TORONTO — There was a bully in my first year of high school in Walkerton, Ontario who used to harass and insult me, especially after gym in the change room. He was kind of scrawny with beady eyes. At 13, he didn’t intimidate with size, only meanness.

The passage of time makes me think that he might have turned out well. He might have grown up to be good looking or accomplished, except that he died during the summer between grade 9 and grade 10. I remember that September, entering those terrazzo floored hallways lined with lockers, hearing the news and feeling happy. The bully was dead, killed in a car accident.

Some people were sad and spoke solemnly about his life that ended too soon. Not me. I didn’t say anything. This was for me a lesson that life, and especially death, was going to be much more complicated than most people were prepared to say.

In amongst all the unavoidable sorrow, the awkwardness, the plans upended and the inconvenient group excursions to the shores of eternity, there is also freedom in some form or other. If nothing else, it is the release from pain and suffering. No one who has watched someone die of a wasting disease can say they haven’t witnessed this. It is a much larger thing than any puny belief in Heaven.

THE SICK ROSE

O Rose thou art sick.

The invisible worm,

That flies in the night

In the howling storm:

Has found out the bed

Of crimson joy:

And his secret love

Does thy life destroy.

Then there is that perennial killer of young men, war. But even then, there can be a strange, horrible beauty as in Whitman’s dreamy 19th century poems from the American Civil War.

RECONCILIATION

“Word over all, beautiful as the sky,

Beautiful that war and all its deeds of carnage must in time be utterly lost,

That the hands of the sisters Death and Night incessantly softly wash again,

and ever again this soil’d world;

For my enemy is dead, a man divine as myself is dead,

I look where he lies white-faced and still in the coffin — I draw near,

Bend down and touch lightly with my lips the white face in the coffin.”

Ancient folklore has drawn a picture of the grim reaper, hooded, scythe in his boney hand, waiting to harvest us like so much grain. The popular culture of our own time has again become fascinated with death. Not since the middle ages, when dancing skeletons were painted on church walls and ceilings, has death become so entertaining.

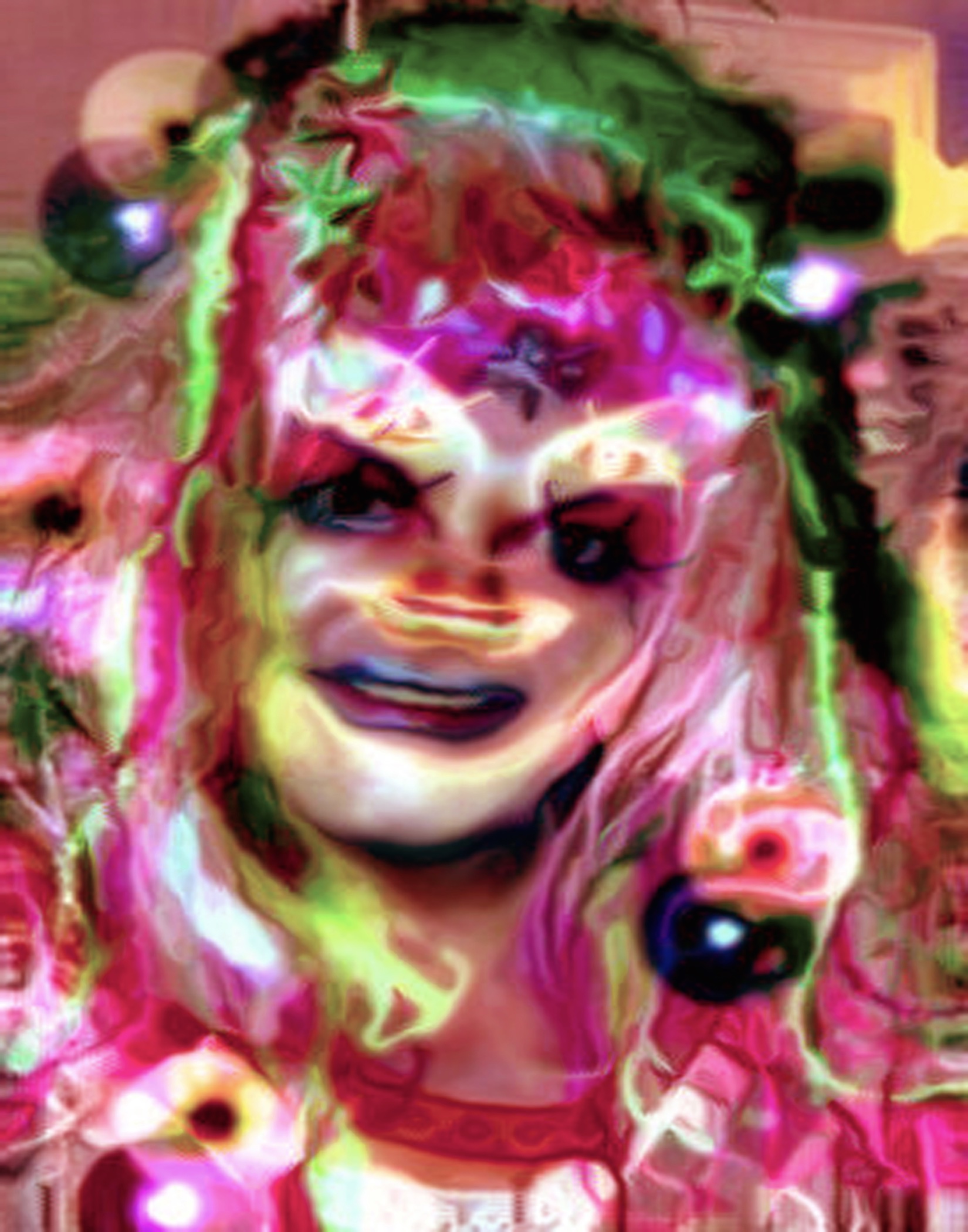

For Andrew Harwood, Death is a ghoulish drag queen in impossible heels. Personified by the performance artist Ivory Towers, with choreographic help from Keith Cole, Death does a coy little dance — in front of a screen of death-related pop culture images — before she picks one hapless victim at a time from an innocent and unsuspecting group, foolish enough to be there. Then she stares her victim directly in the face, nose to nose. Talk about awkward . . .

This performance happened on the opening night of his show, Phantome Aesthitique — Notes from the Funeral Camp, in January at the Paul Petro Contemporary Art in Toronto. The exhibition follows a natural progression of Andrew’s work: his performances as a psychic reader, Séancé, who is a medium; his drag bingo nights at the Drake Hotel; the “prairie style” show he brought here from his hometown, Winnipeg; and the glitter covered motorcycles he presented at the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art. Underneath all of these — and many other light-hearted, trés gay performances — there is always a lot of careful observation of human nature.

In all of Andrew's camp celebrations of low and pop culture, he talks about the things nobody wants to talk about. Whether it’s hobby crafting, psychics or growing up liking Anne Murray, these topics turn up in his work covered in glitter — as it is also when he turns his mascaraed gaze at death. He references Susan Sontag from her Notes on “Camp”: “Though I am speaking about sensibility only — and about a sensibility that, among other things, converts the serious into the frivolous — these are grave matters.”

The higher functioning parts of his brain didn’t have enough activity to indicate dreaming or hallucination.

The pun from that quote is not intended to cue the laugh track. As she also so brilliantly says in the Notes,

“It's embarrassing to be solemn and treatise-like about Camp. One runs the risk of having, oneself, produced a very inferior piece of Camp.”

The images on the screen behind dancing Death reflect Andrew’s growing interest in video, including the computer-generated music. They reveal that we do use death — everything from Halloween to vampires to zombies — as entertainment, and even child’s play. Images of recently departed celebrities and entertainers pop-up: Michael Jackson, Yves St. Laurent, Kurt Cobain.

In the gallery there are cylindrical lamps, reminiscent of a funeral parlour, made with these ghostly images. They not only connect to his love of low-culture crafting, but they also make sure you understand this is not callous mockery, this is not satire. In truth, this is camp. Camp being to satire what The Colbert Report is to The Daily Show — with Stephen Colbert in his Brooks Brothers pinstriped suit and steel rimmed glasses in hetero-Republican drag. All of his over-the-top imagery and style meets Sontag’s attributes of camp exactly. Our expanding love of camp may be out-growing her Notes; her death came in 2004, 40 years after she wrote them.

Like our fascination with camp, our love of death has become a bit of a phenomenon. Vampires have been a genre for awhile now, people participate in zombie walks, psychics and ghost hunters are TLC fare, and Halloween has become a month long celebration of tombstones and skeletons. And our displays of mourning are starting to rival the Victorians — who can forget the thrown flowers that covered Diana’s hearse? As the growing trend towards cremation has mostly removed the corpse from funerals, audio-visual displays at memorials have become a replacement.

They get accustomed to other people’s deaths, but they certainly don’t get accustomed to the idea that they will die.

And it's not surprising. Religion has so little to offer anyone anymore with regards to dying. If enough people believe in psychics and ghosts to make mainstream TV shows, fewer and fewer people are willing to say they anticipate life after death, even if that is what they are hoping for. But without that hope, death always seems like a defeat. Handel’s grand oratorio and confession of faith, “Messiah”, trumpets “O grave where is thy victory, Death where is thy sting?”

Perhaps it’s that sense of defeat that keeps the scientific mind from wanting to think about anything after death. Eben Alexander, a practicing neurosurgeon who, among other things, taught at the Harvard Medical School, wrote a detailed account of his own dying and coming back experience. The book, Proof of Heaven, was on the New York Times bestseller list for 97 weeks. He later said that reading his charts afterwards. of his week in a coma, proved that the higher functioning parts of his brain didn’t have enough activity to indicate dreaming or hallucination. He also recounts implausibly flying on the wing of a butterfly, and visits a place he called 'the core'. Far from being filled with light, this place that could be considered his meeting with the Creator, was dark and shiny.

Still, his sceptics claimed that by ruling out any natural explanation, Alexander was not just unscientific, but anti-science. To bolster their argument, critics pointed out failings in his personal and professional life. For the scientific mind, any hope of victory over the grave must not only be denied, but also ridiculed. Take that, Handel.

Religion, now so out-moded, enemic and medieval, does little to make our contemporary mind look at death. For science, there is no ghost in the machine. We die and that’s that. So, who else do we have to turn to to make us consider our own deaths if not artists like Andrew Harwood? It’s not as though our modernity has erased our fear of and interest in death. It’s quite the opposite.

The Nobel prize winning Yiddish writer Issac Bashevis Singer wrote stories filled with taboo sexuality, ghosts and goblins. In one, Hitler and his fellow Nazis meet to talk in the same post-war, New York cafeterias that Holocaust survivors frequented. In his book “Séance and Other Stories”, souls line up in Heaven waiting for bodies to inhabit. Interviewed quite near his own death, Singer said,

“No one gets accustomed to death. For instance, the owner of a funeral parlour — you might think that such a man is hardened enough to get accustomed to death. No. They get accustomed to other people’s deaths, but they certainly don’t get accustomed to the idea that they will die. This is true about every human being. The fear of death exists in every human being from childhood to the grave. The only time when people stop being afraid of death is when they die.”

GENE THRENDYLE is a professional gardener who has been planning, building and maintaining private and public gardens in Toronto for more than two decades. He was a participant, consultant and in charge of maintaining the Artists’ Gardens at Harbourfront from 1998-2008. Gene is also an artist who has been involved in the arts in Toronto for over 25 years. Since 1989 he has been featured in solo or group shows around the world.

IMAGES: From Andrew Harwood's "Diva Series", used with permission by the artist, courtesy of Paul Petro Contemporary Art.

Add new comment