HSITORICAL CONTEXT: AT THE CROSSROADS OF EMPIRES

These photographs were shot on a solo overland trip to India from Europe in the autumn of 1977. No one knew it yet, but it was the end of a sixty-year run of unbroken peace in Afghanistan. In April of 1978 there would be a military coup. A group of local Marxists, much to the dismay of Moscow and most Afghans, would assassinate the president, take over the country and suddenly attempt to radically change relations between peasants and landowners, men and women. For the hippies on the Magic Bus travelling overland from Amsterdam toward the beaches of south India, there was no hint of that in the air. Roadside flowers and jingling bells on horse-drawn buggies gave the sense, to a foreigner, of being caught in a gentle medieval time warp.

Sir William Elphinstone’s retinue of 16,500 were slaughtered without mercy in the winter snows as they tried to retreat from Kabul.

Sixty years of peace, in a country that had been soaked in bloodshed for millennia. When the Russians began their occupation of the country in 1979, the people of Afghanistan had not been conquered or colonized since the decline of the Moghul Empire in the 1600s. During those three centuries, every Afghan ruler was either deposed or assassinated. President Daoud, assassinated in 1978, had also come to power in a coup.

Kabul today, photograph by Steve McCurry. ≈

Afghanistan was a crossroads for empires, tribal rivalries and the riches of the Orient. Alexander the Great, Ghengis Khan and Babur all tried to tame it. Some say that the blue eyes among the mountain peoples came from Alexander’s Greek soldiers. The land is strategically important and resource rich, yet virtually unconquerable. The only near-universal trait common to all Afghans is a fierce territoriality rooted in feudal, clan and ethnic loyalties, nurtured in communities isolated by mountainous terrain. Even Islam is not unified among Afghans, as Sunni and Shi’a versions of truth face off across mountain passes with mistrust and mutual contempt.

The region was a prize, a buffer zone in the Great Game played by the imperial powers of Britain and Russia. During the course of three bitter Anglo-Afghan wars, the British learned a lot about Afghan vengeance. The mountain passes east of Kabul offered many Englishmen their last glimpse of hell on earth, as when Sir William Elphinstone’s retinue of 16,500 were slaughtered without mercy in the winter snows as they tried to retreat from Kabul across the Khyber Pass in 1842.

The Khyber Pass, 1977.

Since the end of the third Anglo-Afghan War and the signing of the Treaty of Rawalpindi with Britain in 1919, foreigners had stopped trying to conquer this region. From his urban base, King Amanullah Khan made efforts to move the country into the 20th century, but in the rugged, roadless provinces traditional life changed little from one century to the next. After World War II it became a chessboard for the Soviets and the Americans. The CIA began working in Afghanistan forty years before they backed the mujahidin against the Russians. James A. Michener, who was there in ’46, called it “an exciting, violent, provocative place… one of the world’s great cauldrons." By 1977 there were cars, trucks and TVs, but nine out of ten Afghans were not literate and lived, both culturally and geographically, beyond the reach of modernity. . .

I travelled then in a state of half-informed curiosity, mindful of the intricate web of custom that separated me from the local people, unaware of the political unrest beneath the picturesque surface. These are a foreigner’s naïve impressions of everyday life forty years ago, when Afghanistan was at peace.

This account is adapted from journals and letters written in the winter of 1977-78.

Taking a horse and buggy taxi to the market, Herat.

DECEMBER 1977

I get on the minibus in Kabul thinking that I’m the only westerner on the bus going north into the December snow, but as I’m putting my pack in the overhead rack I meet a French couple who are, oddly, travelling with a cat. Their names are Philippe and Catherine. We all agree that we’re lucky to find a bus going to Bamiyan, and we hope the roads are passable.

They are surprised and relieved when I speak French. Few francophones travel the Magic Bus route overland to India. So these two are rare birds, quite magnificent. I am fascinated by Catherine — her fine bones, her delicate beauty, her sharp intelligence. Philippe, who adores her, is a tall handsome dark-eyed Frenchman with a great red beard. They are open, curious, and we laugh a lot.

Hazara man in a truck in the Hindu Kush mountains, winter 1977.

On the long, bumpy bus trip they tell me their story. They had been travelling to India in a VW camper with their cat, Titöi. A few weeks earlier, in eastern Iran, they had a road accident that wrecked their van. Driving at night, they had hit and killed a donkey. They were arrested, forced to pay bribes to get out, had to pay compensation for the dead donkey, and now they are travelling on as backpackers, with this amazing cat. She’s a cross between a wild north African mountain cat and a domesticated Morroccan town cat. In Bamiyan town, Titöi attracts a lot of attention. We keep her close. We joke, half seriously, that someone might steal her for her fine fur and perhaps roast her on a spit.

From the village the famous cliffs and their great statues can be seen in the distance. Astonishing, lonely, seeming so displaced, so far away from any living Buddhists. Delightful to climb and photograph, and to imagine a vast colony of monks living in these austere sandstone cells dug out of the cliff, in winters like this one that is beginning to bite deep into our flesh.

They stripped off their clothes and one of the blonde Nordic girls dove in first. Local men in the hills above were watching them, and were deeply offended.

In Kabul I heard about a group of lakes called Band-e Amir 75 kilometres from Bamiyan that are rumoured to be exquisitely beautiful, but everyone I spoke to told me it would be impossible to get to them at this time of year. Catherine and Philippe are also interested in going, so we ask around. We get a different answer from each person, which is not uncommon here.

During that conversation in the Kabul hostel, I heard another story, a cautionary tale. Some European backpackers were visiting the lakes of Band-e Amir. It was a hot summer day, and they decided to go for a swim. They stripped off all their clothes and one of the blonde Nordic girls dove in first. Local men in the hills above were watching them, and were deeply offended at sight of a naked woman swimming in the sacred lake. A shot rang out from the hills. One of the outraged tribesmen had raised his vintage bolt-action Lee-Enfield rifle, a relic from the third Anglo-Afghan war, and killed the swimmer with a single shot to the head. Execution or murder, depending on which side of the gun you are on. So, say the travellers, try not to offend the locals. When I start to repeat this tale to my new friends, it turns out they have already heard it.

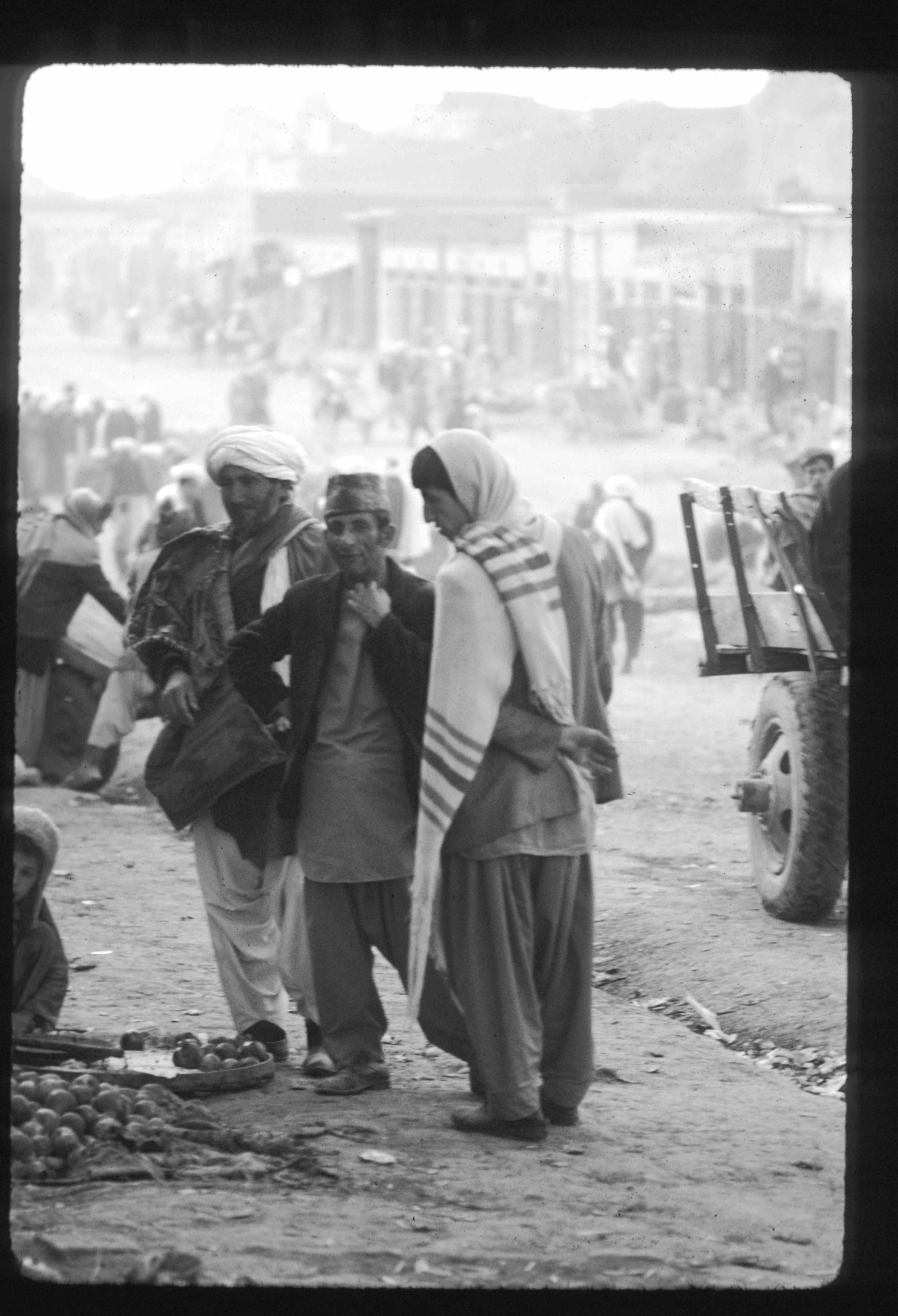

Men doing business in the market.

After two days visiting the caves and the giant Buddhas, we agree to attempt to go up into the mountains to visit the lakes. We may never be back this way again, and we figure it’s worth a try. Early on a cold, grey morning the four of us book seats on a small local transport truck and set off.

It is a strange trip. We ride up into the mountains in a small open truck packed to the gills with Afghan people. After couple of hours, the truck leaves us at a mud and thatch tea house sitting alone in the middle of nowhere along what they call a road, about a hundred yards from the path leading to Band-e Amir. We stop to eat some soup and bread with tea, with two very excited Afghan men dancing around us and talking. They are in an incredible state of agitation, first because they have guests in the middle of December, crazy foreigners, and second, especially, because one of us is female. Afghan men must pay about $2000 bride-price for a wife, over twenty times the average annual income, and they suspect infidel Western women of being prostitutes, so you can imagine their delight in this isolated situation. Besides all this, one of them really lost his marbles long ago, and laughs continuously with contorted expressions on his face. We’re a little uncomfortable to say the least.

The half-sane one of the pair explains that there are no people at Band-e Amir and we must stay the night with them. We want to get out of there, though. It’s only 11:30 in the morning and we figure it will take only a few hours to walk to the lakes. Seeing that we are determined to leave, the least-crazed of the pair shows us the way to the road, and we head off into the barren mountain landscape, stretching white and empty all around, to the sound of the fool’s bizarre laughter, not really knowing what we will find on the other side. As we leave we also notice the dark form of a lone man moving off into the mountains in another direction, completing the feeling of isolation that weighs down on us. But I am glad to be on the way; it feels very good to be hiking in the mountains again, not knowing what is ahead and being comfortable with that.

A father and daughter visit a cobbler in his workshop.

The walk is good, though the sky begins to cloud over again after about an hour. The rutted dirt road is easily visible under a light cover of snow, and in a couple of hours we see the first blue form of a lake between the mountains ahead. It is astonishingly beautiful, and we are grateful to each other.

After another hour’s hike over gentle slopes we reach the valley. We’re relieved to see people and villages here and there through the powdery snow which has been falling thickly during our descent. Far off, a figure the trudges toward us in the deepening powder snow. As we approach each other, we see that it’s a child, a handsome boy in a sky-blue turban and grey tunic. In broken English he introduces himself as Hussein, and tells us that his father has sent him to meet us, and he offers to take us to the village. Crossing a bridge we meet two friendly men who are fishing for small trout in the stream. One of them, Hussein’s father, tells us that the boy will take us to the village and the chai khana of the village headman, where we can have tea and arrange place to stay. Hussein tells us that the last tourists of the season left this isolated valley weeks ago.

Hussein is ten years old. He knows a lot of English words and can form simple sentences. He says he learned his English from summer travellers. He becomes our guide, interpreter and storyteller. We persuade him, his father and brother to remain in the summer village for a few more days for our sake, to look after these three mad farangi who have appeared unarmed amid the first heavy snowstorm of the winter, to see the holy lakes.

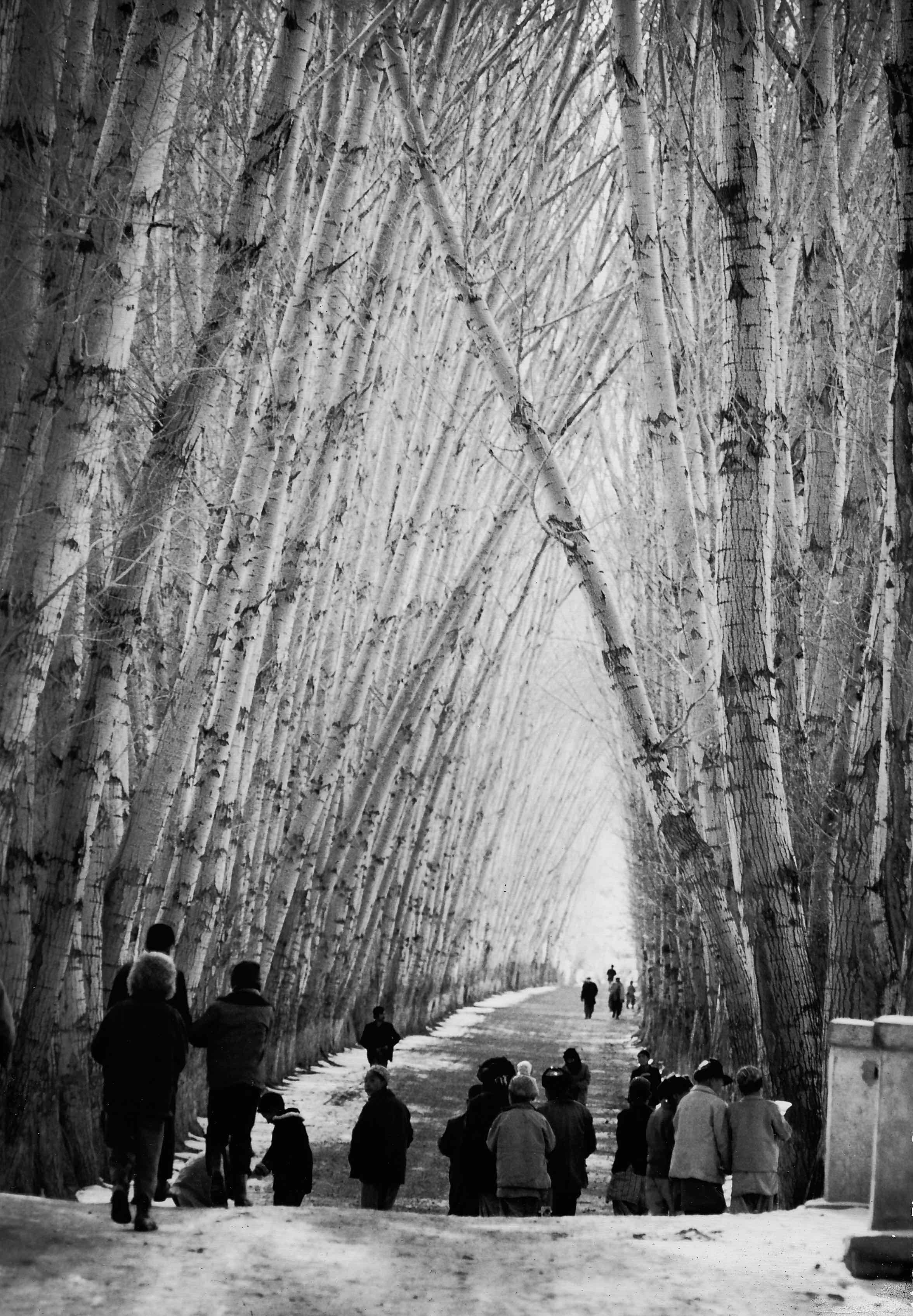

An avenue of poplars leading to a mosque in Bamiyan.

The seven blue lakes of Band-e Amir are like a string of sapphires, emeralds and lapis lazuli embedded in the treeless Hindu Kush mountains, separated by limestone dams and connected by waterfalls. With great seriousness and authority, Hussein tells us their creation story. They were made by Ali, fourth Caliph of the Musselmans, the cousin of the Prophet Mohammed who founded the Shi’a faith. As the local story goes, he came here and created the lakes by making dams out of cheese, which grew into white stone walls. The cascading overflow continued in a chain of seven magic lakes, full of beautiful fishes. The lakes are said to have peace-giving properties for troubled spirits who swim in the waters. Thinking about the infidel swimmer and the vigilante’s bullet, I say nothing to Hussein.

With shining eyes Hussein continues his story. Ali came to the valley of Band-i-Amir to slay the dragon which terrorized the people. It demanded of the village seven fatted animals and one young virgin every day. The dragon was unfortunately not a Muslim, so when Ali demanded that it recognize the One True God, it refused and lost its head to his great scimitar, Zulfikar. Then Ali blessed the land with the divine lakes where men lived in peace.

I tell Hussein that the Christians also had a heroic saint long ago who slayed a dragon. Hussein nods gravely. Are you Christian? he asks. We hesitate, and I decide that the simplest answer is yes.

A view of one of the seven blue lakes of Band-e Amir.

Hussein’s people here in the mountains are Hazara, quite distinct from most the Afghans I have encountered so far. They’re part of the Shi’a religious minority which dominates in neighboring Iran, and their tribal traditions are akin to the Mongols of the central Asian steppes. The Hazara have a long history of oppression by the Pashtun, Sunni majority.

The next morning when we emerge from our sleeping bags on the floor of the dark mud house and step outside, the village and surrounding mountains are blanketed in deep powder snow that fell all through the night, and there is a thick fog hiding the landscape. Our hosts offer to take us out on horseback to see some of the lakes for a couple of hours today. While we wait for the horses, I sit on a stone bridge over the creek writing in my journal. The mountains gradually emerge from the mist, the sun breaks through over the lakes, and it is glorious. The air isn’t too cold during the day here. In addition to my old sweater and down vest I have Afghani wool gloves, socks, and a broad shawl around my shoulders, bought in the Kabul bazaar.

Our first glimpse of Band-e Amir, with new snow.

We stay two nights at Band-e Amir, exploring during the day and spending the evenings talking in the warm little mud room. A couple of the boys speak English well, as there are a lot of tourists here in the summer. We eat and sleep on the floor in the same room with five Afghani men. We feel safe and respected, in keeping with the deep local traditions of hospitality. Of course it helps that we are paying guests. In the evening the mud building has very little light from small windows, but it is warm. The food and conversation are simple. We live as they do, on their terms. These men meet a lot of tourists, but they never spend hours with them in winter, in this den-like space with nowhere else to go. They seem to be hearing for the first time our strange stories of a world where men pay nothing for a wife, but can, unfortunately, have only one. The conversation is fascinating, and their questions reveal the depth of their separation from our world.

On the evening of the second day, Hussein and his father tell us we should hike out tomorrow if the weather in clear, to avoid being snowed in. It is agreed that Hussein will guide us over the mountain pass to another village that is on the ‘main’ road where intermittent trucks pass through. We’ll set out early to catch a ride, as it’s a two-hour hike, and Hussein needs to get back home long before dusk, because of the wolves. “Oh yes,” he says. “Wolves. Sometimes we lose sheep. An old man was killed last year near Koikanak.” ≈©

Publisher and purchase information for Afghanistan Before the Rain of Fire available here.

CHRIS LOWRY is a media producer and educator In 1988 he co-founded Street Kids International, producing videos promoting safer and better lives for street youth around the world. From 1998 to 2004 he worked in the field of child rights and health, consulting for the Canadian government with UN agencies, and served as a program director at Médecins sans Frontières-Canada. In the late 1980s Chris played a major role in founding The Journal of Wild Culture. He lives in Toronto where he regularly performs concerts as a singer. View Chris’ site — ecotone.ca

Comments

A riveting travel tale and,

A riveting travel tale and, given the last 40 years of Afghan

history, deeply poignant. I am filled with regret that I somehow

neglected to pursure such unpredictable travels.

I too was in Afghanistan in…

I too was in Afghanistan in 1977, though being Australian, travelling in the other direction, east to west. I spent a few days in Bandi e Mir with two travelling companions I met on the way, an American woman and a Dutch guy , all of us under 30 years old. After we left there and returned to Kabul, we heard that a British girl was killed down by the lake, shot by a tribesman.

It was a wild place though the people I met were wonderful with a sense of humour not found in other Islamic places I passed through.

I treasure my time in Afghanistan and will never forget a year later picking up a week old newspaper in a Greek taverna and reading that the Russians had invaded. I cried for what I could see was coming to the Afghan people and now it has been going on for over 40 years. I fear for what is happening there now with the Taliban takeover, especially for women and girls, but I hope what has come now is at least peace.

Thanks for this note Judy,…

Thanks for this note, Judy. How extraordinary to hear that you were there right around the same time, in that calm before the storm. I share your sadness and concern for what is happening now in Afghanistan; it is a bitter and brutal turn in their long ordeal. Here is a useful piece by Tariq Ali — http://www.defenddemocracy.press/debacle-in-afghanistan/

Add new comment