This is a tough time for photography purists. Since the discovery in the early 1700s of light-sensitive silver particles that reproduced an image of something in the world, the definition of what a photograph ought to be, or ought not to be, has been batted around endlessly.

The traditional notion of what quality photography regarded as art is — as practiced by, for instance, Ansel Adams in landscape photography, Richard Avedon in portraiture, Diane Arbus in street photography and Dorothea Lange in documentary photo journalism — assumed the supreme goal of finding what Cartier-Bresson called 'the decisive moment’ in a single, ‘caught’, actual event. Today, in the post-smart phone, post-Photoshop world, what we mean by a photographer and a photograph is less and less clear. The optics are ever shifting.

For example, the £30,000 Deutsche Börse Foundation Photography Prize — described in The Art Newspaper as the biggest and most prestigious photography prize in Europe — has eligibility criteria that increasingly “expands the limits of what photography is, what it can do, and who can be nominated.” True to such expansionism, this year’s winning entry was not a photograph at all, but a film installation. Another competition, Lens Culture's Art Photography Awards, states that it is "open to considering all types of photographic art — everything from printed art on gallery walls to sculptural objects, experimental processes, and totally new forms and formats." Really? You've lost me. Maybe we're looking at it through the wrong frame. Maybe the word is the thing . . . and that the term 'photographic art', rather than photography, more accurately describes what is going on in the field of artistic expression using photographic technology.

Karl Schiffman, whose photographs are the subject of this essay, reported an experience relating to this question. “I watched a video online from a recent Art Basel," he told me. “It was a session about ‘new photography'. All the panelists were very interesting but struggled to say anything interesting about where art photography was going, or should go. Yet they all made the point that young photographers refuse to call themselves photographers and prefer the term 'artists'.” Though he eschews categorical terms and sees "art as a craft for blurring or erasing them", for himself Schiffman prefers 'photographic artist.'

He evolved his own term 'aura,' the 'here and now' of an art object and its unique existence in space and time, which defines its authenticity.

About a year ago I saw a handful of photographs of Schiffman's that caught my eye. They were compelling single images but they also seemed to be part of a body of work governed by a coherent approach to photography in general. I didn’t know what that approach was, but, month by month, as he showed me his new pictures, I was impressed at how he was attacking the question of what, he says, "makes a challenging photo and why. But more accurately, the photo itself, not the subject matter. A photo of a giraffe cleaning a high window is 'surprising' . . . but not necessarily photographically surprising."

As a restless sort of serious and grounded person, Karl Schiffman's creative energy translates simultaneously into focused productivity and dispersion — a common cocktail for artists. For instance, he has concurrently been working with three different types of photographic presentation: a single ‘caught’ image of an actual event; the diptych: two images presented side by side; and the photo collage: invisibly melding two or more images together to suggest a single, captured-in-the-moment photograph. That is, in addition to skulking around in the tradition of great street photographers — sleuths coolly on the lookout for, in Cartier-Bresson’s words, the image that ‘offers itself up’ — Schiffman is experimenting with two examples of photographic hybridism.

His path to his current artistic work has been a peripatetic one. In the 1970s Schiffman traveled from his native Australia to Canada where he earned a PhD in psychophysiology at the University of Toronto — the physiology of psychological processes and perception. “For some reason, almost immediately”, he says, he decided to go to India to make a film on the Ganges River, which was eventually funded by National Geographic; other documentaries followed until he wrote a screenplay for Warner Brothers studios and became a screenwriter and script doctor in Los Angeles, Australia and London. Along the way, because he wanted to do with words what seemed best done in song, he wrote and recorded an album; some of the songs have been licensed to TV series. These days Schiffman spends his time equally between Toronto, San Miguel de Allende in Mexico, and Berlin. Less than two years ago he took up photography seriously “to try to understand photography in a post-cell phone, post-Photoshop world … where technical advances were the photography equivalent of the invention of something even ‘better than steroids’ in sport. Anyone could be almost Lance Armstrong in photography.”

Before I discuss in more detail how Schiffman is contributing as a productive explorer of single 'caught' image photography, I want to look at the diptych and the photo-collage — and how, in my view, they are interdisciplinary, sub-station art forms that stand on the out-pastures of photography. I do this not to go into generalized theoretical territory for its own sake, but to better understand the overall assault that Schiffman is waging with his experiments.

What is a photo-collage and why should we want to know when we’re looking at one?

Based on what we had come to expect through our experience looking at images, a sort of contract used to exist between the viewer and the photographer that assumes that a photograph is presenting a document of a real, non-fiction occurrence in the world, evidence of actual space and time, not a fabrication. The viewer came to a photograph, ready to be affected, with the assumption of trust. Such an assumption is not unlike what we come with when we attend an exhibition by a photojournalist: we expect photographs of things that really happened rather than scenes that have been staged, as in a feature film, that are facsimiles of reality. Or, like journalists who publish a fake story, their delinquency affects our overall confidence in the act of consuming news.

But nowadays in art photography, all bets are off.

As I push my foot to the floor of this covenant on realism between photographer and viewer, I am reminded, by those better informed than I, that this train left a long time ago; and, that we have no way of knowing the verity of a photo any more. Schiffman agrees. "In the pure sense of the concept," he says, "nothing is a 'single caught image' any more. That is so binary.” Fine then . . . old-school, distinction-granny binarist am I! Nevertheless, I'm on the train that’s left the station and I'm talking to a whole car full of others here (including you, maybe) who still want to know: does one thing end where another begins, or is it all une mélange moderne?

I want to work with the sceptical eye of today’s viewer, not deceive.

In the above photograph, ‘Piano 2 Chair', which is two photographs fused to appear as if they are one — unless we are told that this is a photo collage we assume that we are looking at an actual event, when in fact we are looking at two different places and two different times. Schiffman says he has made the manipulation obvious to the viewer; not so for me. If a photo collage is not plainly presented or labeled as a construction of manipulated elements, but seeks to disguise itself as a caught moment, then there is a breach of contract with the viewer.

The critic Walter Benjamin evolved his own term "aura," the "here and now" of an art object and its unique existence in space and time, which defines its authenticity.’1 If the innocent trust that comes from the viewer’s open mind and willingness to be touched by a photograph’s ‘aura’, if this trust turns into suspicion that the viewer's innate knowledge of the world, as it is, is being ‘played’, then photography as we know it is in trouble. Like all broken social contracts, photo collage disguised as realism puts cracks in the vessel of human intuition. And as we know, when we are lied to, our intuition is damaged.

Schiffman has a more sanguine view. “Apart from a few highly responsible documentary photography fields," he says, "photography has joined the rest of our post-Truth World. That’s just fine. Art is a lie that points at the truth. When I join images together, I’m not trying to do it so seamlessly that the manipulation may pass the sceptical eye of today’s viewer. I want the manipulation and the image collusion to be seen — but only after a couple of silent beats and a slight delay. I want to work with the sceptical eye of today’s viewer, not deceive. My photo manipulations are themselves a comment on manipulation and hold the manipulator fully responsible for the outcome.”

'Pink.'

Perhaps the centre margin in ‘Piano 2 Chair’ between the two chairs eventually tells me that, “after a couple of beats”, this is a constructed image. I’m not convinced. It seems like a lot to ask the viewer, and at the least might tax their optic hospitality for concentrated perception. Schiffman’s explanation seems equally constructed, which is fine: the path of an artist’s curiosity is always interesting, even if it loses out to the ‘voice’ of the work. Whether I notice the manipulation or not, for me the aggregate images of Schiffman’s lack the singular power of his unmanipulated images, of which I speak more of later. They are not stirred by the eddy of his core talent.

The drawing of borders and making distinctions between one way of doing art and another is similar to how, in cinema, the Dogme 95 collective created a manifesto with rules for how a film could be made: with traditional values of story, acting, and theme, hand-held cameras, location sound only, no post-production special effects or music. Dogme 95 was a manifesto about artistic provenance. MIght art photography benefit from a similar kind of unwritten customary agreement that guides how manipulated single 'caught event' images are presented in galleries or when published, as paintings in an exhibition declare what medium they were made with — oil on canvas, acrylic on masonite, crayon on paper partially eaten by dog.

Incidentally, this emphasis on photography’s incursion by photo collage has no bearing on the power of a technique that uses Photoshop and other programs to tease out everything that great art is capable of delivering — as can be seen in the work in these pages by a masterful hybridist, graphic artist Ric Simon.

Two Images Hinged Together

The diptych, two images presented side by side, has none of the trickster capabilities that photo collage does; with diptych it is clear what we are looking at: two different places, two different times. Photographic diptychs have a playful and reverberant charm — the juxtaposed image content of the two images resounding with or against each other — but the practice takes us out of photography and into the act of image making or art making.

But in terms of our subject here, which is Schiffman’s goal to understand for himself what photography is, using his photographs to produce diptychs dilutes the energy and gravitas of his quest, which he harnesses efficiently with the single, caught-in-the-moment image. In 'Pink', though the bi-play between the two images does a delicate and curious dance, the quality of the image on the right is something I’d rather step into alone — solo, sotto voce — to allow its warm, tidy and whimsical space to envelope me as I wait for someone to come through the door on the right. I suppose, for Schiffman, it is a matter of not having the confidence in the aura of the pink room on its own, or, rather than leave the one image to stand on its own, there is again the restless urge to experiment further.

'Waiting for a Miracle.'

The Single ‘Caught’ WTF! Image

Now we come to the area of Schiffman’s work that, in my view, if he continues as he is, will become his trademark style and where his influence will be most keenly felt: the single ‘caught’ image. Whether there is some Photoshop tinkering or not, having seen an assortment of his photo collages, they do not speak with the same mystifying authority that these ‘in-the-camera’ shots do. For me, each of the seven photographs presented below suggest the productive psychic bewilderment that stirs in our minds at night. Schiffman’s single ‘caught’ images appear, at their best, to be made from the rebel emotions that fly aimlessly around . . . then quickly converge into pictures we collect in dreams. “Photography is like the art of another planet," wrote Henri Focillon in The Life of Forms. For Schiffman, photography is another level of self-consciousness: a strong photograph by him grabs our attention like a poster for an upcoming lucid dream.

‘Waiting for a Miracle’ has the quality of a processed, played-with image but is in fact not one. A group of city dwellers seem to be waiting to be picked up from work to go home, or whatever location is the end of labour and the beginning of relief, at least until tomorrow. The porous, monochromatic light-silhouette bodies rain inside a silent ensemble of loners — strangers to each other but tied by some random purpose. A queue of mistake-makers in purgatory, taking stock, reviewing lies, excuses and reasons, rehearsing their explanations.

'Motel 2 White.'

In ‘Motel 2 White’, a muscular figure is hanging, and hanging on, suspended from the railing of a whitewashed building we're told is a motel but no motel we've ever seen! And what is he doing? This is another of Schiffman’s WTF! photos where we look, and, without taking our eyes off it, look again. The delayed reaction to something unexpected is what the photographic artist is going for: the power of an image that, like a fantasy trope, won’t let go of our gaze.

'Glass Darkly.'

‘Glass Darkly’ is an ordinary enough content, an overrun, lush-green backyard with a dilapidated soccer net seen through a glass tumbler with a bullet hole in it; well, maybe a bullet hole. That's the thing. We know what we’re looking at here, but then maybe not. The rush of blurry light suggests a secret space from which to be securely shy about the world.

’Mannequin Gaze’.

In ’Mannequin Gaze’, the presence of a shiny-faced child’s doll in the foreground, the paint over the curls on its head worn thin, modulates the camera’s ogling view of an athletic woman bending down, her back to us in a safe, private moment of self-ministration.

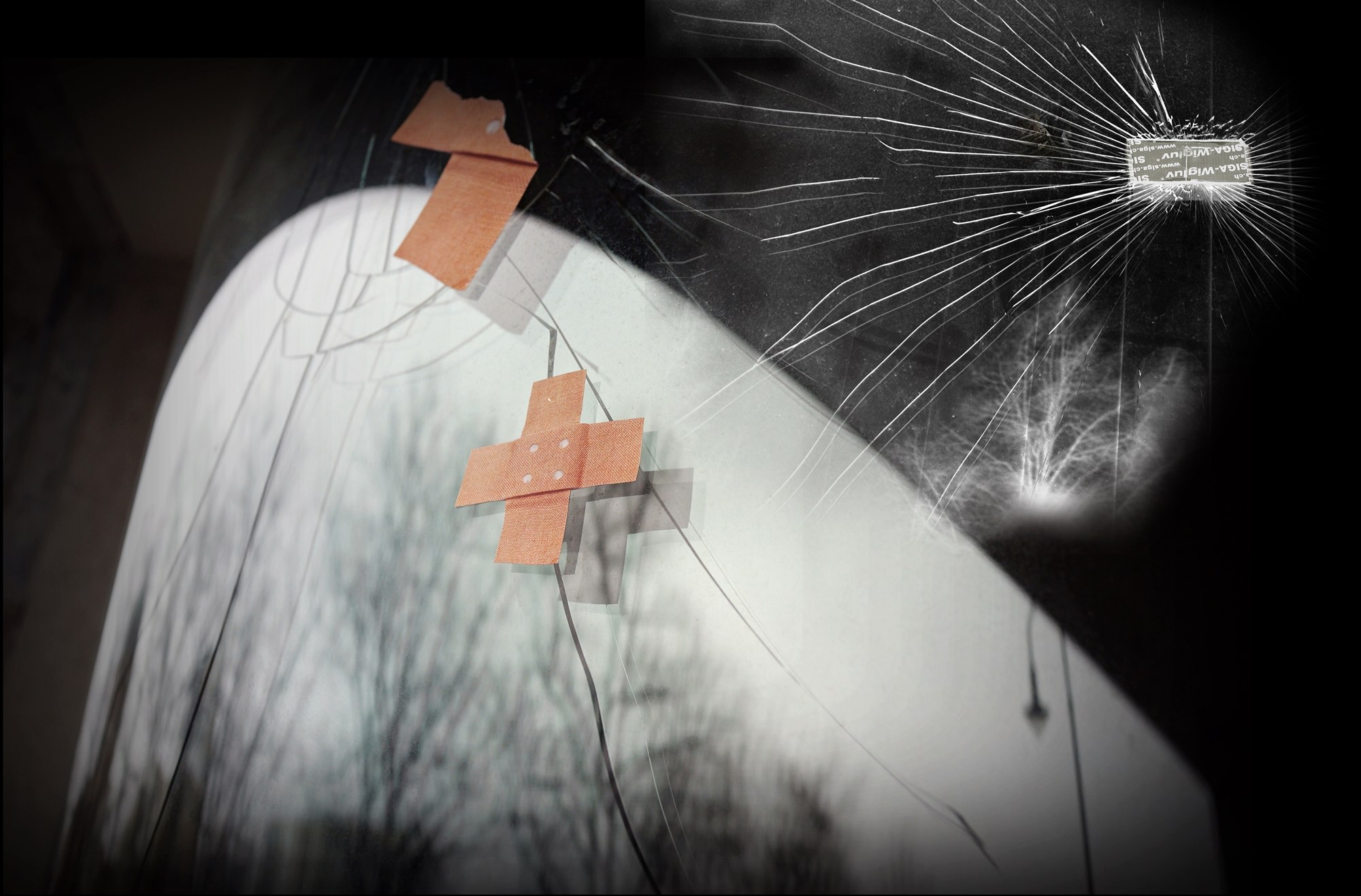

'Band-Aid'.

'Band-Aid' could be a still from an Ingmar Bergman film — tortured cracks in glass that spread out like sparks from a fireworks wheel in a dark sky. A shadowy, winter forest invites avoidance. Two adhesive bandages, one torn and one cleanly marking a cross, dress the window. Again, the subliminal rumblings in some of Schiffman’s pictures deliver to the viewer a Rorschach test of possibilities.

'Psychokinesis'.

‘Psychokinesis’ presents a delightful and colourful balancing act between banality and vigour. While a red ball sits frozen in motion in the air above the felt plane of a billiard table, random guests at a stillborn event in the background weigh the burden of patience and boredom — hungry, symbiotic areas of action vying for notice.

"Look at me!"

"No, me!"

It is a good example of what Schiffman describes as his main goal in taking photographs. “I strive to inject into my pictures multiple centers of interest that compete for the viewer’s discretionary attention — almost in the way companies compete for the consumer’s discretionary income. These various centers of interests are approached by the viewer, in a different order and different way, and then combined by the viewer to create meaning in the picture.”

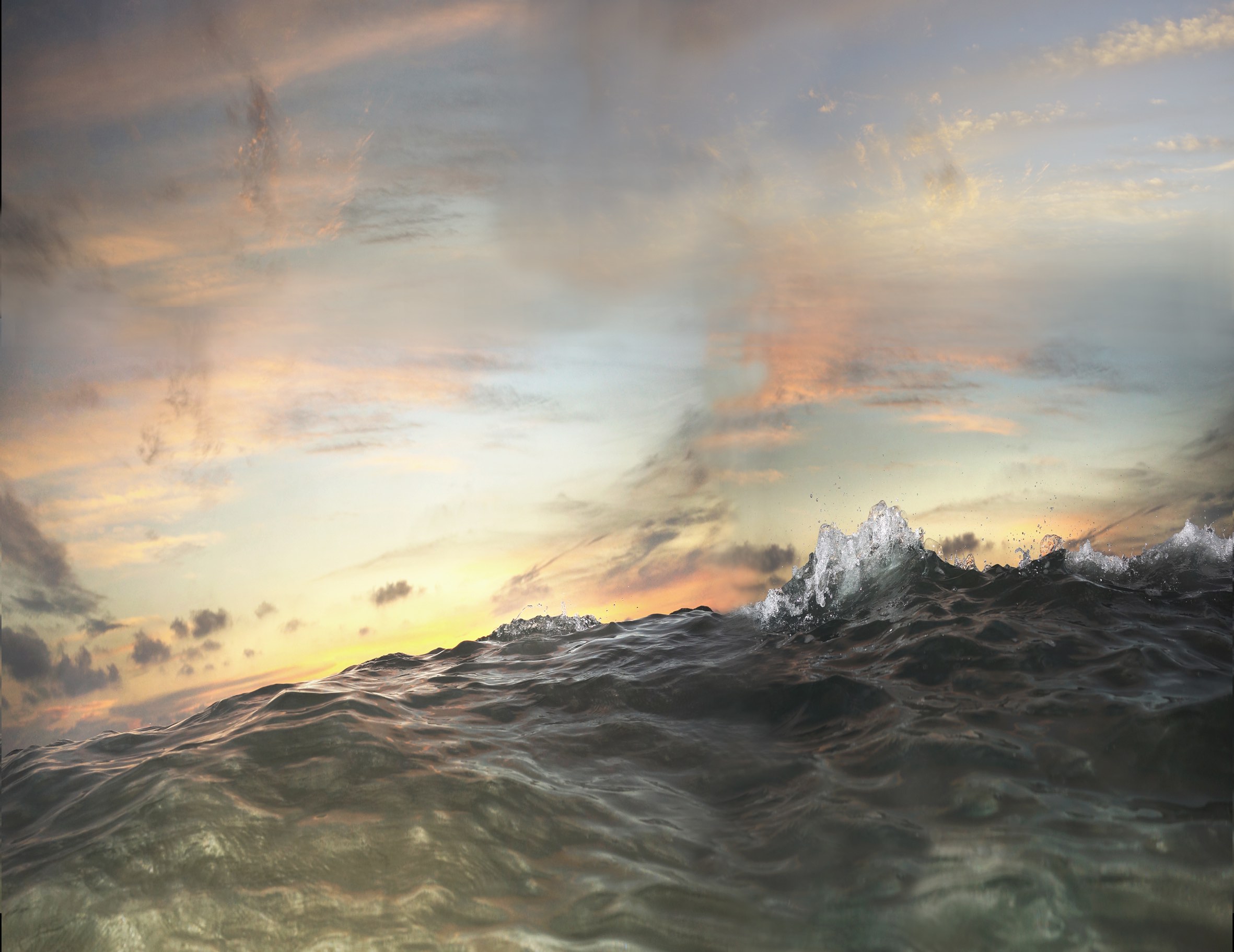

'Castles’ places us in the centre of a miniature storm at sea. It is a remarkable view of a mountainous liquid form up close, an instant congealed, possibly before our last gasp. A sunset touched with gray cloud wisps is a final glimpse of the pretty world.

‘Windowless in Berlin’, below, is the backside view of a row of old and ordinary (yet ironically majestic) brick buildings anointed with graffiti; marked by culture that roves. As if simmering in morning light, the street structures appear to be levitating over a pan of clouds. Here is what media theorist W. J. T. Mitchell called a "magical relation." “When students scoff," wrote Mitchell, "at the idea of a magical relation between a picture and what it represents, ask them to take a photograph of their mother and cut out the eyes.”

These buildings seem to have their own faces and expressions within the embracing frame of the parental light and mist above and around.

'Windowless in Berlin.'

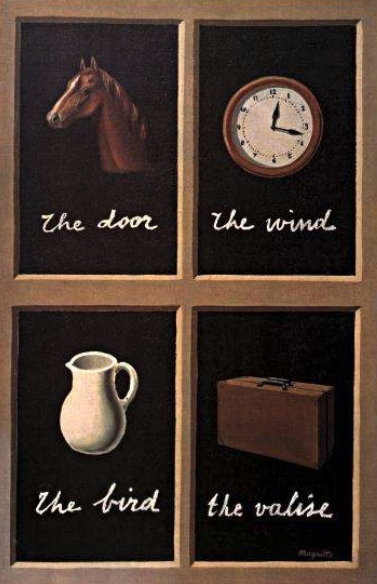

In his book Ways of Seeing, John Berger writes: "The relation between what we see and what we know is never settled. Each evening we see the sun set. We know that the earth is turning away from it. Yet the knowledge, the explanation, never quite fits the sight. The Surrealist painter Magritte commented on this always-present gap between words and seeing in a painting called 'The Key of Dreams' . . ."

Berger continues: ". . . The way we see things is affected by what we know and what we believe."

Karl Schiffman's pictures are visual poems of perceptual mystification borne of a belief that something unknown lays waiting to be discovered. Art photography exposed to technological temptations may be all over the place, for good or ill, but it will never be resistant to the inoculation of a potent talent. “No amount of technology,” writes Irish photography critic Sean O’Hagan, “will turn a mediocre photographer into a great one. Nor, in conceptual terms, will it transform a bad idea into a good one. For that you would still need to possess a rare set of creative gifts that are still to do with seeing, with deep looking.”

I expect Schiffman will continue his experiments with photographic alchemies of various sorts, and for important reasons: they will keep him looking around on the periphery, where the action is, for what is at the centre of his quest. But his real lab is out in the city, stalking, “The picture is good or not," said Cartier-Bresson, "from the moment it was caught in the camera.”

Some might leave the deft manipulations to others less quick on their feet. Some might float quietly around, look for magical relations, keep the trigger finger ready. Fortunately, these are things Schiffman seems not to rebuff. "The 'voice' whispers to you as an image crosses your retina," he says, "and you move on. The voice nags that this 'nothing' image has something rattling about inside it. You listen and go back to take the picture. Three weeks later you look at the photo and see what the voice was talking about."

CODICIL

All sorts of voices of the past echo along the path where something new and truly original might be found. The following voice, the voice of an artist who knew so well how such a path could to be regarded, gets the last word. It is the voice of René Magritte, from Propos de René Magritte recueillis par Maurice Rapin, leaflet of the Tendance Populaire Surréaliste, 22nd Jan. 1958.

There is a familiar feeling of mystery, experienced in relation to things that are customarily labelled "mysterious", but the supreme feeling is the "unfamiliar" feeling of mystery, experienced in relation to things that it is customary to "consider natural", familiar (our own thought among other things). We must reconsider the idea that a "marvellous" world manifests itself in the "usual" world which asserts itself by means of coincidences: they make sure we recognize it more distinctly. Instead of being astonished by the superfluous existence of another world, it is our one world, where coincidences surprise us, that we must not lose sight of." ũ

WHITNEY SMITH is the Publisher/Editor of The Journal of Wild Culture.

Karl Schiffman's website.

Comments

A superb look at an

A superb look at an innovative artist, whose haunting images conjure a mystical view of the "everyday" world around us. Thanks for this generous introduction to, and appraisal of, Karl Schiffman's work. The admonitions of Cartier-Bresson and especially Magritte — that the marvelous surrounds us at every moment — give us aesthetic as well as spiritual reasons to be here now.

Whitney writes: "if a photo

Whitney writes: "If a photo collage is . . . not labeled as a construction . . . but seeks to disguise itself as a caught moment . . . there is a breach of contract with the viewer.” The only 'contract' I remember making with the viewer is an obligation to be interesting. This 'contract with the audience' idea flies better when discussing whether an artist violated the rules of his own work, rules created inside the work, such as in a film: if the zombies are set up as being 'unkillable' but then get killed. But I understand that my able profiler is not alone in his desire to know 'what' he is looking at. Others with his POV might desire to know if elements of a novel 'really happened' to the author. ¶ I also share some of those desires when I look at an image. But I'm eager to do the work to figure it out if there are clues planted inside the image that make the interaction rewarding. And it is this 'interaction between image and viewer' that I want to maximize. Whitney discusses my image: ‘Piano 2 Chair’ in this light. Lens-based art, unlike painting, must at some point deal with the physics of what a lens can focus on. A single lens cannot focus differently on the same plane of an image. Yet the piano is in sharp focus . . . which drifts out of focus as it reaches the plane of the piano chair but somehow comes back into focus along the same plane for the other chair. Clearly two images. And the clues are written inside the image with the photography vocabulary of focus.

Rather than ‘the contract to

Rather than ‘the contract to be interesting’, the only contract the photographer or artist displaying his or her work has with the viewer — at least in the well-established tradition of labeling what medium the work was created with (i.e., “oil painting on canvas” or “chalk on paper”) — is to share with the viewer, in the labeling, how the work was created. This is an act of social etiquette in the aesthetic conversation between creator and consumer. If we as an art-consuming audience want to throw out this tradition, then so be it; but until it is abandoned we are left with an expectation: that an exhibition of photographs presents work in the tradition of single capture photographs rather than photographic fictions, such as photographic collages. If it is, in fact, a collage, then merely label it such — ‘Photo collage.’ — so as to prevent our art viewing descend into a guessing game looking for clues to know how or in what medium it was created. And finally, if a new school of anti-labeling within the visual art and art photography exhibition tradition is to occur, then the declaration of that — perhaps in the introduction to the exhibition — would be further courtesy the viewer could receive from the artist.

Add new comment