Here we gif you the photo credit.

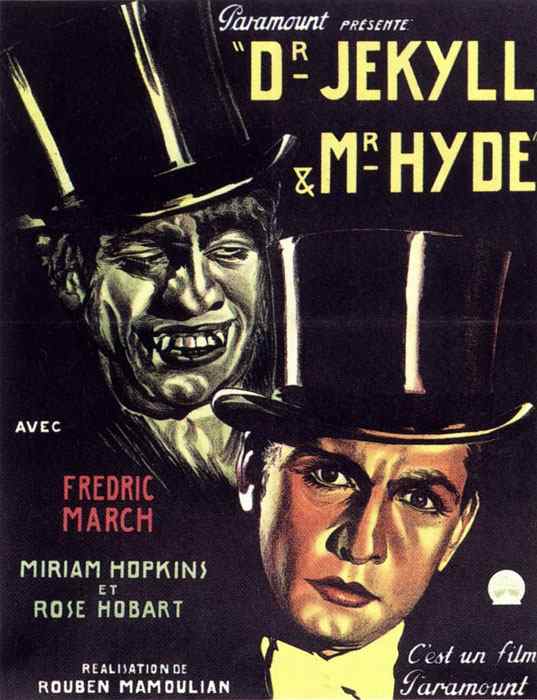

There have been many filmed Jekyll and Hydes, but this one—despite my fondness for the silent John Barrymore version from 1920—is my favourite: the 1931 version with Fredric March as Jekyll/Hyde, directed by the great Rouben Mamoulian.

Robert Louis Stevenson’s famous tale from 1886 is, as everybody knows, about a Victorian doctor’s dangerous success in making literal, palpable, the twin armatures upon which our beings are wound—armatures that are home to the eternal dichotomies of good and evil, angel and animal, superego and id, day and night, height and depth, life and death.

But not the least satisfying of Stevenson’s decisions in structuring his story is his happily providing a second set of dichotomies beyond Jekyll’s own interior division into good and evil, virtuous and monstrous—which is to say his providing an external female counterpart to the bifurcated Jekyll.

The creature’s wild simian look eventually showed up in the nether world of comic books and pulp horror magazine.

There are two women in Dr. Jekyll’s life: his faithful and supportive fiancée, Muriel (Rose Hobart), and the beautiful bar singer, Ivy Pearson (the wonderful Miriam Hopkins), with whom he inadvertently strikes up a sexually charged but obviously inappropriate dalliance.

This good-girl/bad girl doubleness, this echoing of the one woman’s civilizing power against the other woman’s corrosive erotic force is an absolutely conventional pairing all through 19th century literature. It involved the tensions between the woman identified as “The Angel in the House” (the phrase is the title of a popular work from 1854 by Victorian poet Coventry Patmore) and her distaff Other, manifested as the “Harlot in the Street.” Traditionally, the Good Woman (the “Angel”) was a blonde, while the unmoored, domestically untethered, dangerous non-wife of the public world was a dramatic brunette (flashing eyes, tossing hair). This doubleness—you find lots of it in Thomas Hardy—runs right up until, oh, maybe World War II. The last gasp of it is found in the 1939 film of Gone with the Wind, where the benign angel in the house is Melanie Hamilton (Olivia de Havilland) and the volatile, sexualized, dark-haired (red-haired will do as an emblem of danger), fireball-heroine is of course Scarlett O’Hara (Vivien Leigh).

I love the 1931 Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, but there’s one thing about the film that bothers me every time I watch it. It’s Mr, Hyde’s goofy appearance—more funny than menacing. I admire the technical machinations whereby the colours of Fredric March’s makeup were modified and amplified by the use of coloured filters (the film is of course in black and white) and all that ingenious stuff, but I can never get past a certain restiveness about Wally Westmore’s Hyde-makeup—no matter how influential the creature’s wild simian look eventually became in the nether world of comic books and pulp horror magazines.

To me, Mr Hyde looks like Jerry Lewis as the Nutty Professor. This is not Wally Westmore’s fault, since the Hyde makeup predates Jerry Lewis by thirty years, but I still can’t get past it. ≈©

GARY MICHAEL DAULT is a writer and critic who has been published in many periodicals since the 1970s. He is also a painter, teacher and blogger who has left the city to live in a small town on Lake Ontario between Toronto and Montreal. garymichaeldault.com

This article was first published in The Journal of Wild Culture, December 8, 2013.

Comments

Thanks for pointing out that

Thanks for pointing out that Hyde had a girlfiend, as well as Jekyll: I had forgotten that. What has always struck me and which must be on purpose is how the name Jekyll seems more appropriate for the villainous half of the person, but belongs to the good doctor.

Gaslight (Ingrid Bergman, Charles Boyer) would make a good subject here, though the dichotomy is different. And almost any Hitchcock film.

So glad to hear someone say

So glad to hear someone say that — about the names Jekyll and Hyde. Jekyll is so downright evil sounding for the decent physician, a cross between heckle and jackal, neither are cosy words; Hyde is normal enough but still cloaking something below a tough surface of skin. Of course it is more interesting that he did not hit the names on the button with their type. I wonder if there is any record of Stevenson being asked about the name question, or if he commented on it in his letters. Surely someone would have mentioned it. I'm going to have a browse and see if I can find something and if I do I'll get back to you, Naiad.

Add new comment