The Hindu deity, Shiva, one of the supreme beings who creates, protects and transforms the universe. was the destroyer of the three cities of the demons. [o]

It is the beginning of the twenty-first century and most humans remain inhabitants of what James C. Scott calls the ‘Multispecies Resettlement Camp’ – the aggregation of men, women, children and their domesticated plants and animals that was made possible by the development of agriculture. His book, Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States (2017), takes a jaundiced look at sedentism – the staying put that initially gave rise to urban culture and that would, some millennia later, come to define modernity.

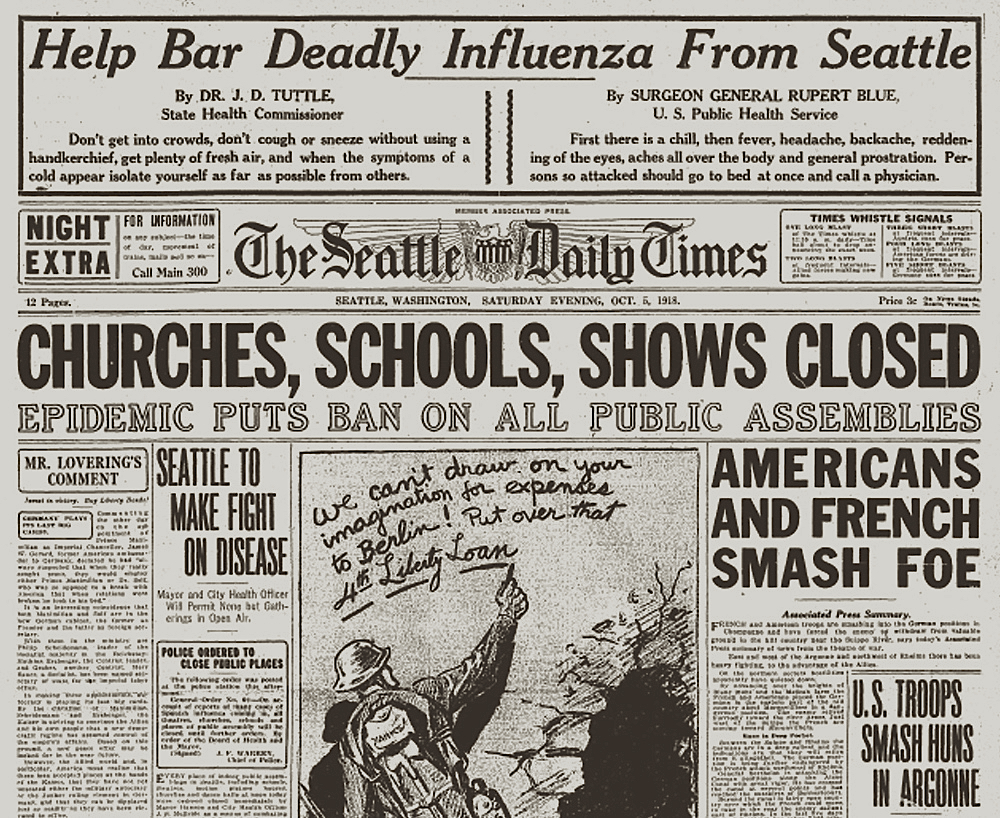

This progression represents our understanding of the development of Western civilization, which we are accustomed to celebrate – or did, until a couple of months ago when we reaped its corollary of epidemiological terrorism. As city dwellers, and more broadly, as subjects of highly interdependent, globally connected states, we remain prey to the “chronic and acute infectious diseases that devastate the population again and again,” which Scott identifies as a primary characteristic of the very earliest states.

Early states were reborn after repeated pandemics, yet survival required a fundamental reevaluation of accustomed ways of life.

Scott’s ambit spans across the early states that emerged in Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley, and Egypt in around 2500 BCE, and a little later in the drainage basins of the Yellow and Yangzi Rivers in China. But he extends his review of ‘civilized’ humanity to a moment, at the beginning of the seventeenth century, when urbanity at last predominated over its antithesis, the world of non-state peoples. These barbarians, from the very beginnings of emergent states, and entirely beforehand, had always been vastly more populous.

We Americans are heirs to one of the last great ‘victories’ of the civilized world over the barbarian. That victory was won, initially, by our introduction of the myriad zoonoses – those diseases we share with our domestic animals – to which our habitual sedentism in the ‘Multi-Species Resettlement Camp’ have made us hosts. Scott writes, “Once a disease becomes endemic in a sedentary population, it is far less lethal, often circulating largely in a subclinical form for most carriers. At this point, unexposed populations having little or no immunity against this pathogen are likely to be uniquely vulnerable when they come into contact with a population in which it is endemic.”

He notes that Native Americans had been “isolated for more than ten millennia from Old World pathogens” and succumbed in horrifying numbers to the diseases that the earliest colonists brought with them. It should be remembered, however, that Europeans were not themselves immune to novel infectious disease, having lost perhaps one-third to one-half of their population during medieval pandemics. Despite their partial epidemiological eradication, the more complete destruction of Native American populations required, as Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz notes in An Indigenous People’s History of the United States (2014), “three hundred years of colonial warfare, followed by continued wars waged by the independent republics of the hemisphere.”

A two minute silence in London and elsewhere took place on November 11, 1918 — as well as days of great boisterousness. Within a week a noticeable spike in influenza cases followed. [o]

So, just as early states were reborn after repeated pandemics — medieval Europe survived debilitating plagues and Native Americans survived a concerted pathogenic assault beginning in the sixteenth century — the world will survive COVID-19. But in every case, the argument can be made that survival required a fundamental reevaluation of accustomed ways of life. Early states collapsed under the pressure of disease, but their surviving populations melted back into the world of un-taxed, non-state peoples whose support strategies included slash and burn cultivation, small scale horticulture, maritime foraging and hunting and gathering. After devastating early losses, Native Americans adopted both the firearms and the domestic animals of their oppressors. Now, after a limited die-off of vulnerable populations, survivors of the COVID-19 pandemic will likely fundamentally challenge the political calculus of the modern state.

But what is certain is that, for the foreseeable future, the preponderance of the global population will remain tax-paying creatures indebted to their particular continental state, entirely trapped for their livelihood within a global web of capitalist trade. We, as a species, have been domesticated as surely as we have functioned as the agents of plant and animal domestication. As Michael Pollan and others have remarked, we have become slaves to landscapes designed to provide us with a consistently abundant food supply. That dependence has been extended, at least since the mid-nineteenth century, to include a reliance on the state — together with the corporations it embraces for our travel, entertainment, news and personal communication. We are faced, in the longue durée, not only with the collapse of states, or of empires, but with potential global, systemic disintegration. Perhaps it is unlikely that the-little-virus-that-could, COVID-19, will be the agent of that cataclysm, however it certainly constitutes one element in the decay of urban centers that Scott establishes as a characteristic of the ancient world.

Scott also argues that the repeated collapse of early states was due to the rise of infectious diseases caused by a number of things: crowding and the domestication of animals; the ecological disaster caused by deforestation and the salinization of over-irrigated croplands; and the practice of total war in which the population of the losing state was captured as slaves and their urban infrastructure razed. It does not require a great deal of imagination to understand that the fragility of our current global civilization – a manifestation of hyper-sedentism compounded in its pathologies by the hyper-mobility of our work, trade and leisure – is similarly threatened, and that these threats are inextricably braided in a world of metastasizing diseases, climate catastrophe, and habitat destruction together with extinction-grade military lethality.

The story of the great influenza pandemic of 1918 was not just one of death and tragedy, but also one of community and service. [o]

In 1918-1920, the Spanish flu impacted 25% of the global population of 1.8 billion and killed between 17 and 50 million people in three distinct waves of infection. Less than half a century later, from 1957-1958, Asian flu killed a million people world-wide, including 116,000 Americans. In 1968, the Hong Kong flu killed over a million victims. HIV/AIDS was first identified in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 1981 and has since killed 36 million people and remains a virulent threat in sub-Saharan Africa where over 5% of the population is infected.

In a highly urbanized world, chronic and acute infectious diseases strike crowded populations again and again. Little has changed since humans elected to forgo survival strategies in a variety of ecological habitats for the concentrated production of grain and livestock in early states. Now we rely on agribusiness and factory farms to funnel food to endlessly conjoined urban, suburban and exurban developments. We wait helplessly for the latest vaccine while new strains of disease quietly gestate in fetid congeries of human habitation.

We live in a world characterized by its epidemiological, ecological and political fragility.

For Americans, a secondary impact of this latest epidemiological threat is the backgrounding of our concerns for global warming, for the apparent selection of a deeply flawed Democratic Party candidate for the Presidency in 2020, for the endless wars in support of Empire, and for all those other pressing issues that evaporate in the presence of impending death. The unfolding threat has already caused the cancellation of the American people’s other opiate of choice, national sporting events, it has disrupted travel and will likely result in a broad economic recession. As we contemplate these trivial impacts, truly existential terror awaits.

We live in a world that is characterized by its epidemiological, ecological and political fragility. Its continued existence, our continued existence, is constantly at threat. Crises such as 9/11, Katrina, continent-spanning wildfires — and now COVID-19 — that have so recently piled up across the globe, are not black swan events, appearing out of nowhere: they are manifestations of this inherent fragility.

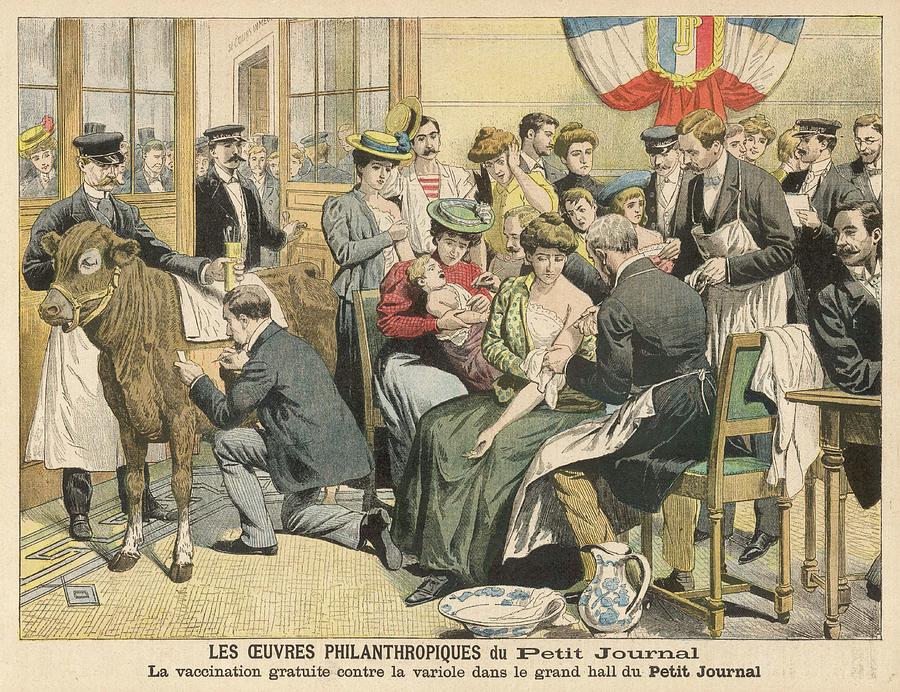

Free smallpox vaccinations in France. No effective vaccines were available to treat the Spanish flu strain of 1918-19. Citizens were ordered to wear masks and schools, theaters and businesses were shuttered before the pandemic came to an end. [o]

While statism and its symptomatic urbanity has spread across the planet, barbarians are in full retreat, marginalized in the least propitious areas of the world. Their shrinking territorial base no longer represents a safe haven for those fleeing a failing civilization. Change must come from within, and it will be forced upon us through crisis.

And so we are left to question . . . ‘Can COVID-19 be the one that, like Shiva, is the destroyer who ends this cycle of time and begins a new Creation?’ ≈ç

READ part two of this three-part series.

JOHN DAVIS is a California-based architect who also writes a blog, Urban Wildland, and has contributed many articles to The Journal of Wild Culture. He lives in the Upper Ojai.

Add new comment