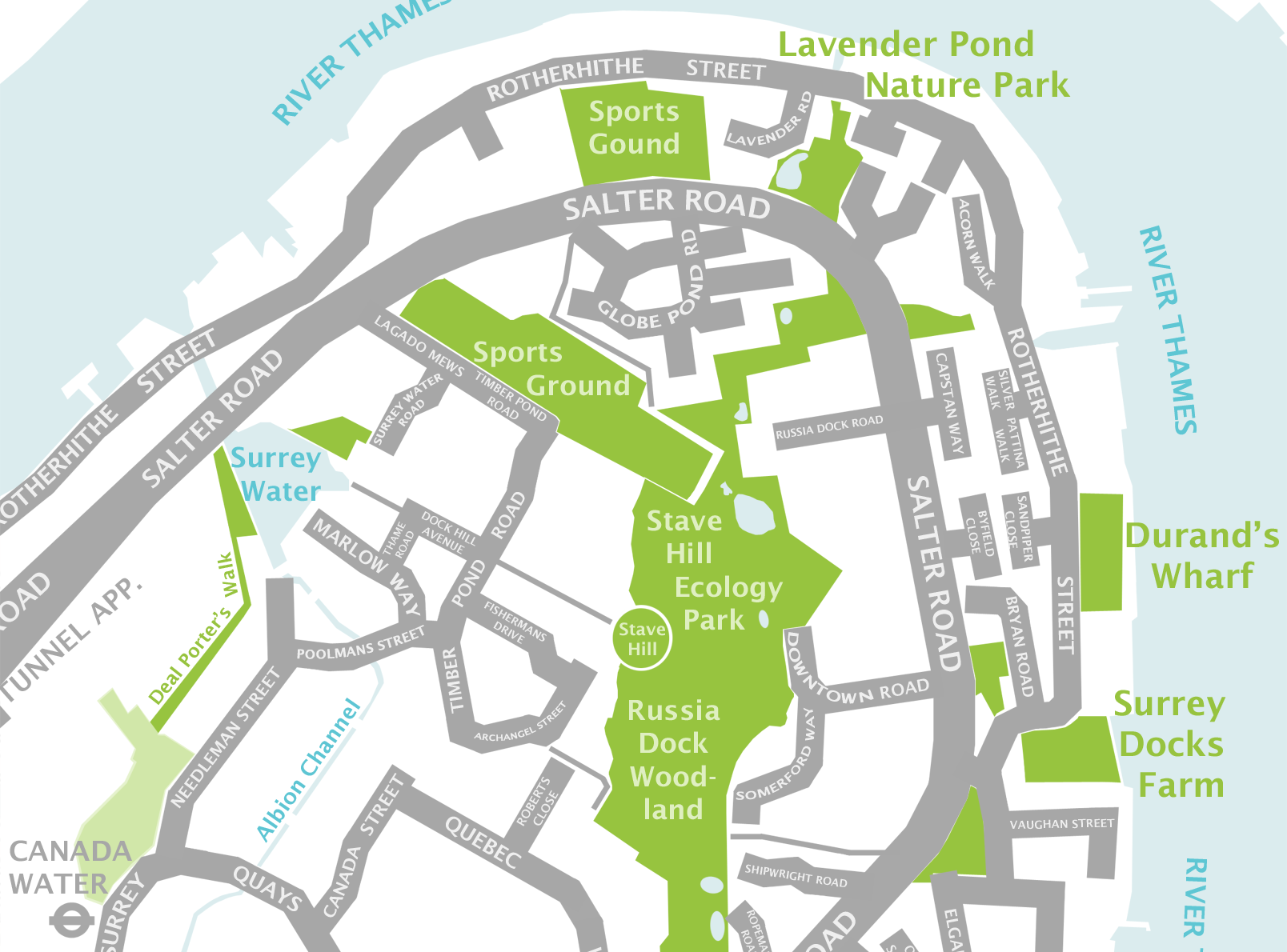

Map of Stave Hill Ecological Park (SHEP).

Beneath the skin of this place lies a forgotten history of labour — of stevedores and deal porters testing their strength and skill against steel and timber. But in Stave Hill the ruins of their yards are refashioned as a recreational treadmill; the same territories reworked by the twenty-first century leisure-seeker in engineered sportswear and tracking his progress via a fitness app on his smartphone. The body, he proposes, may have topography too. Sculpt me a landscape of undulating pecs and quads. Level the surplus; pump up the rest.

It is a manufactured wildness that has reclaimed the old docks . . .

We descend the mound and head north, following a footpath deep into the Ecological Park, tracing the sunken line of an old dock channel, now brimming with dense foliage and infrequent bursts of colour where the Council has planted something exotic. A girl in Ugg boots passes by with a scruffy dog. Two Eastern Europeans smoking roll-ups. A young man with his arm in a sling and a pit bull the colour of sand. It is a manufactured wildness that has reclaimed the old docks, but it will do. Who knows the day when the tide will break in, to take back the flatlands? You will find us high up, close to the sky.

A view of Canary Wharf from Stave Hill.

This article was first published in The Journal of Wild Culture, August 15, 2014.

Add new comment