Andrew Rucklidge, A Bright Room Scanned Darkly

Christopher Cutts Gallery

21 Morrow Avenue, Toronto

To December 23

“Art, has something to do with the achievement of stillness in the midst of chaos . . . an arrest of attention in the midst of distraction.”

— Saul Bellow

As a boy, Andrew Rucklidge was fascinated by wooden cases of rock samples that his geologist father would bring back from faraway places like Greenland and Spitzbergen, telling stories of “getting stuck in the ice, fishing for salmon with dynamite.”1 As a young man he went to see for himself, living for a few years in the Yukon, cultivating a taste for wild rivers and big skies. After he became a painter he continued to be drawn to the harsh, otherworldly magnificence of the far North.

Now, at 49, he goes on annual whitewater canoe trips with his wife and children and spends much of the summer out in the islands of Georgian Bay where he has a seasonal studio. He completed an MA in Fine Art at Chelsea College of Art in London in 2003 and he’s been working as an artist and exhibiting internationally since then, fourteen years. He currently teaches at the Ontario College of Art and Design in Toronto, including a course in painting methods called “Contemporary Alchemy”.

It’s kind of like an elixir that I am making every summer.

Rucklidge grew up with a strong family orientation to chemistry, physics and minerals, giving him an extremely comprehensive understanding of his raw materials — rare for an artist. His methods, and the works that emerge from his process, have something in common with ancient alchemy’s convergence between science and poetics, chemistry and metaphysics.

“I make the oil that I use, up north in the summer,” says Rucklidge, “It’s a linseed oil and its sun-thickened. I place it out in covered metallic plates and it hangs out for a good fourteen days. So it’s as if it gets cured of all its unfortunate characteristics by the sun and the oxygen. It becomes a different kind of painting medium that dries a lot more quickly, and it allows you to do certain things with oil, to work with a more liquid oil, that you can’t really do, normally. It’s kind of like an elixir that I am making every summer.”

Rucklidge, Andrew. A bright room scanned darkly. 2017, 52 x 60 inches, oil on canvas on toned gesso.

The landscapes have a texture that is rare in contemporary painting, imbued with inner luminosity and liquidity. Rucklidge combines egg tempera and metallic pigments in their pure form, grinding them into his sun-cured linseed oil. “That goes back to the Renaissance. It’s an old school way of getting motivated to paint — and excited about painting — by actually grinding your own colours.”

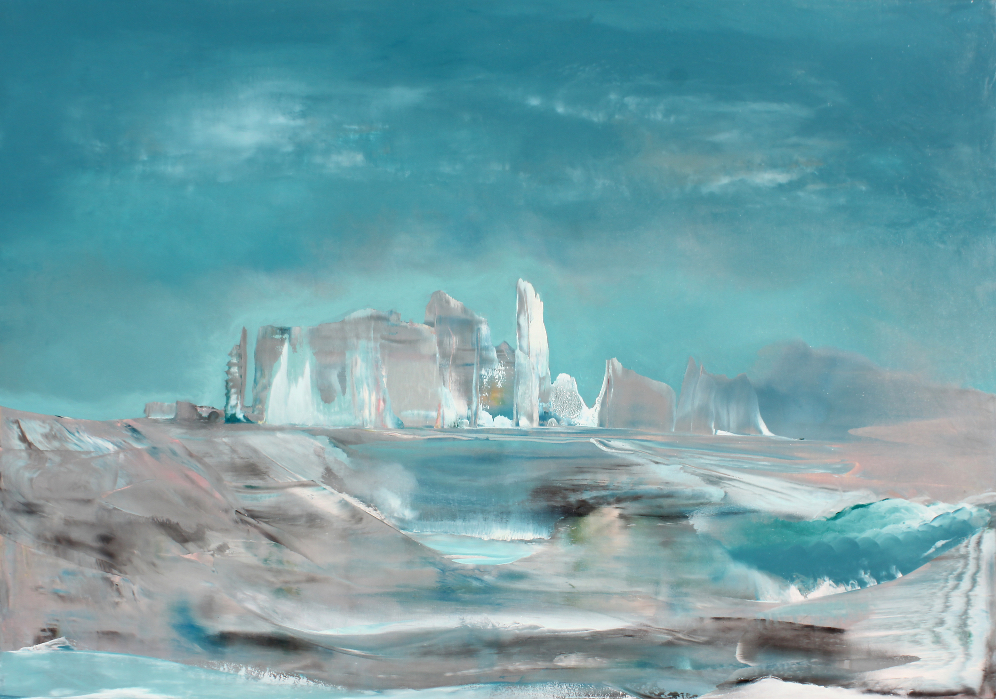

Rucklidge's paintings appear to imitate the geological world, effects that are achieved in part through his understanding of chemistry. “I think of pigments as parts of minerals. I’m very aware of the chemistry, of the elements that make up the pigments. Cobalts. Different oxides, different colours . . . I can still remember childhood chemistry experiments and recall where the pigments are located on the periodic table. I’m never confused when I use pigments in different mediums. I know the mineral content, and how they relate to each other in the same painting.”2 In the painting, “The Wasting of a Pingo”, for example, the bright white flecks in a dark rock face are titanium oxide pigment in pure form, which has been deliberately left unmixed in the surface of the paint, creating the effect of debris on the land.

Rucklidge, Andrew. The Wasting of a Pingo. 2017, 38 x 54 inches, oil and egg tempera on toned gessoed panel.

He has an alchemist’s perspective on the relationship between the materials of the earth and the images he creates, between the literal and the metaphorical. “There is a one-to-one mapping between the pigment extracted from the earth — and its resemblance to the land — once it has been mixed with other pigments. If you allow the paint to reach equilibrium, i.e., get it to its resting point, then it will look like a place, a rock formation, something out of the natural world.”3

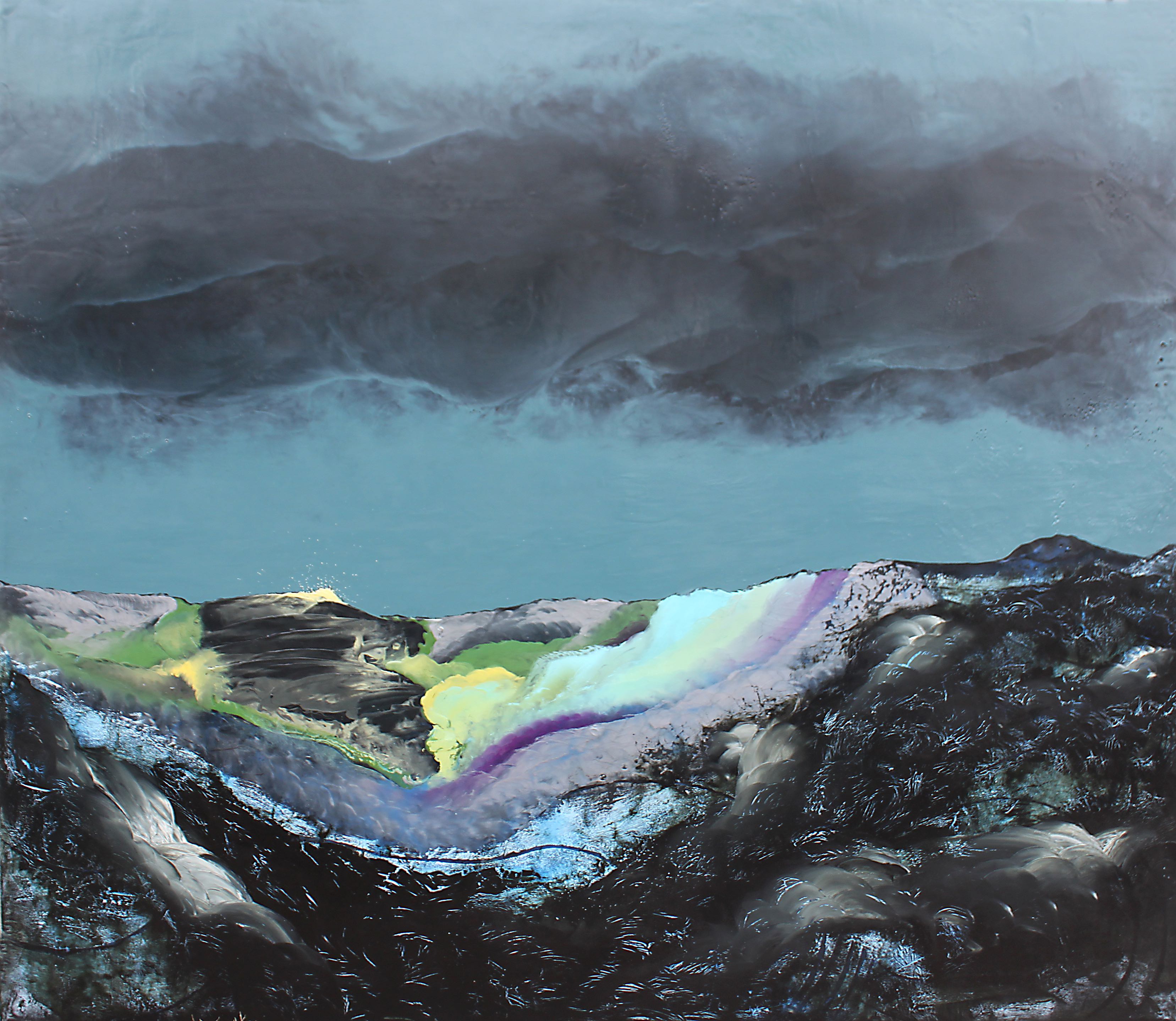

Several of the paintings are dark, such as “Resistant Beds”, which is filled with foreboding. Knowing that the subject is the Arctic, it is possible to read eco-apocalypse into it. This painting is big and astonishing, a black and fiery landscape with a molten transformation in the middle ground, and a yellow-hot mountain peak in the distance under glowering, storm-threatening grey-black clouds. Rucklidge is uncomfortable with the word ‘apocalyptic’, and says he prefers to leaves it to us to encounter the work in our own way. “People can think for themselves . . . Maybe because I am painting all the time — and thinking about colour — to me as a painter black is just a colour.”

Rucklidge, Andrew. Resistant Beds. 2017, 52 x 60 inches, encaustic and oil on toned gessoed panel.

Black may be just a colour, and ice merely a form of water, but compassion is palpable in Rucklidge’s work. When he speaks of the land and people his voice reveals a lively mind firing on all cylinders. “One of the things I was really trying to paint is not just the atmosphere but also the disappearing glacier, or edge — the permafrost. ‘The Wasting of a Pingo’ has to do with permafrost. You can argue pretty strongly right now that ice edges at the edge of the continent are less stable, and less usable. I’m mindful of the fact that it does affect the people that live up there, their way of life, and hunting.”

What is a pingo, you may ask. A pingo, also called a hydrolaccolith, is a hill of earth-covered ice found in the Arctic and subarctic. For the Inuit, the shrinking or wasting of a pingo is a sign, on the horizon, of melting permafrost.

It’s a deep aesthetic experience of the land . . . a respect for places where it is difficult to live.

There is a feeling in these landscapes of receding ice and the lost habitat of wild creatures and the people who coexist with them in the life zone between Arctic land, ice and sea. Rucklidge paints the liminal transition zone of the shifting, softening, unstable ice edge in our time. The massive ice forms in these paintings seem to exist in a fluid transition between water and ice. If we forget the shadow of global heating as we are drawn into a reverie with these paintings, the elegiac tone of titles like “The Last Sheets” conjures up convulsions of collapsing ice shelves and pack ice melting beneath the feet of white bears.

When I asked Rucklidge if he was trying to express something metaphysical in his paintings, he asked what I meant. I said there was a tradition in modern art, not just ancient art but perhaps all art — and in our time, from Kandinsky to Pollock to Jack Chambers — of attempting to express transpersonal meaning through art. Another way of putting it is that there is a certain longing in the artist to depict the reality behind the veil of the physical world; this is painting as a portal, or painting as a window through to the unseen; or, the inexpressible divine, something you can’t put into words. Rucklidge said he could agree with all that, but that he is inclined to express it in terms of empathy. “If there is anything spiritual about it, it’s a deep aesthetic experience of the land. That probably comes from growing up with a geologist, and the actual minutiae of it, the detail of it . . . a respect for places where it is difficult to live and the kind of work ethic that people need to have to survive up there.”

Rucklidge, Andrew. The Last Sheets. 2017, 38 x 54 inches, oil and egg tempera on toned gessoed panel.

The painters that Rucklidge mentions as being important to him all make sense: the drive toward chaos of Francis Bacon, as well as the meditative intensity and subtle colour sense of David Milne. He also mentions respect for Lawren Harris, the Group of Seven (a group of Canadian landscape painters from 1920 to 1933), and American Sublime painters such as Bierstadt. Rucklidge’s work is complementary to those schools but also radically different, and for me it’s a welcome antidote to the formal towering symmetry of Harris’ or Doris McCarthy’s stylized icebergs. Rucklidge’s preoccupation with natural phenomena — and his uncanny translation of vast natural forces into paintings that are enormously moving — reminds me of Paterson Ewen’s work. Evident are the atmospheric echoes of Turner and the moody landscapes of Kaspar David Friedrich — though these are possibly just personal associations.

This show also includes works in other styles and techniques which are not Arctic landscapes, such as “A bright room scanned darkly”, an enigmatic and arresting painting that could be a shadowy room of ice, water and light on another planet. Incidentally, the concept for the show came from experiments manipulating his northern landscape paintings in a scanner. The scanned works are conceptually interesting, technically fascinating, and have their own integrity. Yet, it is Rucklidge’s unique vision of the Arctic land and icescapes that, to my mind, are remarkable, timely and timeless. ≈©

NOTES

1. Andrew Rucklidge in conversation with Nick Purdon, in the book, Andrew Rucklidge Paintings, 2005-2007, published by Andrew Rucklidge and Christopher Cutts Gallery.

2. Purdon, ibid.

3. Purdon, ibid.

All quotations are from Andrew Rucklidge in conversation with Chris Lowry, Nov. 28 2017, except as footnoted.

Rucklidge, Andrew. Slope Retreat. 2017, 44 x 46 inches, oil and egg tempera on toned gessored panel.

CHRIS LOWRY is a writer and media producer, some of whose work is on artists, including the film Chambers: Tracks and Gestures on painter Jack Chambers. His current project is a documentary about the life of the influential scholar, art critic and educator Ross Woodman.

Comments

So enjoyed this story on

So enjoyed this story on Rucklidge. Making his own paints from the land, such involvement with his expression. Anong Beam on Manitoulin Island is now making and selling paint from local pigments. BEAM paints.

I found both Rucklidge's work

I found both Rucklidge's work and your insights really stimulating. I'd like to see his work in the flesh.

Can't wait to see this in

Can't wait to see this in person. Great review and great issue of The Journal of Wild Culture!

Really interesting work from

Really interesting work from the celebrated Mr Ruck, especially "The Last Sheets". Evocatively representative landscapes and yet acid-y. And for me, a new word: pingo.

Thanks!

Beautifully written Chris

Beautifully written, Chris. Your well-chosen words drag me in and along with you as you describe and inquire.

Thanks for iwriting about

Thanks for writing about this stunning work!

Add new comment