This year beekeepers in Canada have had losses of up to 90 per cent amid spread of Varroa destructor and other factors. [o]

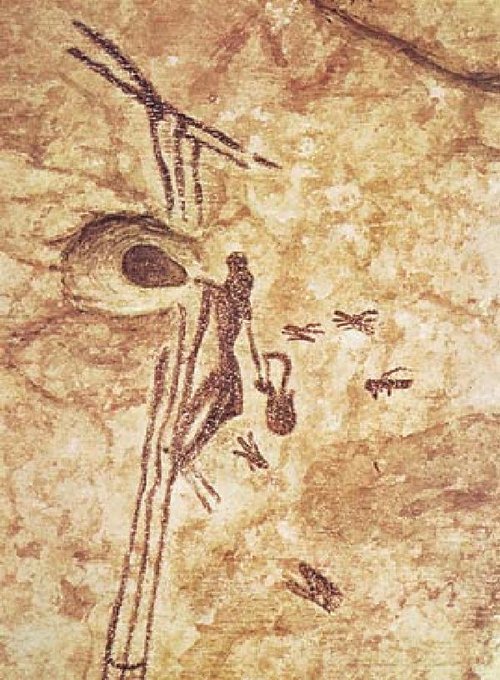

Prehistoric rock paintings in Spain, showing a human figure collecting honey, reveal that hunter-gathering from beehives is an ancient practice dating back 7,000-15,000 years. Spain remains renowned for its honey to this day, and bees on the island of la Palma proved to be particularly resourceful, when thousands of them survived for weeks covered in volcanic ash following the eruption of the Cumbre Vieja Volcano last autumn.

Rescuers had to wait 50 days before it was safe to visit the hives and were amazed to find that bees in five of the six hives, located 600 metres away from the volcano, had survived. Despite the intense heat and toxic fumes from the eruption, the bees stayed alive by sealing themselves in the hive and feeding on existing stores of honey.

It is likely that these bees have been living on the 400-acre Oxfordshire estate for hundreds of years.

Honeybees are the only insects that store food in excess. Apis mellifera, the European honeybee, is the most commonly-kept species and the only one kept in America. They were introduced there in the late 1600s and are now integral to the current agricultural system. As our most important pollinators, bees are vital to the production of around 40 per cent of crops, including avocados, onions, almonds, apples and other fruit. The remaining 60 per cent are the staple crops of wheat, rice and corn which can either self-pollinate or use wind-assisted pollination. If bees disappeared from the face of the earth, humans would not die out soon afterwards, as is sometimes claimed. But such an event would have a catastrophic effect on ecosystems, leading to food shortages and soaring costs of produce.

Amid so many reports of insects dying off due to pesticides, disease and loss of habitat, there is encouraging news about rare wild honeybees, once thought to be on the brink of extinction. The only known surviving descendants of Britain’s native tree-nesting honeybee population have been found in self-sustaining colonies in the ancient woodlands at Blenheim Palace in England. One of the nests is estimated to be at least 200 years old, and it is likely that these bees have been living on the 400-acre Oxfordshire estate for hundreds of years. The woodlands are not open to visitors and no cultivation takes place there, resulting in a relatively safe and closed environment for the bees to thrive unhindered. The nests are built in tree cavities 15 to 20 metres off the ground, with entrances measuring only 5cm diameter or less. Despite several ecological surveys over the years, they have remained undetected until now.

A figure gathers honey from a hive on a cliff face in this 8,000 year old painting discovered in Arana Cave in Spain. [o]

Wild bees are very hardy and have been recorded foraging among the treetops at temperatures as low as 4C, allowing them to carry on collecting nectar late in the season (most bees stop flying at 12C.) Wild bee hives have more than one queen, sometimes several, which helps to ensure the survival of the colony. The Oxfordshire colonies showed no signs of being affected by Varroa mite, a lethal parasite which has had a devastating effect on bee populations, suggesting that the wild bees may have evolved to possess a natural resistance to these mites.

In response to the global problem of bee losses in the last decade, the research association COLOSS (from COlony LOSSes) was set up in Bern, Switzerland. According to one of its publications, Global Efforts to Improve Honey Bee Colony Survival, the Varroa destructor mite is the most significant threat to the survival of Apis mellifera, though some hives throughout Europe remained unaffected. This year beekeepers in Canada have had losses of up to 90 per cent amid spread of Varroa destructor and other factors.

Five hives that held tens of thousands of bees were covered for weeks in ashes expelled by the Cumbre Vieja volcano. Beekeepers and scientists were delighted to find that they had survived. Photo: Elías González, La Palma Bee Keepers Association. [o]

Honey Bee Watch, a citizen science initiative of COLOSS, recruited volunteers to help with research and identified 44 stable colonies of bees which had survived without any treatment to control mites. The findings suggest that the ability of honeybees to survive Varroa infestation may be more common than first thought. A further study, 'How Honey Bee Colonies Survive in the Wild: Testing the Importance of Small Nests and Frequent Swarming,' found that colonies in small hives swarmed more often, had lower Varroa infestation rates, less disease, and higher survival compared to colonies in large hives.

Bee-keeping dates back thousands of years, but recent research suggests that the well-established method of using standardized wooden boxes as hives, while convenient for humans, may deprive the bees of the natural conditions in which they thrive and could leave them more vulnerable to parasites and disease.

Low-temperature scanning electron micrograph of V. destructor on a honey bee host. [o]

In Germany’s national park in the Black Forest (Schwarzwald), colonies of wild bees have been found nesting above ground. The park’s researchers, who are partnering with the University of Freiburg, found that the presence of deadwood increased their activity. Bees sometimes nest in dead trees, so a restoration project was undertaken to create areas of deadwood in the coniferous forest. “These plots provide a more diverse, varied habitat," reports Tristan Eckerter, chair of Nature Conservation and Landscape Ecology at the University of Freiburg, "and as a result we would not have thought to have found so many different wild bees."

The book, Wild Honey Bees: An Intimate Portrait, by Jurgen Tautz and illustrated by wildlife photographer Ingo Arndt, proposes that many of the problems affecting bees in commercially managed hives today can be understood by the change of a more wild habitat to cultivated land, making them effectively domesticated, compared to their ancestors, the wild honeybee, that live in tree cavities among other insects in a mini-biome and are what Tautz calls “creatures of the forest.” This is borne out by the activities of the bees at Blenheim. Conservationist Filipe Salbany believes that they could even be a distinct eco-type, a species specifically adapted to that location.

Blenheim bees are handled without protective kit as they are ‘extremely relaxed’. Photograph by Filipe Salbany. [o]

“These bees are unique," explains Salbany, "in that they live in nests in very small cavities, as bees have for millions of years, and they have the ability to live with disease.” He suspects that there are other colonies of wild, tree-nesting bees yet to be discovered, adding: “We need to protect our ancient woodlands. Because that’s where we are likely to find these bees.”

From the peak of a volcano to the depths of the forest comes a message of hope, borne on the wings of a bee. ō

ANGELA LORD is a freelance writer with a degree in Modern Languages and a background in print journalism. Originally from South Yorkshire in the UK, she is now based in Surrey.

Comments

How fascinating, Angela…

How fascinating, Angela. Thank you for a most informative read.

What a wonderful article,…

What a wonderful article, thank you! I've shared it along with friends.

Add new comment