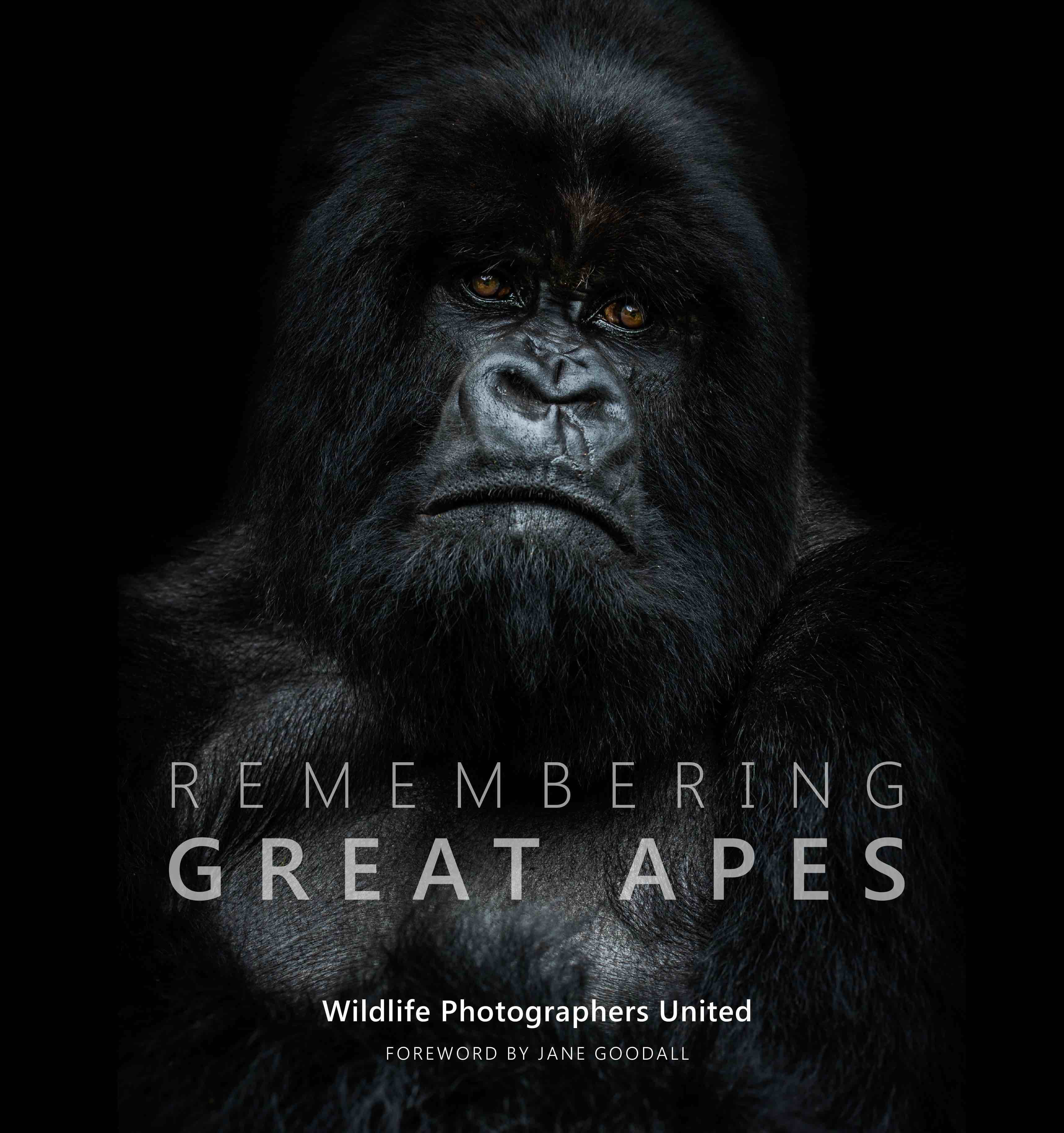

Inset of photograph by Billy Dodson. Volcanoes National Park, Rwanda, featured in Remembering Great Apes.

Do you remember the moment when you had your first significant learning experience with wildlife photography?

My first proper wildlife photography trip, to the Masai Mara in 2010, was with the couple Jonathan and Angela Scott — both who have won the coveted title of Wildlife Photographer of the Year. Their work was so inspiring, and their message about conservation so eye-opening, that I resolved when I returned from that safari to learn how to use my camera properly to start using photography to raise awareness.

As you have continued in this career, is there one idea — perhaps inspiring, perhaps disturbing — that keeps coming back to you in relation to your close proximity to the animal world?

Well, it isn’t an idea, but what disturbed me was seeing a poached elephant who had just died that morning — from a poachers arrow. Witnessing this brought me to tears and provoked me to start the Remembering Wildlife series. For the first time I saw face to face the consequence of the demand for ivory. It was horrific.

Marcus Westburg. Kahuzi-Biega National Park, DRC.

The natural world has its own ethical system, much different than ours (or maybe not so much). Can you tell us what you have learned through the witnessing of violence, death, and the survival instinct in the animal world that has informed your worldview?

In the majority of cases, animals are driven purely by instinctive needs, whether to eat, breed and pass on their genes, or simply to survive. Unlike humans, there is no greed, jealously or maliciousness in their actions. As a result, I find it very refreshing to spend time with wildlife. However, chimpanzees — being closest to humans in DNA terms — are also in the majority of cases very similar to humans in their behaviours.

Andy Biggs. Volcanoes National Park, Rwanda.

With this new book, Remembering Great Apes, there is a focus on the animal species that is, as you've just said, closer to humans than any other. How has this affected you?

Looking into the eyes of an ape sends a shiver down your spine. It's like looking into the eyes of a fellow human — suddenly you realise how accountable we are for their future.

Remembering Wildlife is the organization you founded that funds wildlife protection campaigns through the sale of books. What have these campaigns accomplished so far, and what have you learned in this conservation process?

So far we’ve distributed £350,000 [$453,000 US] from the first two books, Remembering Rhinos and Remembering Elephants, which has supported 15 projects in 13 countries. This has paid for everything from veterinary care for the victims of poaching to anti-poaching patrols, including aerial patrols and sniffer dogs. It's also supported researchers, paid for camera traps to keep an eye on relocated rhinos, contributed to relocations and helped fund the building of schools in local communities surrounding game reserves. What I've learned is that conservation requires holistic approaches, and there are many of these that need support. A partnership with the Born Free Foundation over the past three years has helped me to learn how to identify effective projects and ensure that our funds have been used wisely.

Jami Tarris. Kalimantan, Borneo.

Margot Raggett. Mahale Mountains National Park, Tanzania.

Is there one particular success you can point to?

As the work of conservation teams on the ground is often an on-going and unending war, it is sometimes difficult to pin down successes that we can claim. I am particularly proud that the anti-poaching patrols we helped to fund during the Mana Pools wet season last year reduced the poaching incidents to zero — compared to 10 elephant deaths, at least, the year before. Often I think back to that first poor poached elephant and think: if we can stop another animal from suffering that same fate then that makes it all worth it.

Tom Way. Sumatra.

How do you gauge and negotiate risk and danger on the job as a wildlife photographer?

Honestly, there is no danger in the type of wildlife photography I do. I’m not doing undercover work, just photographing most often in protected game reserves.

For amateur photographers interested in this area, are there any procedural (getting the right shot) and technical photographic tips you can share?

Learn how to use your camera and understand things like the importance of getting the right shutter speed. When you are in the field and something special happens you don’t want to miss the shot because you're fiddling with your camera!

More information on the book and supporting Remembering Wildlife's conservation campaigns.

MARGOT RAGGETT is a wildlife and travel photographer who works in Kenya, Masai Mara, Tanzania, Kefalonia, Bhutan and the UK, and is the founding director of Remembering Wildlife. margotraggettphotography.com

Other photographers from WILDLIFE PHOTOGRAPHERS UNITED featured on these pages

Andy Biggs — andybiggs.com

Billy Dodson — billydodson.com

Jami Tarris — jamitarris.com

Tom Way — tomwayphotography.co.uk

Marcus Westerberg — lifethroughalens.com

Add new comment