Ghost Pipe, Monotropa uniflora. [o]

In recent years the ghost pipe plant has become a popular wild harvested herbal remedy for pain, grief, and anxiety — all despite ecological research gaps and the fact that the evidence base for such uses is insubstantial. Aside from this, ghost pipe is a charismatic and enchanting plant worth knowing about, not just for its unique biological character but also as a narrative reflection of mutualism and parasitism as it relates to the human condition.

Ghost pipe (Monotropa uniflora) is striking in that it is a mycoheterotroph1, a plant that grows from fungi. Lacking chlorophyll or photosynthetic processes, it obtains its carbon from mycorrhizal fungi in the soil. This allows it to flourish in dense, shaded temperate forests where sunlight is scarce. And, from a forager’s perspective, the ghost pipe’s distinctive and ethereal appearance draws us in. It is white with Victorian-pale translucent petals and scales − a gesture like a paintbrush lifting off the canvas. And, it evokes a sense of gentility and care: as if you want to care for it, but also want it to care for you. When it is harvested and extracted in alcohol, this white plant turns into a purple extract. For me, it makes me want to hold it up to the light and use it to invoke magic. Search results for ghost pipe will take you to blog posts portraying it as a remedy for pain, grief, and anxiety — you will even find claims for its use as an opioid substitute — and take you to advertisements or product listings on Facebook, Etsy, Amazon, and eBay. On these platforms you can find tinctures, infused honeys, roll-on topicals, many product listings claiming these “amazing effects.” Google searches for ghost pipe have increased in recent years alongside blog and social media posts about the plant. They rise in the early 2010’s with a noticeable uptick in 2016 (Google Trends 2022) and increase dramatically from 2020 to the present. They spike in midsummer (when it blooms) and are most concentrated in the northeast and northwest corners of the United States (where it is most abundant).

'Cheaters' are species that steal the benefits of the mutualism without providing anything in return.

What is the basis for the current popularity of ghost pipe? Contemporary herbal interest originated with a group of 19th-century physicians known as the Eclectics. King’s American Dispensatory is a key reference text for them and is referenced widely in the herbal blogosphere. Ghost pipe is described here as a remedy for convulsions, anxiety, and pain (Felter and Lloyd 1905, p. 1277). The origins of this entry are an 1881 case report detailing the use of 5 drops to treat convulsions in a pregnant woman ('Monotropa in convulsions,' 1881). No other clinical or treatment details are available, and the original author is unknown. Worth noting, there are no biomedical or ethnobotanical studies or published literature supporting the use of this plant for any health-related purpose

Despite its popularity, there is still much to be discovered about ghost pipe’s biology and ecology. Its dependence on delicate soil ecology renders it vulnerable to anything affecting forests, such as droughts, fires, nitrogen runoff, timber harvests, and logging activities. We know a few things about pollination and reproduction: it utilizes Bombus pollinators and reproduces through dust seed production (Klooster and Culley 2009; Bidartondo 2005, p. 346). While germination chronology and mycorrhizal influences have been explored with a related Monotropa species (Leake et al, 2004), cultivation methods have yet to be determined. It is therefore only found in the wild.

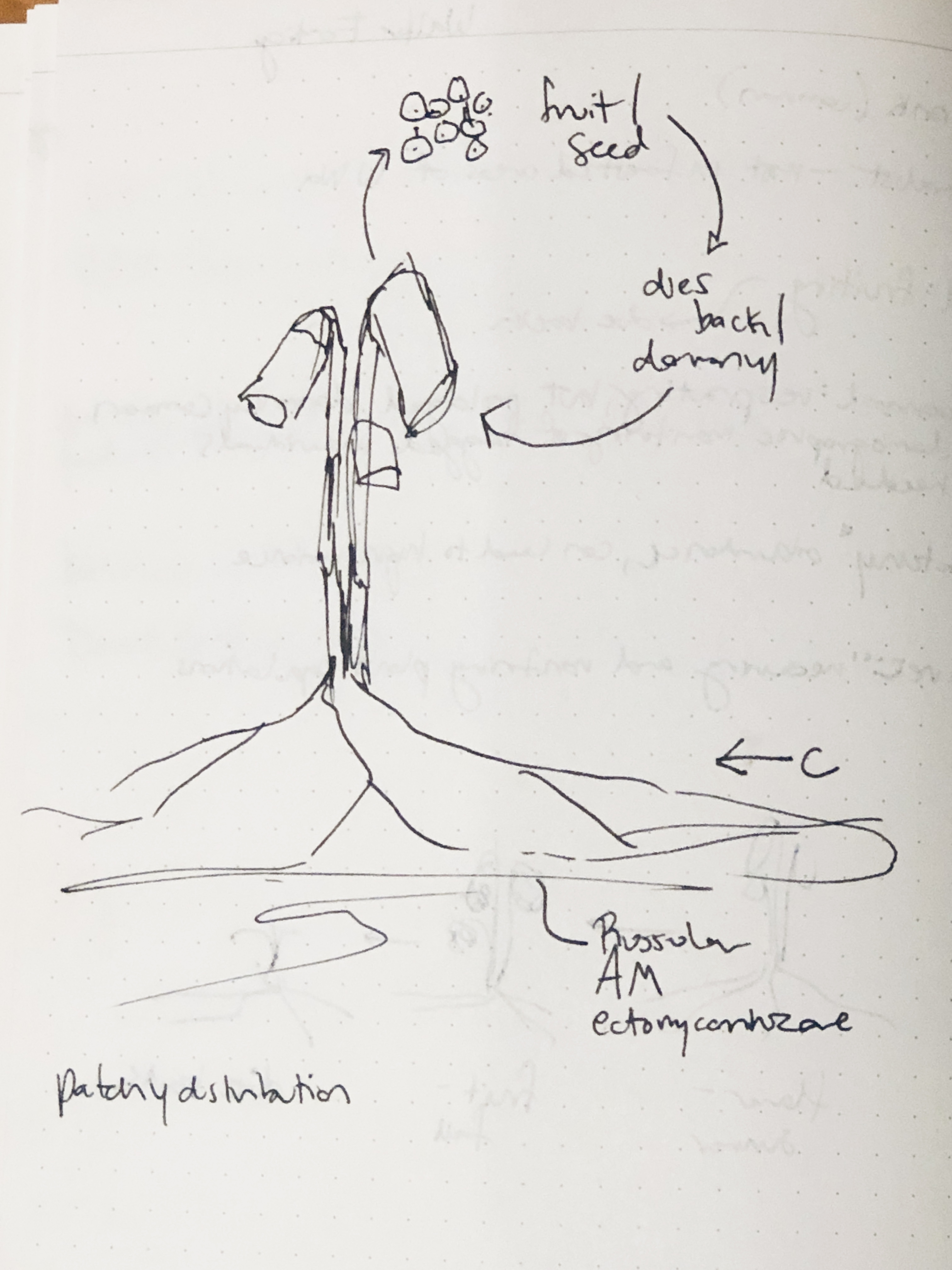

Author sketch.

Ghost pipe is also known to enter prolonged periods of dormancy lasting up to several years2. This makes it difficult to monitor stands over a long period of time. The reasons for these dormancy periods are unknown.

As a mycoheterotroph, the growth and development of ghost pipe is limited by the carbon it can sequester from Russula brevipes, a white mushroom widespread in North America, also known as ‘short-stemmed russula’ or ‘stubby brittlegill’ that grows in a mycorrhizal association with trees, especially fir, spruce, hemlock, and Douglas-fir (not a true fir). Carbon-limited plants like ghost pipe adapt anatomically to reduce carbon loss to respiration, such as producing scales instead of leaves. The impacts of harvesting the roots and aerial parts of the plant have not been characterized or reported in the scientific literature. Finally, any negative impacts to Russula brevipes, such as devastations to soil structure, contamination, or destruction to host trees, will also harm ghost pipe.

Despite these significant data deficiencies, ghost pipe’s global ecological status is ranked by NatureServe 2022 as G5/secure. However, local realities vary widely. In some states like California, the plant is rare and threatened. Many states in North American have no status rank or missing data altogether. As a result of NatureServe’s secure global ranking, few consider its ecological status or future.

Pink Indian pipe is another name for ghost pipe that is displaying a pink coloration. [o]

What does it mean to be in a mutualistic relationship with a plant or a forest? Mycoheterotrophy inspires contemplation in interdependence, parasitism, mutualism, the human condition, and relationships to other species. The evolutionary origins of mycoheterotrophy point to a defection from mutualism to trophic “cheating”. (In the field of mutualism, as reported in Science Daily3, “cheaters are species that steal the benefits of the mutualism without providing anything in return. An example of one of nature's cheaters are nectar robbers. Nectar-robbing bees chew through the side of flowers to feed on nectar without coming into contact with the flower parts that would result in pollination.”) This is considered the result of a mutation affecting chlorophyll production in the most recent common ancestor of ghost pipe and its closest green plant relative that participates in plant-fungal mutualism (Bidartondo 2005, p. 336). Ghost pipe is often described as a parasite: that is, what was once a mutual relationship becoming unidirectional. Though it is not known whether a parasite has ever returned to mutualism following defection from its original state, we could embody it — the seeds are there. They may be small, but so too are the seeds of ghost pipe. Yet for seeds to develop, we need to leave the flowers intact.

Instead of perpetuating consumerist habits and appeasing exploitative tendencies through plant harvest and extraction, the story of ghost pipe invites us to re-engage in mutualism and an ecosystem-level approach to health. ō

NOTES

1 Mycoheterotrophy is common in vascular plants, with nearly 10% of them engaging in fungal relationships in early germination and growth stages (Leake and Cameron 2010). Fungal partnerships are key for initial seed germination and early nutrient uptake, and many plants benefit from mutual mycorrhizal relationships. Ghost pipe is a full mycoheterotroph, utilizing carbon from the basidiomycete Russula brevipes (Trudell, Rygiewicz, and Edmonds 2003) without recycling it to the fungus.

2 Naturalists have shared this observation informally in forums, social media, and personal communications.

3 “Cheaters don't always win: Species that work together do better.” Science Daily, Oct. 19, 2020.

REFERENCES

Bidartondo, M.I. (2005) ‘The evolutionary ecology of myco-heterotrophy’, New Phytologist, 167(2), p335-52.

Felter, H.W., JU Lloyd J.U. (1905) King’s American Dispensatory, 19 ed, Ohio Valley Co., Cincinnati, OH.

Google Trends, 2022, Explore: ghost pipe, viewed 8/15/22.

Klooster, M.R., Culley, T.M. (2009) ‘Comparative analysis of the reproductive ecology of Monotropa and Monotropsis: Two mycoheterotrophic genera in the Monotropoideae (Ericaceae)’, American Journal of Botany, 96 (7), p1337-47.

Leake, J.R., (1994) ‘Tansley Review No. 69: the biology of mycoheterotrophic (‘saprophytic’) plants’, New Phytologist, (127), p171-216.

Leake, J.R., McKendrick, S.L., Bidartondo, M., Read, D.J. (2004) ‘Symbiotic germination and development of the myco-heterotroph Monotropa hypopitys in nature and its requirement for locally distributed Tricholoma spp’, New Phytologist,163(2), p405-423.

Leake, J.R., Cameron D. (2010) ‘Physiological ecology of mycoheterotrophy’, New Phytologist, 185(3), p601-605.

‘Monotropa in convulsions’, 1881, Eclectic Medical Journal, 41(5), p231-232.

NatureServe, 2022, ‘Monotropa uniflora’, NatureServe Explorer, viewed Aug 5.

Trudell, S.A., Rygiewicz, P.T., Edmonds, R.L. (2003) ‘Nitrogen and carbon stable isotope abundances support the myco-heterotrophic nature and host-specificity of certain achlorophyllous plants.’ New Phytologist, 160, 391-401 p.

RENEE DAVIS is a mycological systems designer addressing topics in mycology, ethnobotany, conservation, and human-nature relationships. Her has been published in Pulse: Voices from the Heart of Medicine, Journal of the American Herbalists Guild, BMC Complementary, Alternative Medicine, and other publications. Originally from New York, she currently resides in Olympia, WA.

Add new comment