The band's posters from the sixties.

LONDON — Fifty-two years ago a slender bridge reached across musical, racial and cultural divides. In 1966, a group called The Byrds released a single called 'Eight Miles High.' The song was weird, electric, experimental and overtly druggy, starting with the title. And it belonged to a just-emerging genre of music — psychedelic — which within a year would turn on a generation. Many say 'Eight Miles High' was the first psychedelic rock song* (another contender, 'You're Gonna Miss Me' by Texas band The 13th Floor Elevators, was recorded later but released first).

Meanwhile, jazz had been enjoying a renaissance for a couple of decades, breaking out into the new genres like bebop, hard bop and free jazz. They were sometimes jaunty, sometimes moody, always sophisticated and increasingly experimental. The greatest jazz saxophonist, John Coltrane, became driven by spirituality, and absorbed influences including the sitar legend Ravi Shankar, a master of Indian classical music and its mood-inducing mode-based patterns of notes called ragas.

The music sank in deep, and provided the key to moving them on from jangly folk-rock.

Psychedelic and jazz were both free in spirit, both drew on different musical sources to chart new territory — but they may well have come from different planets. Psychedelic was rock'n'roll, white and electric, modern jazz was mainly the reserve of black virtuoso acoustic instrumentalists. As for Indian music, it was literally a world away. But they all came together in 'Eight Miles High'.

The Byrds came together in Los Angeles in 1964, inspired, like many American groups of the time, by the Beatles. Their name comes from changed spelling, just like the Beatles (it's not a reference to bebop trumpeter Donald Byrd). At first, the Byrds even dressed like them and had mop-top hair. But they made their name with covers of Bob Dylan songs, scoring hits by transforming his acoustic folk songs into jangly, electric pop, driven by Jim (later known as Roger) McGuinn's 12-string guitar and chiming vocal harmonies.

They toured England in August 1965. That was the subject of the lyrics that Byrds tambourine-player Gene Clark wrote for 'Eight Miles High' — the height of their flight there, but reaching 13km with two miles added to sound better. The 'rain gray town, known for its sound' was London, and 'sidewalk scenes and black limousines' was what they experienced — the fans, 'some laughing, some just shapeless forms', screamed from the streets Beatlemania-style as they were shepharded around in Austin Princess cars. The Beatles befriended them, but the British critics were cool, and an English combo, The Birds (Rolling Stone Ronnie Wood's first band), served a writ about the name. Clark's lyrics say of England, 'nowhere is there warmth to be found'.

The Byrds touch down at Heathrow in August 1965. From left: Gene Clark, Chris Hillman, Michael Clarke, Jim McGuinn, David Crosby, publicist Derek Taylor, and, notably, two possibly concupiscent stewardesses. (Keystone Pictures USA / Alamy)

Writing credits go to Clark, McGuinn and rhythm guitarist David Crosby. The unlikely musical connections start with Crosby. He'd been introduced to Coltrane and Ravi Shankar recordings by a record producer in Los Angeles in 1964 and was blown away. He got McGuinn hooked as well, and would later enthuse George Harrison about Shankar too. A few jazz musicians, including Coltrane, had discovered Shankar as early as the late 50s.

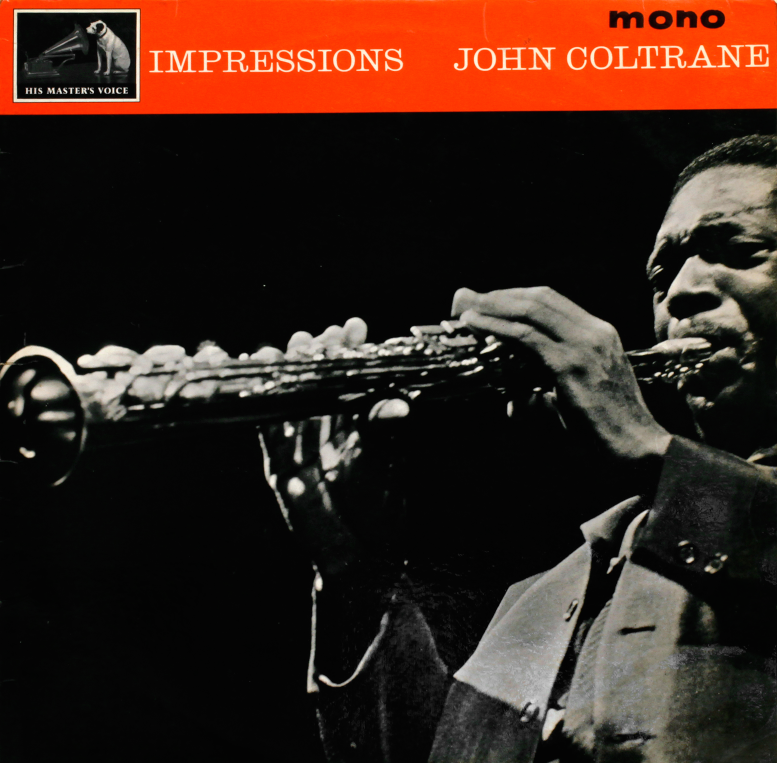

In November, The Byrds toured the USA, and what they listened to on the road in their Winnie-Bago was on cassette, a format invented by Philips and available since only a year in the US. (Crosby remembers 'reel-to-reel', but memories blur and cassettes were reel-to-reel anyway, just miniaturised and encased). The Byrds had one tape — full of Shankar and Coltrane's album Impressions. The music sank in deep, and provided the key to moving them on from jangly folk-rock.

Ravi Shankar. Photo credit >

John Coltrane's album Impressions (released 1963 on RCA) included the track 'India'.

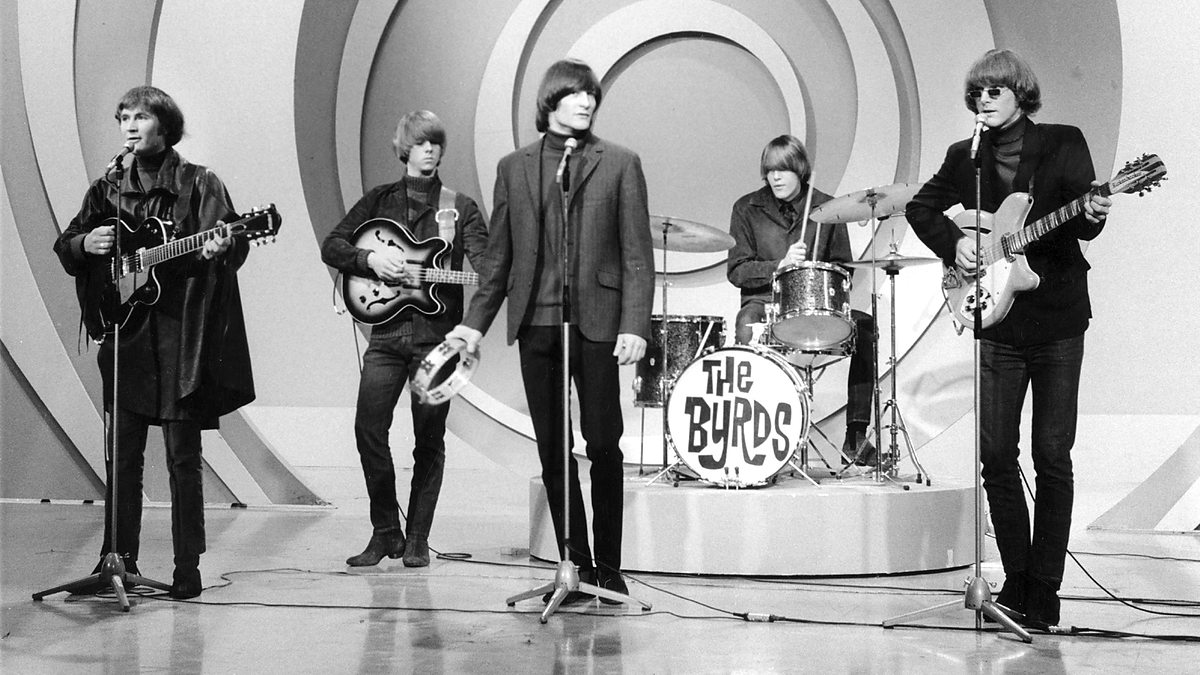

The Byrds recorded 'Eight Miles High' and the B-side, a Crosby-McGuinn composition called Why, at RCA Los Angeles in December 1965, but they had to re-record it the next month because their record label, Columbia, insisted it came from their own studio. With his 12-string, McGuinn emulates Coltrane's improvisational saxophone, particularly his 1962 recording of India, a jazz evocation of Indian music. The vocals, all in harmony, drone under the influence of Indian sounds, and bassist Michael Clarke and drummer Michael Clarke lay an insistant, ominous continuum to the sound. It was released in March and was widely banned because of its drug references, but it still charted. Why may sound more conventional than 'Eight Miles High', but it, too, was heavily Indian influenced, and is also considered one of the Byrds' best. There's a TV studio film which superimposes astronomical images on the band and underlines the darkness of 'Eight Miles High' with shadowy lighting. It's as if it predicts how 'cosmic' would soon be a hippy buzzword. Gene Clark had already left the band because of a fear of flying, leaving just four Byrds. Crosby wearing a hat is the main subject of attention, miming his chunky rhythm guitar line.

The positions are closed and fervent, the tone divisive and dangerous.

Crosby would be fired from the band in 1967 and go on to greater fame in Crosby, Stills and Nash. The Byrds would go through various personnel changes and become country-rock, finally to dissolve after an original line-up re-union in 1973. The Beatles had already introduced the sitar into Norwegian Wood in 1965, and after Harrison became close with him, Shankar would reach Western popular audiences. Coltrane too had met Shakar, but died in 1967 before he could formerly study under him. After Coltrane's death, his wife Alice, a major jazz pianist who had been in his band, was guided by an Indian guru and established an ashram in California in the 70s. This century, Shankar's daughter, Norah Jones, has become a star of contemporary jazz, rock and country, while her younger half-sister Anoushka Shankar is a sitar virtuoso.

The Byrds in concert, 1965: David Crosby, Chris Hillman, Gene Clark, Michael Clark, Jim McGuinn. Photo credit >

Why does 'Eight Miles High' matter after half a century? Is it just cause for nostalgia, or retro-FOMO (the fear of missing out on something long gone)? Maybe, but the song is extraordinary in its own right. It pretty well defined the term 'far-out'. It stands as a highlight of perhaps the most creative year ever for electric-guitar based music. 1966 also saw the Beatles and Dylan release towering albums, Revolver and Blonde on Blonde, The Stones' scintillating single 'Satisfaction', and it ended with Hendrix's first single 'Hey Joe', an old song the Byrds had also covered.

But it also matters because we live in times when particular political and religious groupings are looking backward, demanding that their version of where their loyalty lies ('America', 'Britain', 'Islam' for example) become 'great' or 'pure' again. The positions are closed and fervent, the tone divisive and dangerous. When we look back at the 1960s, we see a time that, for all its faults, liberated mindsets. It nurtured a youth cultural revolution, it completely transformed music, art and fashion, and not at least mobilised US opinion to fight for civil rights and protest the Vietnam War. 'Eight Miles High' didn't address any big issues, but it reached out musically and it ushered in the psychedelic soundtrack that would lead into 1967's 'summer of love'.

We've slipped a long way back from that. We need to build not walls but bridges, and step down from entrenched positions. But perhaps, as Clark's lyrics say, '…. and when you touch down / You'll find that it's stranger than known'.

* The Year the Music Died: 1964-1972, by Dwight Rounds, (2007) Brisbane, Australia: Bridgeway Books. p. 59; and Die at the Right Time!: A Subjective Cultural History of the American Sixties, by Eric V. D. Luft. (2009), Baltimore: United Book Press. p. 155.

EIGHT MILES HIGH (Clark/Crosby/McGuinn)

Eight miles high and when you touch down

You'll find that it's stranger than known

Signs in the street that say where you're going

Are somewhere just being their own

Nowhere is there warmth to be found

Among those afraid of losing their ground

Rain gray town known for its sound

In places small faces unbound

Round the squares huddled in storms

Some laughing some just shapeless forms

Sidewalk scenes and black limousines

Some living, some standing alone

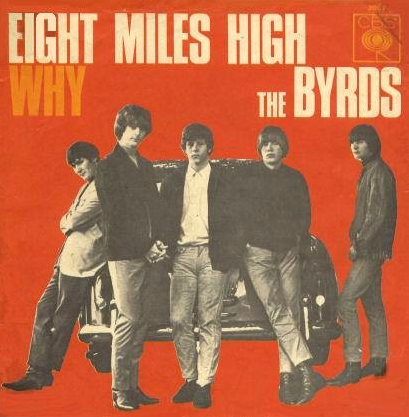

UK single sleeve for Eight Miles High. Note Austin A135 Princess as leaning object.

HERBERT WRIGHT is a London-based author and journalist specializing in architecture and art, and Editor-at-Large of The Journal of Wild Culture. He studied physics and astrophysics at the University of London. He is currently a contributing editor of Blueprint magazine, and contributor-at-large to Design Curial. www.herbertwright.co.uk

This article first appeared in these pages on August 8, 2016.

Comments

The Yardbirds' album "Roger…

The Yardbirds' album "Roger the Engineer" is considered by some to be the first album made specifically for the psychedelicized listener. what with the mental twists of "Over, Under, Sideways, Down", the haunting "Ever Since the World Began", and the bonkers trippy "Hothouse of Omagarashid", among other terrific mind benders. Great album.

Thanks, Michael, for this…

Thanks, Michael, for this good historical link to 'Eight Miles High.' It seems that the Yardbirds' work is becoming better and better understood, and appreciated, as a very key step in the development of British rock. Of course, this is especially due to the later influence of the three guitar wizards who were part of the band at different times (Clapton, Beck and Page), but it is also a product of the particular musical aesthetic this group of musicians were reaching for, and at a time when they were all charging ahead with no real idea, exactly, where they were going — other than that the work of elderly American blues artists was the bedrock they needed to be standing on. See this article for more on that ... https://www.musicradar.com/news/yardbirds-eric-clapton-jimmy-page-jeff-beck-10-reasons- — Whitney

Great article and backstory…

Great article and backstory. Thanks for this, Mr. Herbert Wright.

'Eight Miles High' is an amazing sonic universe, and often cited as the first psychedelic song. People sometimes choose 'You're Gonna Miss Me' by the 13th Floor Elevators for this distinction. But has anyone ever considered 'See My Friends' by the Kinks, recorded in May 1965 and released later in July? It's totally psychedelic and predates both by seven months. They're all great songs, but I haven't found anything trippy before 'See My Friends' in mid '65. Thoughts?

Add new comment