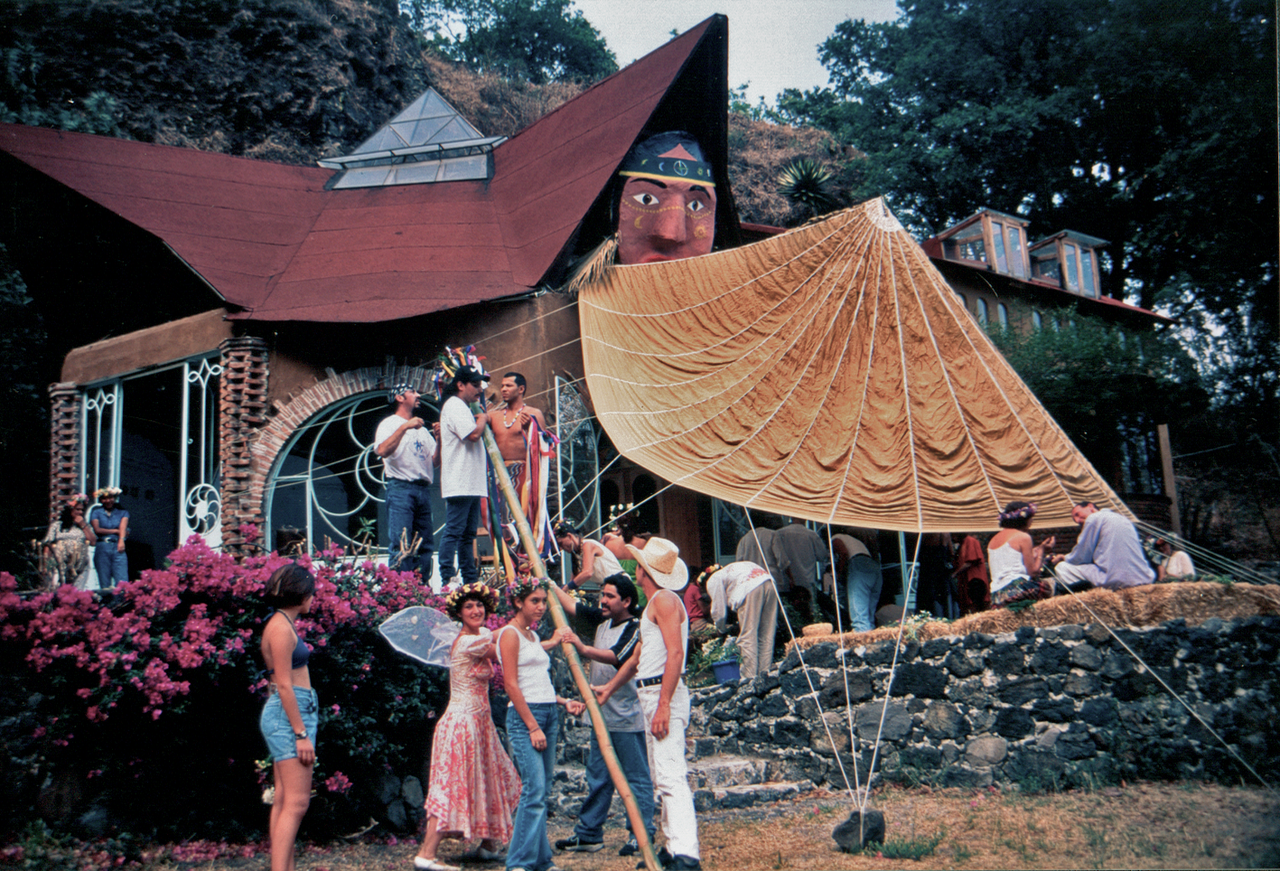

Before Huehuecoyotl, the Illuminated Elephants caravan tore up the Americas. [Photo by Jan Svante Vanbart].

TEPOZTLÁN, MEXICO — On a balmy Sunday evening in winter, February 26th, 2017, six friends are sitting around the kitchen table in a house just outside the town of Tepoztlán, in Central Mexico, to plan a massive celebration. Shots of mescal are lined up and emptied and when there is no more mescal the tequila is brought out. A plate of limes picked off the trees outside the door is passed around to quell the sharp taste.

But it's not just the liquor that has bite here. This group of friends have lived together, on and off, for decades — three-and-a-half, to be exact. So, being mature but not quite elderly, and very savvy about each other’s ornery ways, they know that at any moment a heated debate might be right around the corner.

Tonight things have started out calmly. Quesadillas warm off the stove and bowls of green salsa keep company with the drinks, and the conversation is peppered with dry, affectionate teasing. For an hour or so irony and laughter rule. Then, as expected, the talk swerves precipitously into communal operations. In this case it’s the upcoming 35th anniversary celebration, in the planning stages for weeks and now six days away.

The faces around the table are directed at Alberto who, as usual, is at the centre of organizing most things in the community.

“So is it a fiesta or is it a festival?” asks Kathleen.

“It’s definitely a fiesta,” says Alberto.

“How many people are we expecting?” says Giovanni.

Her comment — and her concern that the group at least acknowledge the hazards of impassioned idealism — hangs in the air.

Alberto frowns and stares out into space, silently calculating the fruits of their networking. “Six hundred. Maybe more.”

“That is not a fiesta!”

“We agreed before. Remember? It's not a festival.”

“And it won’t be,” says Alberto, nonplussed. While he explains why his numbers won’t be a problem, Liora and Kathleen lock eyes. Beneath the surface of the wobbly start to the discussion is an abiding love and respect by and for each person around the table. Yet that doesn’t mean things are, or ever have been, easy in Huehuecoyotl.

Alberto, the charismatic Mexican-born leader/non-leader — son of a man famous for discovering the royal tomb inside the temple of inscriptions in Palenque, among other things — is being questioned about logistics: Will alcohol be allowed? What if people bring their dogs? What about smokers and tossed butts and roaches during the most fire-prone season of the year? What if people go walking on the mountain in the middle of the night? What’s expected of volunteers and what are they expecting of us? Can we feed everyone? The list goes on.

Liora Adler performing with the Illuminated Elephants to a rapt audience. [Photo by Jan Svante Vanbart]

An early promo shot of an unclassifiable troupe. Giovanni Ciarlo (far left), Alberto Ruz (centro), Andres King Cobos (top), Kathleen Sartor (far right, middle). [Photo by Jan Svante Vanbart]

Alberto’s tranquil manner belies either a natural style or pure strategy. Though he's as experienced as anyone here in these types of events, those around the table also know what it’s like to work and live with him — what shines bright and what sucks light: just as he is with them. With most compellingly attractive and visionary leaders, the path of glory can also bring a lot of surprises, not all good.

Kathleen asks questions about feeding 600 people. She lists what might go wrong in the kitchen.

“It will be fine,” says Alberto, as if waving away a wasp. “It will be great.”

The faces around the table show, if not doubt, a lack of commitment. As if they’re saying, “Sure, we can imagine a rosy outcome. But let’s first give the dirty details a going-over.”

“It will be fine?” asks Kathleen. “Let’s hope so.”

The gathering breaks up on a friendly note. As they bid goodbye, Kathleen's last comment — and her concern that the group at least acknowledge the hazards of impassioned idealism — hangs in the air.

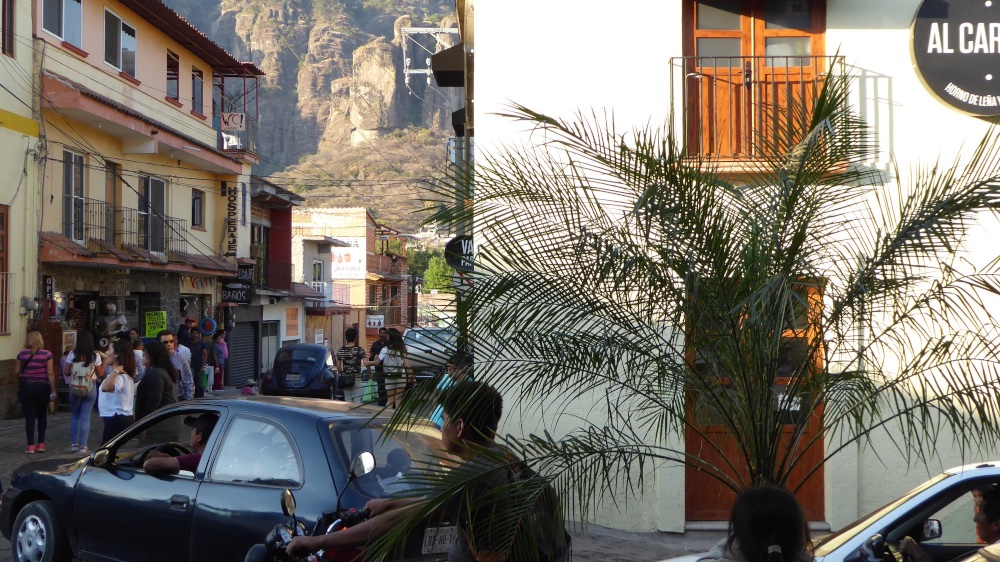

Land and Opportunity

The 5-acre plot of land on which the ecovillage of Huehuecoyotl (meaning “very old coyote”) is built was purchased in 1982 for $50,000. “Today,” says Alberto, “you might be able to buy a tiny piece of it for that.” Huehue, as it is called by locals, is near the town Tepoztlán (population 15,000), about a 90 minute drive south from Mexico City. Located in a valley surrounded by a uniquely majestic, jagged mountain chain called a sierra, said to be similar only to one other in China, Tepoztlán is designated a pueblo mágico (magic town) by the Mexican government — not just for the beauty of its surroundings but also for its proximity to the ancient and sacred El Tepozteco temple and pyramid at the top of a mountain, within view of the town. As a result — and because annual temperatures are between 60-80˚F/16-27˚C — the region is a popular tourist destination, and for residents of Mexico City a favourite weekend retreat. For all these reasons an ex-pat seeking a cheap lifestyle in Mexico should look elsewhere. Though there are lots of beautiful places in this astonishing country, there is only one Tepoztlán.

Huehue is a 20-minute drive up the mountain from Tepoztlán on land tucked alongside the bottom of a steep, spectacular mountain rock face. The community has reached its limit of fourteen houses of various sizes, built in close proximity; the two furthest ones are a two minute walk from each other. In some ways, living here is not unlike growing up on a suburban block where a resident knew, and maybe was friends with, most of the thirty or forty neighbours who shared the same residential space; and, with luck, its micro-regional identity.

What’s different about Huehue is that there is an expectation to participate in the community: an expectation to contribute to communal expenses, have a designated role, and be an active contributor to community events — like the 35th Anniversary ‘fiesta’. As with all situations where people are required to work together, some do more than others, and some are more capable or easier to get along with. Given that all human beings are not all made the same and not mutually obliging, wouldn’t it be wiser for people to live in their own homes, only have restricted occurrences in which they have to interact with each other, where people live in fenced-off tracts of land in subdivisions where no one has to depend on anyone else? Simple enough: Pay your taxes, keep your nose clean, don't get into trouble with the Sovereign. The 17th century philosopher Thomas Hobbes thought the natural state of mankind was as a "warre of every man against every man". Far fetched perhaps, but for some this is the ideal and desirable state — the preferred norm.

A man carries a palm trees through the streets of Tepoztlán. Photo by Whitney Smith.

Watching the Rain Come

A couple of days after the drinks party Kathleen Sartor’s mood has changed; she's pensive and more serious than usual. Sure, she was working hard on the preparation for the fiesta — pruning unruly bushes, cleaning up the community grounds, making lists with a team of women who were taking charge of the kitchen, doing whatever else she noticed needed to be done to host the outside world, which was, in her case, a lot. But something else is preoccupying her. Perhaps it’s that, like any astute event organizer, she's carrying the anticipation of what might go wrong and prevent the fiesta from being a smashing success.

“Yes, it’s that, partly. But we’re also having some problems with our house.”

The problem is the drainage on the upper slope of their property. In the wet monsoon season, from June to October, the rain pours down from the mountain and turns Huehue into a spectacularly beautiful green landscape that, if there is no natural course or constructed channel to direct the water further down the mountain, the water seeks places to pool and flood. To not manage water flow carefully is to invite a flood in your kitchen or bedroom — or worse, your neighbour’s — what everyone strives to avoid. The terms striving to avoid and avoiding are not transferable when it comes to ‘the call of nature’ in the sierra of Central Mexico, therefore each homeowner depends a lot of what her neighbours do.

“It’s one of our bioregional problems. If you haven’t dealt with your water issues by June, tough luck.”

To explain, Kathleen takes me to see her house and the rock wall that needs to be rebuilt. On the way there, across Huehue’s common green space that doubles as a soccer field, with goal standards on either end, she runs into Laulin Osher (pronounced Lau-leen), the daughter of one of the founders of Huehue. Laulin, 30, is a school teacher and a member of the fiesta planning committee. Though the fiesta itself will have a healthy attendance of her peers, Laulin is the committee’s only member in her age group. As she and Kathleen talk about what needs to be done for the fiesta, now three days away, Laulin demonstrates a full grasp of several aspects of the event: the roster of performers and those participating in ceremonies, the sound and lighting, and much else. She’s clearly a bright and accomplished young woman who’s taken on a lot of responsibility, and her confidence somewhat mirrors how Alberto sees things: "Of course there's a lot to do and a lot to think about, but it’ll be great . . . sure it will!"

As Laulin departs Kathleen gives a little rah-rah fist strike in the air — as if Laulin's energy and attitude will carry the day.

Kathleen and Giovanni’s house is two-storeys and painted rust-orange (a colour common in Huehue houses) with a small workshop built a few metres away; beyond the workshop is a dry latrine (about 75% of the 14 houses in the community have flush toilets). Abundant, dry foliage surrounds the patio and the house: palms, cactuses and an enormous agave plant with a thin rod the thickness of a man’s arm sticking four metres in the air; from the plant’s centre sprouts numerous hard, spear-like leaves. If Agatha Christie were here she might imagine a shadowy night where someone is accidentally impaled on one of these. No wonder tequila packs a punch.

Around the back of her house Kathleen inspects the upturned wall of rocks. It doesn’t help that one of her neighbours, who is out of the country for several months, “isn’t exactly cooperating”, and that the neighbours above her got rid of the concrete drainage canal when they put in their new gardens.

These are acts Kathleen regards without acrimony. “It’s not that they’re bad people and not friends. Like me, they have their own set of things to deal with. We’re people living our lives.”

But isn’t an ecovillage the kind of place where such interconnections get worked out from the beginning; or at least get resolved through some process of consensus, or some other facilitation technique where groups of people looking for a solution are brought to a common agreement?

Like a teacher with a curious but thick student, she measures her words.

Huehuecoyotl from the top of the mountain. [Photo by Jan Svante Vanbart]

“If only it were so . . .”

Kathleen crouches by the rock pile, staring into it as if she can see into earth space. “I need to find Giovanni.”

When she gets to the theatre where he’s been working on a giant papier-maché coyote mask, now laying forlornly half-finished on a table, without its maker, she leaves and stands outside surveying the soccer field. The sound of singing and guitar playing comes from Andreas’ house, about thirty metres away.

Half Sun Dancer, Half a Dozen Things

Andres King Cobos is one of the original members of The Illuminated Elephants, the group of activists, environmentalists and artists that included Alberto, Kathleen, Giovanni, Liora and others who traveled in the Europe, India the US and Mexico before they created Huehue. Its founders discovered this land only after spending years as nomads, first without, then with converted vans and school buses. It is Andres, as much as anyone in this community, who diligently practices intuitive communication with the forces that beckoned them here. For two decades he has been Danzante del Sol [Sun Dancer] of the first Circle of Dance in Mexico, founded by the Mesoamerican Tlacaelel Tradition Grandfathers and Don Faustino Yautecatzin in 1980. Like Alberto, his track record as an irrepressible co-founder shows a passionate dedication to institutionalizing artistic and spiritual visions: Grupo Juan F. Noyola, UNAM (1965-68), Cine Club de Economía (1966-68), Gambusinos (1969), Situationist International (1968-73), Hathi Babas Transit Ashram Company, illimited (1973-77), and then The Illuminated Elephants.

Preparing for an event in front of the Huehue theatre, the large common space that includes a kitchen, dining room and library. [Photo by Jan Svante Vanbart]

It could be said that if Alberto is the titular (non-)head and (non-)leader of the community, then Andreas is its poet, philosopher and student shaman. Of course all members of the community are contributing to its philosophical and sacred expression and evolution, but Andres is focused daily on these matters. And, being married to a Danish woman and formerly married to another Dane who is also his neighbour a stone’s throw away in Huehue, he has spent much time in Europe and has drawn from its intellectual and artistic nourishment, the café life of Paris and Copenhagen and the networks that spring from those places.

When Kathleen arrives at the door of Andres’ house, he and Giovanni are in the middle of writing a song for the fiesta. Holding a pad of paper with a page full of tiny, neatly written lyrics, Andreas sits at the feet of the taller Giovanni who holds the guitar in an odd mid-air style, never resting it on his knee. Kathleen backs out of the door without disturbing them.

“Life is good,” she seems to be saying, “and . . . there is so much to be done.”

The rocks can wait.

Deliberately Moving Away Together

The idea of intentional communities is not something new dreamed up by hippies in the 1960s. For all of time there have been small groups who sought to get away from the larger population, for reasons of idealism, oppression or sheer exasperation, to establish an enclave where they can live the way they want to — away from the norm — as opposed to the way others think they should or must.

In his foreword to Finding Community by Diane Leafe Christian, Richard Heinberg writes, “We humans evolved in small hunter-gatherer bands, thus roughly 99 per cent of our history as a species has been spent in groups of 15 to 50 individuals where each knew all the others, and where resources were shared in a ‘gift economy’. Even in recent centuries, the vast majority of people lived in villages or small towns. Little in our evolutionary past has prepared us for anonymous life in mass urban centres, suburbs and exurbs. Therefore the goal of living in an intentional community with friends of like mind carries a deep and perennial psychic resonance.”

In the recently published 7th edition of The International Communities Directory there are 1200 communities categorized by geographic locations or type. (One can only imagine the hundreds or thousands that prefer to fly under the radar and not be listed). The Directory’s list of types of intentional communities includes: Commune (organized around sharing almost everything), Ecovillage (organized around ecology and sustainability), Cohousing (individual homes within group owned property), Shared Housing, Cohouseholding, or Coliving (multiple individuals sharing a dwelling), Student Housing or Student Co-Op, Spiritual or Religious Community, Unspecified, or Other, Transition Town or Eco-Neighborhood (focused on energy/resource resiliency), Traditional or Indigenous Community.

An ecovillage could theoretically be any formation of people living together where the shared aims focus on matters of ecology (the relationship of species to habitat) and sustainability (conserving an ecological balance by avoiding depletion of natural resources). According to an influential article, “The Eco-Village Challenge”, written in 1991 by Robert Gilman, the concept comprises “human-scale, healthy and sustainable development, full-featured settlement, and the harmless integration of human activities into the natural world.” Gilman favored limiting the population to 150 inhabitants, the maximum size by which a working social network could function effectively — according to the teachings of sociology and anthropology.

But the aims of ecology and sustainability are also not new to communities. If community members are trying to save money and make the most of what they have, they'll carefully regard the local ecology and issues of sustainability, whether they know it or not. What intentional community would start up today that did not consider these factors? If we look at the Greek root of the word economy — “the rules of the household” — to do so just wouldn’t make good economic sense.

Being at their farm . . . it made me the way I am today.

When Kathleen takes me to see the Huehue community garden she talks about how — though growing up on the outskirts of Minneapolis — she spent many weekends and most summers at her German-French grandparents’ farm an hour away.

“I was busy there,” she says as she digs her hands into the dry soil and pulls up over-grown celery and New Zealand spinach. “Shelling peas, pulling fruit worms off the fruit trees, baking bread, canning tomatoes and peaches and green beans. I was my grandfather’s favourite, but only because I was there more than my brother and cousins.”

She pulls her hands out of the soil. She has long, flowing silver-grey hair that falls half way down her back; when she stands up she flips it off her face. It’s a style she’s had since leaving home as a teenager when her Norwegian mother insisted her hair be anything but long and straight. Perms were the thing.

“Being at their farm . . . it made me the way I am today. I learned about water systems, how to use the grey water, how to use a latrine. They didn't have plumbing until 1962. Everything they ate was something they’d grown. They raised their meat, were part of the dairy co-op where they got cheese and ice cream. And though they were devout Catholics, very religious, I learned about nature and spirituality from them.”

As always in Huehue, yellow and orange and black butterflies come and go, riding the warm breeze that flows up from the valley.

A sequence of ceremonies during the fiesta ended with a tribute to the founders (left) and their children. [Photo by Whitney Smith.]

“They had such a high regard for everything on the farm, and how everything was used. Martin Luther King was hardly a Catholic, but my grandparents lived by something he said, that we accept suffering for the good of the cause to reach the goal.”

Though the hundreds of ecovillages around the world are unique to the location, climate, local culture and the personalities of the individuals and the general group psyche, in his book Ecovillages: New Frontiers for Sustainability, author Jonathan Dawson writes that what distinguishes ecovillages from other urban or rural eco-regeneration projects is: “Community is of central importance; shared values and the sharing of resources and facilities are the norm; ecovillagers seek to win back some measure of control over their resources (food, energy, livelihoods, houses); they are built by groups of people, rather than traditional developers or other official bodies; and, they are more or less entirely reliant on the resources, imagination and vision of the community members themselves.”

In Huehue, imagination is a resource that fuels much of its communal activity, and is an important social glue that keeps the community evolving. No wonder Huehue's motto is “art for ecology and ecology for art."

A Little House for Music

On Thursday night, two days before the fiesta, Giovanni takes me out of Huehue to a house up the paved road and then down a rocky, gnarly one where we will play music.

“A music party?”

“Not really a party,” he says. "But we'll play."

When we get there it is a small building with three rooms, designed by its owner, an Argentine drummer and drum maker named Mo. His music space (he lives close by) is made especially for playing music in a way that holds jamming in high regard. For instance, in the back is a tiny room, big enough for a tiny desk and chair with about fifty of Mo's drums — his own and ones for sale, all made by him — that are resting on shelves and wrapped in beautiful cloth bags. This is where the smoking is done. In an even smaller room, at the entrance, is where we drink and eat. In the main room, filled with about a dozen types of drums and percussion instruments, only instruments are allowed. In the soft decor of fabrics hung on the walls and stools and cushions on the floor, we settle in for a night of playing. The music is free; it rises and falls, stays still and flies like a hooked beak bird to great heights, evolving without plan or verbal negotiation. The players trade instruments — this guitar, that bass, this mandolin, this conga — and when someone wants refreshment they get up and go to either small room. There the intensity and focus of playing is relieved; conversation and laughter take over, then when we're ready, we go back to play again. Mo has created a physical space and attitude to art in which the process of making music is deeply respected.

Night at the fiesta in the food camp. [Photo by Whitney Smith.]

Giovanni’s guitar playing and singing rise to the top in this situation. Though he is very much not, according to an over-used and inaccurate generalization, a "typical macho Latin man", born in Italy and raised in Venezuela, his music is imbued with a masculine presence from these countries of the best kind. Surprisingly, for someone who has played for decades and performed professionally in hundreds of different settings where he takes a firm lead of his band and the audience, Gio is untrained in music. What he has is a command of his unfancy guitar and full, rich voice — with full access to what joy and passion pour through him. His funny, smart and lighthearted personality, large as life in social situations, comes out generously through sound in these sessions. Complex his music is not, but what it is is rich and satisfying for fellow musicians and listeners. It appears that Giovanni is at home everywhere; and having lived on the road with the pre-Huehue caravan for several years (where he and Kathleen slept in their tent on the top of the bus), it’s clear that he’ll do what is necessary to entertain in any situation.

A Tribe That's Always Been

Finally fiesta day is here. A generator truck pulls in and various electrical devices are hooked up to it through cables winding through the grass. Alberto’s large white and blue striped tent (40’x40’) is erected in the middle of the soccer field; the tent is one of two main performance areas for entertainers and ceremonies; audio and lighting equipment are being set up under the tent and tested.The second performance space is more sacred: in front of the amate tree, the very one that inspired Huehue’s founders. The tree — enormous, multi-branched and growing out of a rock face like a resplendent, grey octopus — is an important role in the Huehuecoytl genesis story. In one of several chronicles of the Huehue storhy, Alberto writes of their search for a place to settle in Mexico. "We travelled for more than six months, from the sierras and forests of Michoacan to the coasts of the Caribe maya, following all the tips, signs and suggestions. In 1982 someone told us about a place near the recently built road to Santo Domingo Ocotitlán, near the "magic town and sacred valley of Tepoztlan.” There was no path to reach the place so we climbed a lava rocky hill and came out onto three cultivated corn terraces, at the feet of the mountains. Some 150 yards in we saw a gigantic tree. As we approached it we knew, felt, that we were finally coming to the end of our quest and pilgrimage.” If an ecovillage’s purpose is to live with respect and sensitivity to the land it inhabits, then this tree was a regal reminder — un arbol magicó.

People stream in, and then and more of them. A table is set up at the gate and after people pay 100 pesos/$5 US (unless they are locals from the nearby villages and towns, who get in free) and then at a second gate they are smudged with sweet grass and other mixtures and follow a path sprinkled with red and yellow rose petals. A relaxed yet energetic mood runs through the crowd as organizers, volunteers and technicians prepare the scene.

Of course food in Mexico delivers magic, and so a meal of mole and cactus leaves, mushrooms and black beans, available to all guests, brings people together and lays a foundation of generosity and warmth. Later in the afternoon at little portable kitchen stations local grandmothers, mothers and daughters sell a variety of dishes: buttered corn on the cob on a stick; scraped corn on the cob in a dish with mayonnaise, lemon and chilies; tamales; pozole (a soup made of large, skinned kernels of corn, also known as hominy, vegetarian or with chicken and garnished with sliced radishes, chopped onions and dried oregano); chicken in a tamarind sauce; cecina (a thinly sliced beef in tortillas with salsa, Mexico’s ubiquitous condiment); the quick standby, quesadillas are tortillas with melted Oaxacan cheese, not unlike a roped mozzarella. Every dish is delicious, hot and ample.

The handful of tables where artisans are selling crafts and books are doing a brisk trade.

Mother, grandmother and daughter doing one of the things they do best for the guests of the Huehue 35th anniversario. [Photo by Whitney Smith.]

But it is the presence of respectful and delighted people being in the presence of others that is giving this event its lift, and from there one cannot imagine how the event could go awry.

Ceremonies are held with acoustic music and singing, and then as the sun goes behind the mountain and evening comes, the stage lights take over. One by the one the musicians and singers take one of the two stages whose sound levels are well separated enough from each other that the artists can comfortably do their work, raising the level of heartfelt artistic expression, song by song. Indigenous and contemporary styles in the program sift into each other and back again. People of all ages are engaged by what they hear; there are some children, there are many in their twenties and thirties, many in their 70s, and many in between. A dozen young footballers find a place to play that fits with what everyone else is doing. The rule of making the guest list of the party as diverse as possible has happened naturally; the cosmopolitan and cross-cultural social nature of Huehuecoyotl has attracted its own, and, in the end, however many people came — about 400-500 throughout the day — they never strained the seams of the space.

The final performance before the dancing bands and DJs take over is Tribu, an ensemble famous in this country (they perform a popular weekly concert at the Museum of Archaeology in Mexico City), heard by a crowd of two or three hundred. A four-man group led by two who are original members since the 1970s, Tribu uses only instruments and vocalizations of the type used by indigenous tribes before the Spanish conquest that began in 1519. Dressed in leg and foot shakers (key instruments for most of the 90 minute concert) and playing whistles, flutes, drums of all sizes, pottery and stone objects that are struck with wood or other hard materials for percussion, this performance was the kind that makes you say you’ve never heard anything like it, anything as good or authentic or thrilling or moving — a performance of the quality that will not be forgotten, maybe ever, and makes you feel how lucky you are that you were there.

Into the night unfolds an elongated music set, not a rave but something equally transfixing. The music is strong, relentless, tasteful and loud. Convened by the fresh generation of the community, it went past the agreed upon shut-down time of 3 am, an irritation to those wanting to have the party over. No big deal. At 4 the sound man complied by turning the music down, but at 6:15 the volume creeped up again, stirring many out of their sleep. One of them was Kathleen, who rose from her bed and went over, saying, not obsequiously, “Suficiente!”

Two members of the four member ensemble, Tribu, in performance at Huehuecoyotl, March 4, 2017. [Photo by Elivier Sepulveda.]

After a couple of days of relative peace around Huehue, and full nights of sleep, the organizers returned for a post-mortem meeting. Its form verged between scrambled and intensely productive, but everyone got to share what they thought was good and what could have been improved upon. Three pages of comments were generated and one of the more important points raised was that two people who went walking on the mountain too late in the day got lost and had to stay up there, shivering until morning; the particular mountain that overlooks Huehue is so treacherously steep that one false step would be fatal, so at least they made the right decision. Next time more precautions would be taken.

At the end of the meeting the issue of the loud music at night was brought up. Laulin, the only one of late-night revellers on the committee, held her ground. “It was one night of the year.” There were different responses to this but it was quickly resolved; Laulin did a great job and was indispensible to the event. All in all, the meeting was an opportunity to praise the event and express thanks for each other’s participation — that and the serendipity of the divine somethings, the amate tree and the Mother Earth and Sky Father kith and kin, all of that, however expressed, pick your form, or not. The fact that it turned out so well, according to Alberto’s nonchalant, visionary non-authoritarian authority, was noted. A clear shimmering mirror reflected 35 years life lived well by old, old coyotes — however contrarily.

As the subject of the charismatic leader has been raised again, replete with peccadilloes that attest to his openness to full humanness and full maleness, here is a brief testament to Alberto, the community member who is judiciously appreciated and tolerated with equal love. This is from a letter written by Huehue member Bea Briggs for an application nominating Alberto for the Kozeny Communitarian Award, which he won:

“Alberto Ruz seems as comfortable driving a bus, blowing the conch shell, beating the drum and taking organic waste to the compost as he is speaking on an academic panel, sitting among indigenous elders or hosting government officials. As he approaches his 70th birthday, Alberto is as active as ever . . . advising the Legislative Assembly of México City, promoting the recently adopted Law of Rights of Nature . . . representing the Council of Sustainable Settlements of the Americas at the Global Summit of Ecovillages in Senegal . . . the list goes on. Because he is so charismatic and comfortable in the spotlight, it is easy to forget that, except for his writing, all of Alberto’s accomplishments were achieved in the context of a group. Although he calls himself Coyote Alberto, he is not a lone wolf. He is a dream weaver and mythmaker who has never given up on the vision of a cooperative society, never sold out the lure of a conventional life. With his trademark rainbow beret, wherever he goes he is authentically Alberto.”

John Quincy Adams once penned a definition that applies here: "If your actions inspire others to dream more, learn more, do more and become more, you are a leader.”

But don’t communities that found themselves on principles of decentralization and non-authoritarianism expunge the charismatic leader? Not really, says Bea, who works as a professional facilitator all over the world helping group members listen to each other and find effective solutions — together. “There are all sorts of different leadership styles, and they all have their merits.”

Andres, Alberto and Giovanni — bringing in the anniversay cake. [Photo by Whitney Smith.]

A day after the post-mortem meeting, Kathleen reported that she and Giovanni had hired some men from a local village who, being residents here, know about managing water in the rainy season.

An hour later, Andres, book in hand, dropped by and sat around the same table where the fiesta planning discussion had occurred earlier last week. People do stroll over to each other’s homes in Huehue, for no apparent reason but to say hello and share some time ; it’s a small community thing, a neighbour thing, but in this case Andres did have a purpose: he brought a poem to read.

“I want to introduce you to someone,” he said with a wry smile.

Why? A thousand reasons. And just because.

Hence, in that spirit — as is often fitting after fraught and rewarding galas crafted by fellow seekers, events that are allowed to fall quietly into memory — let us introduce you to a poet you may not have heard of, to close the proceedings and its report. Here is a man who has something to say, for all of us.

MY TRIBE

Earth is the same

sky another.

Sky is the same

earth another.

From lake to lake,

forest to forest:

which tribe is mine?

—I ask myself—

where’s my place?

Perhaps I belong to the tribe

of those who have none;

or to the black sheep tribe;

or to a tribe whose ancestors

come from the future:

a tribe on the horizon.

But if I have to belong to some tribe

—I tell myself—

make it a large tribe,

make it a strong tribe,

one in which nobody

is left out,

in which everybody,

for once and for all

has a god-given place.

I’m not talking about a human tribe.

I’m not talking about a planetary tribe.

I’m not even talking about a universal one.

I’m talking about a tribe you can’t talk about.

A tribe that’s always been

but whose existence

we can prove right now.

By Alberto Blanco, from his book Dawn of the Senses. Translated from the Spanish by James Nolan.

Petals scattered on the path from the smudging gate to the fiesta site. [Photo by Whitney Smith.]

For more photographs of the Huehuecoytl 35th Anniversary, go here.

This article was first published on March 12, 2017.

WHITNEY SMITH is the Publisher and Editor of The Journal of Wild Culture. He lives in Toronto.

ELIVIER SEPULVEDA's photographs can be seen at http://www.9mm.mx.

Comments

Thank you. Love to get to

Thank you. Love getting to know Huehue through your experience.

Just now finished reading

Just now finished reading this magnificent piece on Huehuecoyotl and their 35th anniversary celebration. Your sophisticated take on how personalities blend — and don't — to make up a viable long-term community was a great pleasure to read. The hopeful life is truly the one most worth living. Glad you mentioned that "communes" et al were not invented by hippies of the 60s, who were merely returning to a more rational model of community, beyond and beneath the radar of mass culture.

Yes, worth another look And

Yes, worth another look And your photos are fabulous. Great stuff.

Add new comment