'Soliciting Votes,' by William Hogarth 1

SYRACUSE, NEW YORK — It's mid-term election time in the US. I am on the roster to go out canvassing again and this time I'm doing for my Democratic congressman here in Upstate New York, Dan Maffei, who's in a hard-fought race for re-election against his Republican opponent, John Katko.

I walk door-to-door in a working-class neighborhood of Syracuse and try to encourage and inform voters identified as leaning toward my candidate, or who are undecided. This is retail politics, something I have not been able to do in the decades I wrote for The Post-Standard, the daily newspaper in town. Now retired, I can display my political allegiances proudly: stake a lawn sign, declare myself a joyful Democrat, do some of the grunt work which, I am convinced, helps to move the democratic process forward.

Clinton said this election is about building out the economy from the middle, with a prosperous middle class. Anything else is just “background noise.”

It helps to be in one of a score of tightly-contested House seats, out of 435 across the country. It means we may not have the strongest candidate, but there is a glamorous payoff. The other day, Vice President Joe Biden landed at Hancock International Airport for an inspirational stopover. On Friday, former president Bill Clinton dropped in. A visit from these eminences enlivened the political season, and they appeared to thrive on the love they received. Biden may have been fueled for a potential presidential bid in 2016. He’s getting old, though he looked to be in excellent shape. His reputation for delphic malaprops extended to a remark about the American spirit during his uplifting, 25-minute oration. “If we build a mousetrap,” said Biden, “they will come.”

The Bill & Joe show rolls into Syracuse. Many Democrat candidates were distancing themselves from Barach Obama, who, to some, is in pollitical quarantine.

As for Clinton, the beguiling superstar strode onstage, relaxed and immaculate under a mane of white hair. He was chewing gum — apparently to soothe a throat overtaxed from service to other candidates on the road. Clinton started out hoarse, but his voice cleared as he warmed to his subject, and he looked less weary and wrinkled than he did in recent media coverage. He reminded us he isn’t running for anything — as though we might forget his wife is all but the anointed Democratic candidate for president in 2016 — and that this election is about building out the economy from the middle, with a prosperous middle class. This is what our guy wants — instead of sending most of the rewards to the top — which is more likely to happen if the other guy wins. That’s what this election is about, Clinton said. Anything else is just “background noise.”

Meanwhile, my candidate Dan Maffei seems focused on getting and spending money more than anything else. A half-dozen times a day, I get breathless emails from his campaign. There are notes from other Democrats — national campaign doyenne Debbie Wasserman Schultz, former House speaker Nancy Pelosi, former Labor secretary Robert Reich. “It’s down to the wire!" . . . “It’s scary!” . . . “We’re begging!”

When you go through your spiel, there's a civil conversation. On the whole, I find it a satisfying way to be politically engaged.

It’s no more fun reading these stinkers than it must be to write them, but it is fun to canvass door-to-door. Yes, it takes time, and there are frustrations — like finding half the people on your list not home. Or stumbling on the occasional Tea Party Republican. “Don’t bother trying to convince me,” said the balding man in a blue work shirt, with a grin that was half a leer. I kidded him back: ”You mean you really want to send another Republican to the House to keep gumming up the works?” His grin widened and his eyes glittered as he replied: “That’s what we do!” Democratic fool that I am, I reflexively blurted out: “Well, make sure to vote!”

The fun part is seeing how people live: to climb on their porch, admire their landscaping and patio furniture, take note of the children’s toys and whatnot lying about. You may even get a glimpse through a window.

'Soliciting Votes,' by William Hogarth 2

Then there are the conversations. I was relieved to discover that, by and large, folks treat canvassers with some respect — particularly if you tell them you are a volunteer. The list is supposed to be limited to Democrats and independents, so when you go through your spiel, there's a civil conversation. Occasionally, you may influence a vote. On the whole, I find it a satisfying way to be politically engaged.

However, I have soured on giving money to my candidate. I know he needs the dough, and that I should contribute what I can. For me it is literally an article of faith. We Unitarian-Universalists covenant to promote “the use of the democratic process.” That surely includes giving money, if I can afford it.

Money may win a candidate’s attention, even loyalty and obedience, but it can’t win an election.

But I cannot bear those relentless, intrusive, money-grubbing emails. I am put off by the robotic notes. ("Incredible, Fred. We couldn’t have met our three-month fund-raising goal without you." Oh, really?) And I am discouraged by what those campaign dollars help pay for: political advertisements so corrosively negative that they tarnish both candidates. Recently I sat with an old friend who put her TV on mute when the political ads came on, shaking her head and muttering darkly about the current political state of affairs.

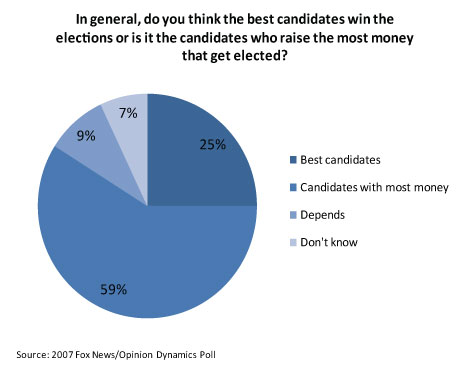

Money has trapped America’s political process in a spiraling frenzy of getting and spending. The campaign becomes a frantic nightmare of catch-up, as noted in those desperate-sounding emails. One side’s excess is reason enough for the other side to abandon principle and substance and focus almost exclusively on the race to match the other side, dollar for dollar, attack ad for attack ad.

For most of the nation’s history, corporate political contributions were frowned on, if not illegal. There were efforts to limit encroachments in the 1970s, after Watergate — financial shenanigans that seem quaint today. In recent years, the reforms of McCain-Feingold (2002) were a step forward — until the U.S. Supreme Court’s startling Citizens United ruling (2010) removed virtually all restraints on money in politics.

Some call for a constitutional amendment to reverse Citizens United, with its baffling assertions that money is speech and corporations are persons. These twist of semantics, legalism and politics will be hard to untangle. There is a better, easier way to get at the dangerous excesses in campaign financing that insult and abuse our democracy.

The solution is a legislative one — a step back to the future. Public financing of campaigns is a decades-old idea that has flowed and ebbed, but deserves to rise again. It has been adopted in Maine, New York City and a few other precincts, though not in Congress. Public funding of presidential races has gone off the rails, with candidates on both sides rejecting the limitations in their lust for corporate dollars. In an era of multi-billion-dollar national campaigns, with no limits in sight, the drive for public financing gains a new urgency.

There is no procedural or constitutional obstacle to a comprehensive, universal public alternative. Candidates who agree to limits will be provided generous funds from us taxpayers — donations that are fully consistent with our democratic obligation as citizens. Candidates can spend their time promoting themselves rather than playing catch-up and lobbing attack and counterattack ads. At least there will be fewer ads, negative or otherwise, and more opportunity for substance and retail politics.

"When big money loses, the people generally win." 3

Candidates are entitled to opt out of public financing, and their opponents also are entitled to remind voters which candidate spurned their offer — for a better offer from the special interests.

Money may win a candidate’s attention, even loyalty and obedience, but it can’t win an election. Whatever else his shortcomings, Mitt Romney did not lack for cash in 2012. With a citizen mandate in place to limit the role of money in politics, those who continue to spend disproportionately will quickly stand out. They might well be shunned, a common social practice in the time of the founding fathers, but a practice too little seen these days.

In a happier future, the big spenders would suffer politically for their profligacy. In that happier future, they might lose. When big money loses, the people generally win.

Given the chance, I will joyfully check a box on both my national and state tax returns to allot a modest sum to a public campaign fund. I know the money will flow fairly to my favorite candidates, as well as others. That’s OK. My spirit soars at the prospect of my dollars, combined with many others, are restoring balance and proportion to our democratic election process.

Chart courtesy of Center for State Innovation. 4

RELATED LINKS

Public Financing of Campaigns: An Overview (survey)

'Time for public financing of elections' (article)

'Power in the hands of voters, not donors' (organization statement)

Public Funding of Presidential Elections (brochure: 1996, updated April 2014). In April 3, 2014, President Obama signed legislation that will end public funding of national nominating conventions. This brochure to read in tandem with the new law, Public Law 113-94.

Public Law 113-94 (law)

FRED FISKE, an independent journalist and composer, spent his career in journalism, mostly writing editorials for The Post-Standard newspaper in Syracuse, New York. He majored in history and literature at Harvard and received his masters from the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism. He grew up in a foreign service family, living in Bangladesh, Germany, Congo and Iceland.

Add new comment