Pokrovsky Church, Vladivostock. [o]

I first set foot in a church as an impressionable young teenager. It was the only church in Vladivostok, the city where I grew up. I entered alone, out of curiosity, drawn to the promise of comfort and solace that I did not find in my fractured family life, my parents constantly on the verge of divorce.

The road to the church passed by the local police station, put there for a reason perhaps. For decades after the Russian Revolution in 1917, the Soviet state police routinely surveilled and persecuted churchgoers. In those years, going to church could easily cost one a job, university admission, or freedom. But by 1989, the restrictions had slightly eased.

Slightly out of breath as I walked uphill, I passed small houses, many of them built of wood and worn out by decades of rain. I took care to avoid making eye contact with passersby. Entering through the large, black, wrought-iron gates into the courtyard, I found myself in front of whitewashed church walls with tall, narrow windows — the entire edifice crowned by raindrop-shaped golden domes topped with glittering crosses. When I approached the heavy wooden door with decorative carvings and tugged on the hefty handle, it didn’t move. I hesitated, walked down the steps and around the church and came back to the entrance. Suddenly the door swung wide and a woman wearing a head scarf stepped out. I hastened in. The door and the church were in fact open — I only would have needed to pull harder.

“Despair is a sin,” she replied. “Plus . . . you need to get baptized.”

Inside, a small choir sang in Church Slavonic, an ancestor of modern Eastern European languages that I, like most Russian speakers of the modern era, did not understand. I saw traditional iconic images of saints painted as frescos on the walls and tall sanctuary doors; also gilded and decorated with full-height icons. The 30 or 40 worshippers were standing or walking slowly from icon to icon, lighting candles in front of them, kissing the glass covers or the gilded frames. All-male clergy wearing floor-length embroidered robes led the service, sometimes chanting or reading in front of the people and often stepping away from the laity to officiate behind the closed sanctuary doors. Every woman in the church was wearing a skirt or a long dress and had her hair covered with a kerchief.

When the afternoon service had finished and brusque ladies in head scarves walked from icon to icon extinguishing the candles, I settled into a small chair in a corner and started to cry.

One of the church ladies approached me. “What’s happening?”

I babbled something incoherent about family troubles, and how I was feeling lost.

“Despair is a sin,” she replied. “Plus, you need to get baptized.”

I felt slightly disappointed that she did not suggest an immediate and more practical way to soothe my sadness.

My generation of Soviet children born in the 1970s caught the tail end of the state-enforced atheism. I don’t remember my parents, who were university-trained scientists, ever talking to me about faith. If my father had mentioned anything related to religion, he probably would have repeated the Leninist slogans proclaimed since the Russian revolution: “There is no God. Religion is the opium of the people.” In my primary school, the images of Marx, Engels and Lenin were painted on a hallway wall. Starting from the second grade, all schoolchildren had to wear a small pin on their uniform with the face of Lenin. From grade 4, the pins would be replaced with a red neck tie, indicating mandatory membership in the “Young Pioneers”, a Communist youth organization modelled after the Boy Scouts.

"The [Young] Pioneer is a friend of children from all countries of the world." [o]

Childhood in the Soviet Union shaped my understanding of science. I grew up a lab rat, or perhaps I should say a lab-trained sea urchin. When I was three months old, my mother, a biologist and passionate diver, embarked on a small passenger boat with my older sister Dina and me. After several hours of travel in rough sea conditions from the Russian Pacific port of Vladivostok, we arrived at Vityaz Bay, a small marine cove near the border with North Korea, to join my father on a recently founded marine research station. There he was building an aquarium facility that would be as advanced as the Soviet research budget allowed — which is to say, shoe-string.

A crystal-blue body of water surrounded by rolling hills, Vityaz Bay still visits me in my dreams. Every spring, the hills lit up with the pink and violet of wild azaleas. In summers, cool summer fogs enveloped the pines on the craggy rock outcroppings. Adding to the mystery of the Vityaz Bay, two abandoned wooden whaling ships half-submerged in the water haunted the imagination of all kids who lived at the research station.

Next to the shore stood a two-story, white brick building where my parents kept marine animals in plexiglas tanks and ordinary bathtubs filled with seawater. In the aquariums were starfishes, sea urchins, mussels and clams, and even a two-foot-long octopus. The octopus did not like living in captivity, despite the algae-covered stones set up in his aquarium to imitate underwater caves. He tried to escape, climbing out of his open-top aquarium and crawling along the cement floors that were always wet with seawater. I rooted for the octopus, but he never did make it to freedom.

My parents’ house was filled with books on zoology, genetics, and biochemistry; oceanography manuals; sea maps; technical brochures; and volumes about underwater research and the beauties of the sea. Scuba tanks, fins, snorkels, diving suits and even an underwater harpoon gun cluttered the small home. For her doctoral investigations, my mother studied the early development of marine organisms, especially mussels and sea urchins. I loved coming into my mother’s lab, full of thick-glassed, round tanks with automatic stirrers replicating ocean waves and currents that would keep fragile, translucent sea urchin larvae afloat.

My father, the head of the marine research facility, helped visiting scientific groups carry out laboratory studies. He was also the one who put on the oiled coveralls and spent long shifts keeping the pumps running in the rigged-together pumping station that, with low-budget equipment, managed to supply fresh marine water to the animals in the tanks. His first and foremost scientific love was the then nascent field of immunology. In his lab, my father conducted experiments to understand how the simple immune system of sea urchins sufficed to protect them from internal and external diseases.

At home we did not talk about Darwin and evolutionary theory; materialism and evolution were simply viewed as facts. As he and I stood near the coal-fired stove in a kitchen without running water in our house overlooking Vityaz Bay, my father first showed me a thick book describing DNA as the “code of life”. And in the mid-80s, around the time the HIV virus was discovered, I sat on a creaky, worn-out sofa reading about AIDS in a hardback science book he’d given me.

Sea urchins are usually between 4-5"/10-12 cm in diameter; their venom is dangerous but not poisonous. [o]

When I was growing up, our family did not celebrate Christmas. Easter was different, and we looked forward to colored eggs and pascha, the sweet Easter cake with raisins. The night before Easter my mother would boil white eggs in water with lots of yellow onion peels (to impart a golden-brown color to the eggshells), the only available way to color Easter eggs. In the morning my sister and I would come to see our mother and say, as she taught us, “Christ has risen.” She replied, “Truly he has risen.” I had no idea what I was saying, who “Christ” was, or what “risen” meant. But I was excited to participate in this little game.

What led my mother — whose childhood passed in the last decade of Stalin’s rule where religion was suppressed most severely — to paint the eggs and say these words? Was she thirsting for a sense of spiritual fulfillment and protection? Perhaps living in a society that emphasized adherence to the rules — and, sharing her life with a man whose ideal of a wife was a homemaker, not a Ph.D. scientist — maybe the Easter eggs, pascha cake, and a small ritual with her daughters gave her a sense of peace she could not find elsewhere.

My own hesitant attempts to explore religion, nurtured by those secretive Easter rituals and the simple joys of toying with the painted eggs, evolved into a longing to touch the clandestine, prohibited spiritual world. There was a quiet inner sense that science and research alone did not have all the answers to my questions about growing up, about family and relationships. My curiosity toward different world views would take me to the United States, and eventually as far as divinity school in Boston, where I would search out connections between the sphere of science, in which I was brought up, and the realm of religion, which had beckoned me from whispered conversations and concealed manuscripts passed from hand to hand.

In 1994, my first year in the United States, in a log cabin in the rural community of Eaton, New York, Bonnie Duval laid some books on her dining table. “These Christian books explain why evolution is wrong,” Bonnie told me. Her smile stretched between full cheeks, softening a face framed by gentle blond curls. Having once earned her living as a seamstress, she usually wore an embroidered kitchen apron that she had sewn herself.

I leafed through the books, surprised to see that they were not about Christ, grace and salvation — like other books and stories this family had shared with me. Instead, they featured pictures of dinosaurs and fossil bones and rebuked Darwin, Darwinism, and the evolutionary theory that I had learned in high school and college. They also talked about the Creation of the Earth, and argued that the Earth was quite young, much younger than the estimates of solar system age advanced by astronomers and physicists.

As an 18-year-old exchange student from the just-collapsed Soviet Union, studying biology at Colgate University, I had never met anyone like Jim and Bonnie Duval: a Bible-reading, churchgoing, evangelical couple who had adopted four children from a troubled family and, even though they were not well off, welcomed neighbors and hapless foreign students to their home for meals. Bonnie was the rock of the family, keeping her faith and encouraging everyone even when the family depended on food donations during the months that Jim lost his job.

Vityaz Bay, a small marine cove near the border with North Korea. [Photo courtesy of the author.]

Occasionally they took me to services in local congregations where the pastor would ask all those who considered themselves “saved and headed to Paradise” to rise. Jim and Bonnie would stand up, but I always vacillated: remaining in my seat seemed impolite. I feared disappointing my new friends. But Paradise? I had no idea what the pastor was talking about.

Jim and Bonnie didn’t seem to mind that I did not rise with the rest of the congregation. After the services they cheerfully introduced me to their church acquaintances as the visiting student from Russia. I smiled shyly and shook hands, looking forward to the little ham and cheese sandwiches offered in the fellowship hall.

The transition between the world of my childhood and life at Colgate was enormous. Before Jim and Bonnie took me under their wing, I knew no one in the local community. And I felt lonely and poor in a school for well-off teens who partied on weekends. All my mother had to give me before I boarded the flight to the US was a hundred dollars — plus a little plastic turtle (the kind that toddlers play with in the bath) she’d wrapped up and placed in my luggage: to open on the first birthday I’d spend away from home. When I opened the gift wrap, six months after I arrived in upstate New York, I discovered one of the turtle’s legs had broken off so it could no longer float. I cried.

Still, despite my initial bewilderment, all the discussions with the Duvals about the Creation of the Earth, so different from the evolutionary theory taught by my high school and college teachers, did not cause an internal conflict. This American family — with guitar, lawnmower, and hot dog dinners with mashed potatoes — welcomed me with warmth and care, giving me a sense of home and friendship. That mattered to me a lot more than the age of the Earth.

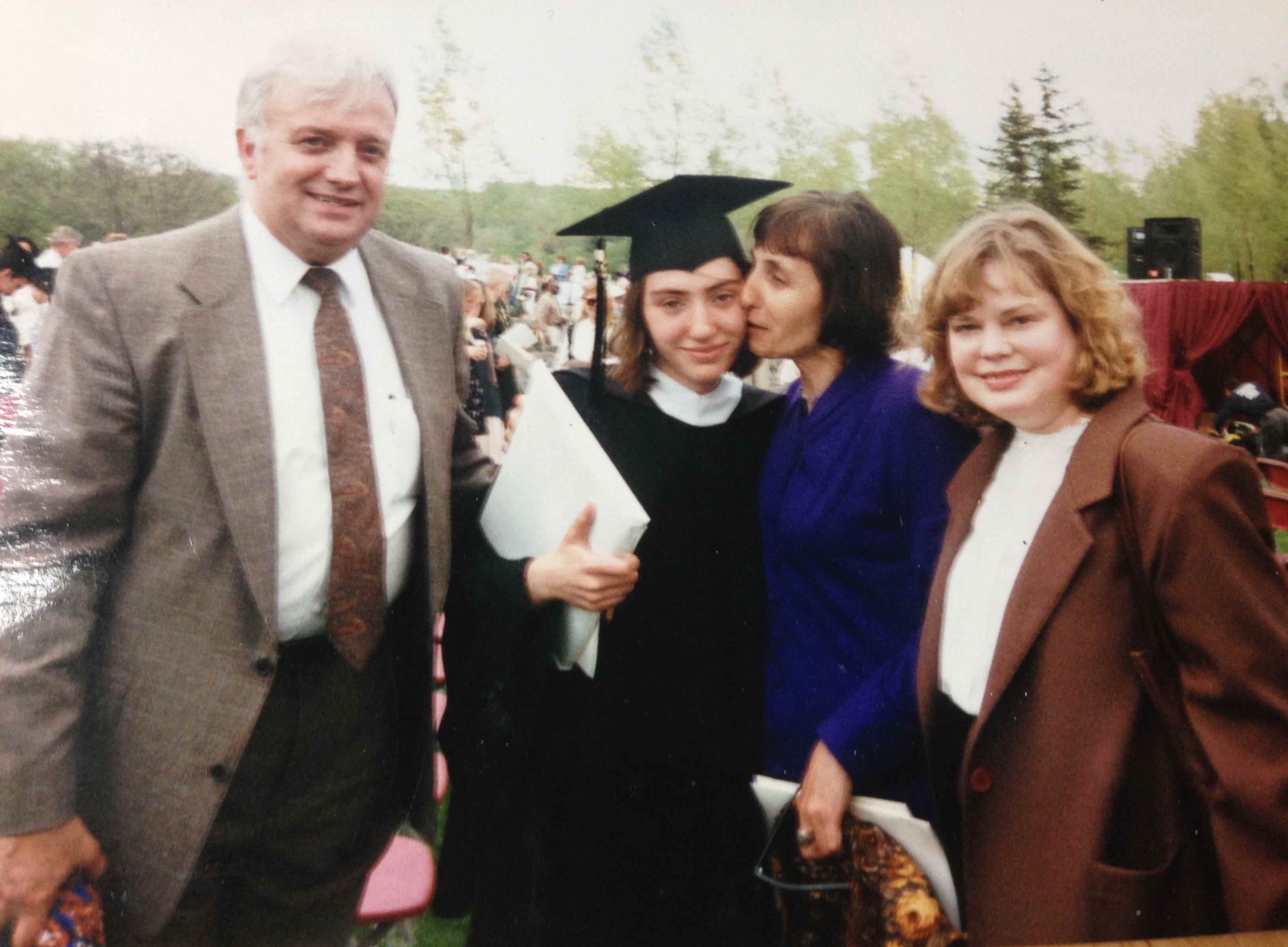

In my Colgate graduation photo there are four people. On the left, Jim, towering above the of us, and wearing a light-brown suit and tie, his hair already white. On the right, Bonnie, sturdy and strong, much shorter than Jim, with her blond curls and sincere, direct gaze. My mother and I are in the middle of this beaming group posing for a photograph. My mother is kissing my cheek and I am wearing a funky medieval cap and gown and holding a diploma, on which the word “Valedictorian” stands out in a paragraph of Latin. My mother had travelled to the United States to celebrate my graduation, and to see me off to graduate school in California. I would see Bonnie and Jim only once more, in 1999, when they came to visit me in San Diego where I was doing doctoral research at the La Jolla Institute of Allergy and Immunology.

Just as our fingers can scan the surfaces of objects and detect shape, texture, and depth, white blood cells can touch other cells with their cell surface molecules, called receptors.

My first winter in Southern California, 1997–98, was the year of a very heavy El Niño. I hand-sewed wide, baggy pants and a cape from grey nylon and biked to the lab every morning in the pouring rain, arriving mostly wet (budget-grade nylon fabric was only partly water-resistant). I worked late and sometimes slept the nights curled up between two chairs in the second-floor research library, its large windows overlooking the La Jolla mesas and canyons covered with short brush and cacti.

At the La Jolla Institute, I researched the molecular basis of the immune response to bacteria and viruses. Just as our fingers can scan the surfaces of objects and detect shape, texture, and depth, white blood cells can touch other cells with their cell surface molecules, called receptors. Viewed in this way, the immune system, one could say, detects danger and distinguishes between friend and foe through tactile recognition. Using genetic methods, I sought to understand the function of a group of cell surface receptors whose DNA sequences are highly similar in all mammals studied: mice, dogs, humans, horses, pigs, chimpanzees, alpacas, bats, guinea pigs, rabbits, cows and pandas. From the evolutionary biology perspective, such genetic sequence similarity is described as “highly conserved.” My PhD thesis was built on the premise of historical evolutionary relatedness of these immune receptors, which I described as a family of proteins that play a similar role in the immune systems of very different animals.

All research literature in peer-reviewed scientific journals that I read affirmed this view of genetic relatedness of all species. In my peer groups — in the lab, my graduate university, and all other universities I have ever visited — evolutionary theory was our framework, inspiring and productive, while religion (if ever mentioned) was relegated to the sphere of personal preference — and entirely unrelated to science.

To the surprise of many, in 2005 I left a university research position to study at Boston University School of Theology, a seminary of the United Methodist Church, because I sought to explore the world of religious faith from a spot as close to the source of authority as possible – at a divinity school, training side by side with future faith leaders. The men and women who studied at this seminary to become pastors wanted to learn about science in addition to religion and were willing to question the nature of the faith itself, looking for deep answers that could satisfy themselves and their future congregations. These two years of studies helped me see clergy not as unapproachable authority figures or holders of some kind of unique truth but as people who were trying to do their best, even when they themselves might not be fully certain what the “best” was.

What stayed with me after I returned to scientific work from my sojourn at the School of Theology was a sense that religious faith is more than a mere set of beliefs; rather, it is something that grows out of practice. It’s everything and anything we carry out in our everyday lives, what we do to other people and with other people. This is true of science as well. Science is not just a stack of library textbooks, but the pursuit and exploration along the journey.

The eroded cliffs of Torrey Pines State Natural Reserve, with La Jolla barely seen in the background. [o]

Until the 19th century, most scientists possessed some degree of schooling in religion and theology, whether or not they chose to enter into a bitter battle with religious authorities, as did astronomers Galileo and Giordano Bruno. Or whether they relied on the comfortable church facilities to conduct their experiments, such as Catholic abbot Gregor Mendel, whose research on inheritance in peas helped found the modern science of genetics. Today, I am a rare example of a PhD research scientist with formal training in theology. From this perch I have discovered that the most interesting and productive conversation in the spheres of science and religion — and the intersections between the two — focuses on caring for the world around us.

Perhaps the stunning, multiform world of biological diversity around us has indeed come from evolution, and through an unimaginable succession of geological epochs whereby fish begat frogs, frogs begat dinosaurs, and dinosaurs begat birds. And then the primordial birds begat many other birds that, like Darwinian finches, adapted to every possible ecological niche on planet Earth, and the primordial mammals begat everything from whales to mice. I had read that story of evolution in the science books my father gave me long before I had seen a dinosaur fossil first-hand, or learned to analyze genetic sequences with modern computer-based machinery. I still find it compelling and fascinating.

My return to La Jolla in 2007 marked the moment when I first saw “geological time” with my own eyes: I was standing on the shore underneath the Torrey Pines cliffs, studying the layer of ancient fossil shells embedded in the soft siltstone. I touched the crumbly shells, recognizing what looked to be mussels and oysters. I could imagine that once upon a time this soft rock was the bottom of the sea, and the embedded shells were living creatures. Hundreds of thousands of years had passed and the former bottom of the ocean had risen to become tall cliffs.

If you were to ask me today about evolution, I would tell you about the Torrey Pines cliffs that reminded me of Vityaz Bay and my love for the ocean, and those crumbly, fragile white fossil shells I stroked with my fingers. And I would share with you my story of learning about faith and scientific research through my life, linking Russia and the United States.

Graduation from Colgate, May 1995. Jim Duval, the author, Olga's mother, Tamara, and Bonnie.

Bonnie and Jim Duval live alone in Kentucky now, their adopted children all grown up and spread out in different states across the country. Working on this story helped me reconnect with the Duvals as I thought back to my first year in the US and one family’s generosity during such a lonesome time in my life. After reading the story, Bonnie emailed me back within an hour: “My husband has had dementia these past seven years,” she wrote, “but it has not yet affected his long-term memory. Jim cherishes the times we spent with you and remembers when you helped him paint our small, hip-roof, red barn on a very hot summer day, and how you had once walked from Colgate to our home for several miles, barefoot on a parched country road.”

She added, “To this day, I am unsure how old the Earth actually is, but I do know that without Jesus and the love of God, I could not have survived in this world.”

At a distance of over a quarter-century — from the moment when I first set foot in church — debates over science, evolution and religion pale in comparison to human kindness and being faithful and loyal to those who helped me on my journey and extended a supportive hand. ≈©

OLGA NAIDENKO is a research biologist trained in theology who grew up in Vladivostok, Russia. She now lives in Washington, DC where she works in the field of environmental policy. This essay is Olga's first non-fiction work, developed under the Think Write Publish Science and Religion fellowship program.

Comments

Beautiful, heartfelt, deep

Beautiful, heartfelt, deep yet simple. Brought tears to my eyes.

Olga, this is such an honest

Olga, this is such an honest and heartfelt piece. I so wholeheartedly agree with your last sentence about human kindness, faith and loyalty. I struggle to explain my faith to anyone, other than to say that God is Love. The commandment from the Bible, "Love one another as I have loved you," is what stays with me, and I try to follow that — in my own flawed way. May you continue to find human kindness in your life and work. Thank you for sharing this piece.

Add new comment