The American Badger (Taxidea taxus) sometimes hunts in tandem with coyotes. [o]

Early in his tenure, according to the authors of Sinking in the Swamp, President Trump would reportedly badger former chief of staff Reince Priebus with, well, badger questions. Perhaps because Priebus’s home state of Wisconsin has dubbed the badger its state animal, Trump would interrupt his discussions on the minutiae of healthcare and foreign policy to ask more important questions: “Are they mean to people? How do they work? Do they have personalities or are they boring?" The president would also request that Priebus show him some badger pictures.

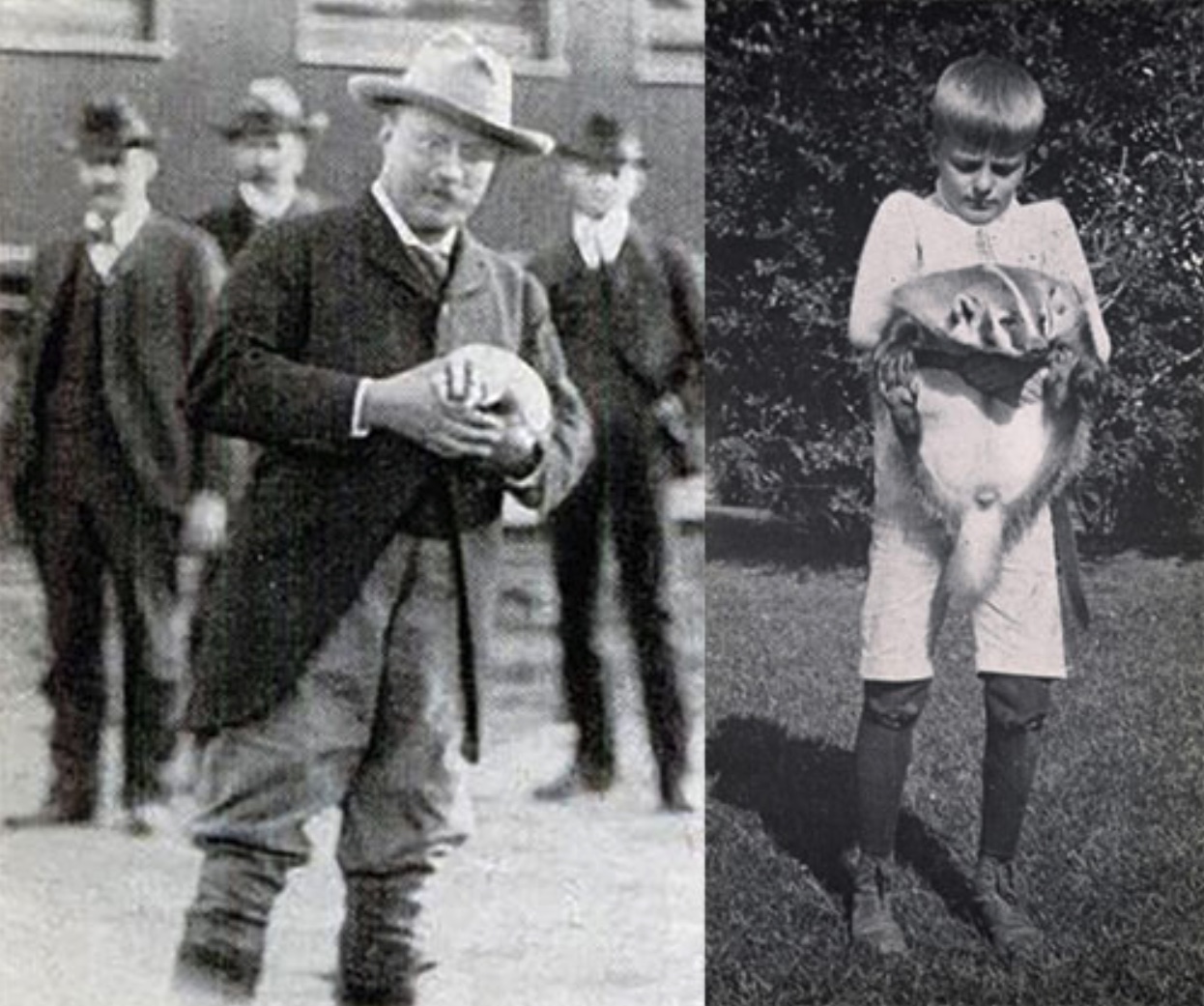

Trump is not the first president to take an interest in badgers. Teddy Roosevelt actually had a pet badger named Josiah who liked to nip at people’s ankles. Although much beloved by the Roosevelts, Josiah did not last long at the White House: in less than a year, the badger’s temper had soured, and he was relocated to the Bronx Zoo.

He awakened next to Badger, who admonished him for his foolishness and prescribed him a 'stiffening medicine' . . .

As it happens, humans have long been fascinated by badgers; they have occupied a special place in the human imagination, as author Daniel Heath Justice shows in his book, Badger. Our preoccupations with them perhaps say even more about us than about these ill-understood creatures.

Even in terms of their taxonomy, badgers have bedeviled scientists and the natural philosophers of yore. While the scientific consensus now is that badgers belong to the family of mustelids (along with otters, ferrets, minks, wolverines, and weasels), historically the badger has been associated with dogs, hogs, and even bears. Carl Linnaeus, regarded as the father of taxonomy, had assigned the Eurasian badger to the Ursus family; as Justice notes, badgers do share certain characteristics with bears, from their non-retractable claws and coarse fur to their winter torpor habit and omnivorous diet.

Petroglyph of Kokopelli. Sand Island area, Bears Ears National Monument, Utah. [o]

Badgers distinguish themselves from other mustelids by their digging proclivities. They dwell in holes they dig called setts, and these setts can vary in complexity and purpose. The solitary North American badger tends to dig temporary burrows, while the more social Eurasian badger sometimes constructs rather elaborate setts, complete with separate latrines, that can serve as more permanent homes for multiple generations of badgers.

Because badgers are mostly nocturnal creatures who live in the ground, they do not interact much with humans. Despite their reputation for aggressive behavior, badgers tend toward shyness, largely keeping to themselves if left alone — though they will not shrink from defending themselves when threatened.

In fact, the verb badger etymologically does not refer to badger behavior, but rather our own: through badger-baiting, we humans badger badgers to death, tormenting them with attack dogs and other cruelties. The dachshund, literally badger-dog in German, was bred specifically to dig out badgers from their setts and round them up for the purpose of badger-baiting. The dog’s “long body and short legs are perfectly suited for pursuing a badger into its tunnels,” according to Justice.

Digging some dirt . . . Badgers dig burrows to find food underground and make their homes by digging tunnels and caves, using grass and leaves for bedding. [o]

The human-badger relationship is a complicated one, to be sure. Perhaps because humans have limited interaction with badgers, the human imagination of badgers has run wild, imbuing these creatures with a mythical character and prowess in the stories we tell. As Justice recounts in his book, badgers have been imagined to possess an earthly knowledge of divination and healing, which they can use to resurrect the dead and to cure sexual dysfunction and impotence.

According to a Hopi story, “The Man-Crazed Woman”, a man was unable to satisfy his wife sexually and, after enduring much abuse from her, jumped off a cliff. He awakened next to Badger, who admonished him for his foolishness and prescribed him a “stiffening medicine” that would give him a permanent erection. The man, whose back had hunched due to his fall, would come to be known as Kokopelli, the revered fertility being.

In the corpus of the human imagination, badgers are also stalwart warriors, steadfast defenders of tradition, and loyal sidekicks (the badger is the Hufflepuff mascot). The most famous literary badger, according to Justice, is Mr Badger of the Wild Woods in Kenneth Graham’s classic, The Wind in the Willows. Justice describes Mr Badger as an archetypal badger who is “the voice of history, tradition and the power of the land itself.”

"He bites legs sometimes, but he never bites faces," said Roosevelt's son, Archie (right). Josiah was a gift from a 12 year-old girl in Kansas to Theodore while on a railroad tour of the west. [o]

For all the gravitas we may ascribe to badgers in our tales, however, we also treat living, breathing badgers as vermin to be managed if not exterminated. In the UK, panics over the spread of bovine tuberculosis in cattle have led to controversial, government-backed badger culls. Here, too, the human imagination is actively at work: as Angela Cassidy observes in Vermin, Victims and Disease, the public debate in the UK over badger culls has hinged not on the science of bovine tuberculosis but on the imagined “goodness” or “badness” of badgers, defined of course on humans’ terms.

For badgers, then, the human imagination can be a matter of life and death. For, in our hands, the human imagination is no mere storytelling device; it is a power we exert over the world and its inhabitants, and we exercise it in a manner that is sometimes ruthless, irrational, and capricious, much like ourselves. ō

DEAN ERICKSEN, a librarian who does not work in a library, majored in philosophy at Amherst College and received his MLS from Indiana University-Bloomington. He is fascinated by the juxtaposition of apparent opposites (human/animal, culture/wildlife) and what it says about us when and where these oppositions collapse under scrutiny. He lives in Dayton, Ohio,

Add new comment