In the spirit of indefatigable activists . . . Ahed Tamimi and Israeli soldiers during a protest in the West Bank, 2012. [o]

I came here just to be bombed! Bush already has a bomb with my name written on it.

— John Ross (a claim to his NGO host while being ousted as a Human Shield, Daura oil refinery, Iraq, 2003)

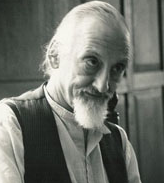

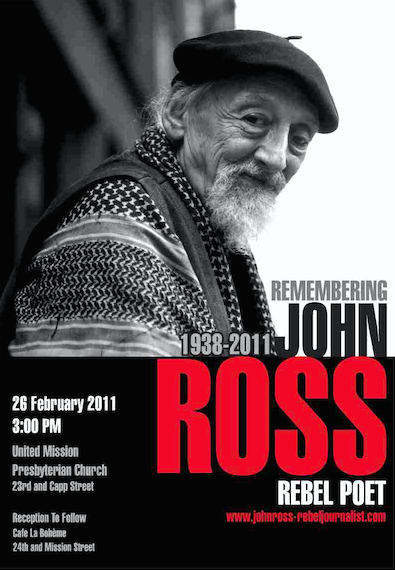

John Ross was bigger in spirit than a human body could contain. He was a “Red Diaper Baby,” a Beat poet whose stronghold had been the cafés and cantinas of The Village, an uncountable-cups-a-day espresso freak, and a non-stop news-breaking, award-winning periodista informing the world about Mexican politics.

Tom Hayden once told me that John was his favorite journalist — most likely for his razor-sharp reportage combined with witty double-entendres and down-home phrases like “a rat's ass.” The man had almost no teeth left after being beaten up for some political stand he had taken — and when I say “stand” I mean literally placing his bipedal body in the way of injustice. He was half-blind, having lost one eye after being hammered for another political stand; he had a bad back and walked with a limp for having been clobbered for another couple of political stands. He was loud and sure of himself. He was a man of irony, outrage, and courage.

He identified himself as a “rebel reporter,” an “investigative poet,” a “left-wing Mr. Rogers,” a “professional blurb writer,” and, toward the end, a “corpse-in-training.”

I say 'was' because John was beaten up once and for all by liver cancer in 2011. All medical intervention that could be done had been done, and he asked to leave his rooms at the Isabel Hotel in Mexico City's Federal District and be shepherded to the Michoacán village where he had raised a family and lived on-and-off for 50 years. It wasn't that we hadn't had sufficient notice of the possibility of his death, yet when I received the news, I sat in my chair for some time, as stunned as a baby bird slammed into a glass window. I was overcome with the feeling that I could not imagine — nor accept — a world without John Ross.

John was born on 11 March 1938 and raised in an apartment in New York City. His parents were Hollywood show-biz Commies, and before the age of 16 he had sold a joint to Dizzie Gillespie, babysat for Billie Holiday's dog, and gotten loaded at his mother's dinner parties with veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. From the moment of consciousness, just about every move he made was defined by politics and poetry.

"There he wrote his first tome, a pamphlet answering a crucial question — What to Do in Jail? "[o]

He first went to Mexico in 1961, where he and his lover Norma Melbourne landed in a village in Michoacán and built a casita. He also hung out in the Mission District in San Francisco, which was the heart of the Latin community. He had torn up his draft card during the US invasion of Lebanon in the 1950s, and he resisted the draft during the Vietnam years, for which he spent seven months at Terminal Island Penitentiary. There he wrote his first tome, a pamphlet answering a crucial question for those incarcerated. It was called What to Do in Jail.

The truth is that John didn't really find his vocation until 1984 when he was 56 years old. He became a Spanglish-speaking news correspondent with a focus on Mexico, and Pacific News Service sent him south to report. The job was a perfect fit. He trailed the Shining Path through Peru's jungles. He reported on resistance to Pinochet's dictatorship. He shadowed Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas' run for president of Mexico. He also met up with composer/author Paul Bowles in Morocco and the Basque separatist Euskadi Ta Askatasuna in Franco's Spain. When the 1985 earthquake devastated Mexico City, PNS sent him to report on los damnificados. He checked into the Isabel Hotel — and did not check out until 2010 when he left for Michoacán to die.

His second book won the American Book Award in 1995, Rebellion from the Roots, a chronicle of the Zapatista uprising in Chiapas on 1 January 1994, the first day of the North American Free Trade Agreement. He became a regular at Zapatista events, braving the long and muddy trek to their jungle hide-away, and at all events involving Mexican politics. The War against Oblivion, The Annexation of Mexico, ¡Zapatistas! and a novel based on voting corruption during Cárdenas' presidential bid, Tonatiuh's People, followed. He also penned ten poetry chapbooks.

When I saw that John was coming to Brodsky's Bookstore in Taos, New Mexico, to give a reading of Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos' children's book, La historia de los colores, I jumped into my old Jeep and made tracks northward. The book had been commissioned in 1999 by the National Endowment for the Arts to be published by Lee and Bobby Byrd's Cinco Puntos Press of El Paso, Texas. But when some of the anxious politicos of the Clinton administration got wind of the fact that US taxpayer monies were bringing a “subversive” document into print, they nixed the project. After some tense weeks, the Lannan Foundation of Santa Fe came to the rescue, offering up the now-revoked $7500; the book came out in glorious colors, and John was trotting about the US promoting it.

Broken plastic shrines of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, photos of loved ones, wayward underpants found in the Arizona desert. The source of his devotion to the border was obvious . . .

Somehow, in the commotion after the reading, I ended up in the same caravan with John and his lady-love of the moment, headed for a late-night dinner at some dowager's adobe, and it was here that our friendship began. It was nurtured across the distance — Chimayó, New Mexico to Mexico City — by none other than . . . the internet. Yes, John Ross was the guilty party who got this Luddite clacking away on a computer keyboard — and, for his wild notions, sleight-of-hand use of language, and utter dedication to friendship, it was worth every byte.

Our first poetry reading together took place at my house in Chimayó and went on into the night, lubricated by a bottle of red wine — I audience to his poems, he to mine. Our second was in El Paso. We were scheduled, along with publisher Bobby Byrd, to read at La Fe Cultural Center. The afternoon of the event John was all excited about an archeo-art exhibit made of Mexican indocumentados' used water bottles, dirty, ripped cachuchas, broken plastic shrines of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, photos of loved ones, and wayward underpants found in the Arizona desert. The source of John's devotion to the border was obvious; mine sprung from my labors as something of an underground railroad for incoming, deported, and departing immigrants in northern New Mexico. We set out to find the show. Of course, neither of us knew north from south in El Paso. We ended up driving around and around, only to find the building housing the exhibit locked shut — and an even worse tragedy: no espresso machine in sight. We stopped to down some chile-smothered hot dogs, which appeared to be the only semi-life-like foodstuff available, and after a grueling search for something/anything to eat, it seemed up to me to make up the Official Cuisine of El Paso. Sitting in plastic chairs on the sidewalk, John regaled me with gritty tales of the down-and-out denizens of his 'hood in Mexico City and the 1997 massacre of peasants in Acteal — the government's cruel retribution for the existence of the Zapatistas.

"Monstrously entertaining and tenderhearted view of “chilango” history on the eve of the centennial of the Mexican Revolution." — Kirkus Reviews >.

With the arrival of the millennium, John went on to resist the incursion of Israeli settlers into Palestinian olive groves (where they bludgeoned him with clubs) and act as a Human Shield in Iraq to prevent the US from attacking; upon their arrival Donald Rumsfeld threatened that if any of the Shields survived they would be prosecuted for war crimes for impeding US bombs. In the early 2000s John also wrote a creative memoir entitled Murdered by Capitalism in which, while imbibing Gallo wine and smoking PCP-laced pot in a Humboldt County cemetery, he meets the ghost of anarchist Edward B. Schnaubelt (1901-1979) and together they compare notes on the burial of the Old Left of Schnaubelt's era and the New Left of John's.

Upon returning to the Israel, he wrote what was to be his last book, El Monstruo, a monstrous tribute to Mexico City.

Through the years John identified himself as a “rebel reporter,” an “investigative poet,” a “left-wing Mr. Rogers,” a “professional blurb writer,” and, toward the end, a “corpse-in-training.” During his last round of chemotherapy, he attended the traditional Day of the Dead celebration in San Francisco's Mission District dressed as a cancer-ridden liver. His last wishes echoed those of socialist Joe Hill — that his ashes be scattered in a diversity of locations. In John's case, in the ash trays at the Hotel Isabel and along the #14 bus route through the Mission, mixed with marijuana and rolled in a joint to be smoked at his funeral.

In early 2010 John, half-blind and barely able to walk, braved the rail-runner from Albuquerque to Santa Fe to visit me while on a book tour. The mission was to swig espresso, buy a really cool, Pueblo-crafted cane to bolster his failing leg, and (needless to say) talk politics. I was on the verge of moving to Bolivia, and at a little café by the tracks he reached into the suitcases of memory to regale me with his encounters with Evo Morales before the man became El Presidente of that country — the major theme being the clash between John's aspiration to discuss anti-imperialist strategies and Morales' obsession with ogling passing women.

Although neither John nor I said a word, when he mounted the aluminum steps for the return journey, we knew it would be the last time we would be together. Hyper-focusing every cell of my body, from eyeballs to toe nails, I clung to the vision of this valiant warrior as he hobbled to grab the overhead bar and plop his wiry body into a seat. ō

In the Company of Rebels

New Village Press. Publication date, April 30 2019

288 pages, 6 x 9 inches, 129 black & white photographs

CHELLIS GLENDINNING is an essayist, poet, psychotherapist, yoga practitioner, and the author of nine books — the latest being Objetos (La Paz, Bolivia: Editorial 3600, 2018). She lives in Chuquisaca, Bolivia.

Comments

With Ross being my last name

With Ross being my last name and Mexico being my favourite country after Canada, I couldn't resist reading this tribute to John Ross. I'd never heard of him despite our sharing a love of Mexico, a last name and a home in Michoacan.

As I embark on writing a profile of my own, I'll look back on Chellis Glendinning's moving piece. It brought a lump to my throat as I read about the corpse-in-training mounting those "aluminum steps for the return journey."

Lovely,

Nicola Ross

I really enjoyed this feature

I really enjoyed this feature on John Ross. I wish I could be a beatnik rebel poet when I grow up.

Great tribute. I just want…

Great tribute. I just want to add one of John's haunts was Humboldt County, California, Arcata to be specific. Plenty of poetry happened there, as well as poker games with friends Tim McKay and Sid Dominitz. I interviewed John on the radio LIVE from Iraq a couple days before the war, when he and Code Pink and others went to act as human shields. John Ross made poetry and journalism — and he made history.

Thank you for your lovely…

Thank you for your lovely words about my father, John.

Add new comment